While I sought out a form, I encountered an archive. Ali Mirdrekvandi’s unpublished writings and related correspondences, held in the Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford.1 I had accidentally stumbled upon this archive, initially viewing it as a curious distraction. However, each time I thought more about it, visited it, spent time with the material, I felt a stronger pull. A sense of wonder and discovery gave way to duty and responsibility-towards: Ali’s story as an intimate snapshot of imperial relationality and subaltern survivance, a real-life parable of “victory in defeat.” I felt an urgency to relate to the archive, both as an “ancestral imperative”2 and as a geopolitical position.

What confused me was how “archive fever” had crept up upon me, the sudden instinct to speak-for, to say the historical, to “make it right.” I had been studying Ariella Aisha Azoulay’s work3 and trying to make sense of its polemics for my own relationship with the archive. Why was I falling under the spell of the new, tempted by possession, fetishizing the document? My initial ideas for the film flirted with documentary, its “objective” task of instructing informatively, while intuitively grasping that I had to situate myself, the primacy of my contemporary desires, as a ground for the project.

I spoke frequently of Ali in my psychoanalysis sessions, often associating him with feelings towards my parents, childhood memories of Iran, and the unresolved presence of religion, or rather, the wish to believe-in, persistent within my structure of desire. With time, it became clear that it’s never been about Ali. He is a portal, a convergence of significations and loose associations that allows me to access and bundle together scattered fragments of my inner world. My desire is contradictory: a melancholic ego suffering a loss, whose object cannot be properly named, re-attaches itself onto materials, surroundings, and encounters that stimulate a sudden, temporary, narcissistic rush of pleasure. Is a flash of remembrance at work here, Benjamin’s fleeting image of now-time? I was realizing that Ali had become an invitation to enjoy my symptom. I repeated a mantra to myself: the curse of the archive is the gift of the repertoire.

I met a scholar who had worked on the archive ten years ago.4 For her, too, it was an untimely accident and, in the end, a deeply generative failure. She had written two different novels in response to the archival encounter, neither satisfactory enough to publish for different reasons. One was too “in the head,” paralyzed by academicism; the other too personal and dreamlike, quite possibly inaccessible.

I was meeting regularly with a dancer to play in the land.5 There was something about our movement together and the site we had chosen that made me fantasize about Ali, as if this encounter could translate him into our bodies. Our gestures of carrying, holding, gathering, memorializing, mourning, becoming-animal, becoming-wild, yearning for the ground, struggling, striving, enjoying, our unexpected intimacy within a circle of trees alongside the railroad.

I started to make a division in my head between the dancer and the scholar that turned into a structure for the film. It would be two parts, one more concrete, the other more abstract. In this way I felt I could both represent and go beyond “something about an encounter,” to move in between the lines of the archive and eventually (hopefully?) leave it. Something felt wrong here. There were artificial separations between mind and body, document and gesture, history and myth, actor and witness. The curse of the archive was at work again. I had been ignoring the gift of the repertoire, its secret command to boldly embrace play, to let go, to find ceremony.6

I had cast the scholar and the dancer into roles that ignored and denied their desires, how these necessarily differed from my own, and how that difference is what drew me to them. I thought I wanted to talk about Ali with the scholar, when what attracted me to her was how she had been practicing a desire within words to story. I thought I was translating Ali into movement with the dancer, when it was her powerful desire to give the body over to storying that nourished me and gave me permission to play. In both encounters, the spectral superimposition of the archive onto the complexity of shared, living presence had blinded me to what I was longing for, the ecstasy of witnessing and being witnessed in differentiating acts of embodying story. Seeking for story through the (m)Other, a way to re-turn and re-integrate the Self, creatively transformed.

I couldn’t attune to these subtleties of desire within my research through thinking. This had been the problem all along. Rather, I arrived at sense through listening, its deep corporeality. My sound composer for the film had recently given me a homework assignment. She suggested I make a mix to give her a sense of what I was hearing within the imaginary of the project. In this way, the mind’s eye could reveal itself through the ear.

As I started to work on the mix, I stopped thinking, leaving the confines of cognition and diving into the body’s incorporated knowledge. I flipped through pages of my diary, letters I had written to Ali in the library and shared with the scholar, I browsed through audio documentation from my playdates with the dancer, I remembered songs, lectures, and interviews I had listened to online, I recalled scenes from films I wanted to associate with my film. As I worked kinaesthetically through the material, the narrative I began to hear wasn’t what I had thought it would be. Ali’s presence had transformed into something much more-than through the absence of his name, the refusal to historicize, and the relinquishing of mastery, the impulse to teach, say, show, discover. The occasion of the Other had been embodied as a sonic repertoire of “word-gestures, word-relations, word-worlds, and words-divine.”7

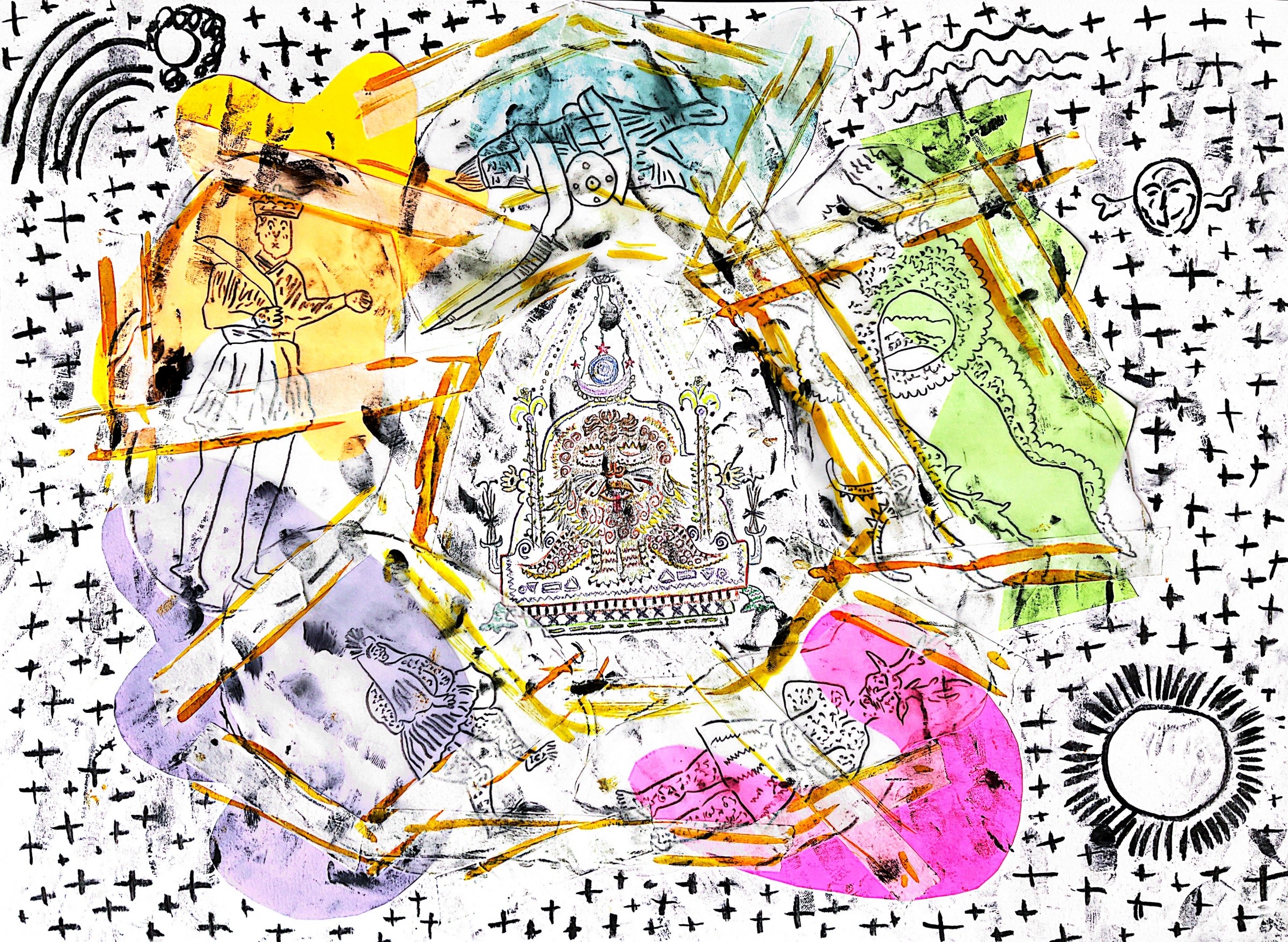

I heard the unspeakable, despite much speaking. I heard unexpected associations between primitivity and sexuality, wildness and melancholia, animality and the fantastic, holiness and the earth, heresy and the elemental. I heard the difference between male and female, him and her, the polyphony of voices inside voices, lamentation and laughter, a multitude of beings who struggle and create together. In making this mix, “my infinite original desire” (as Ali would say) showed itself briefly, powerfully, transmitted back into my body to sense out other, more playful possibilities present all along in the swirling, unconscious depths: the practice of encountering story.

Tracklist

Voices: Ashkan Sepahvand, Cecilia Macfarlane, friends, and family

Field recordings: Oxford, England, Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Berlin, Germany

Tracks and samples (in order of appearance):

Grandfather’s clock, ticking 10 hours

Shahmirza Moradi, Sangin Se Pa (“Heavy Three-Step”), Album: The Music of Lorestan

Seyed Gholamreza Nematpour, No Heaven For Gunga Din

BBC Persian Interview with Bahram Beyzaie on his play Arda Viraf’s Report

Shahrokh Meskoob, “Epic”, Shahnameh Class, Lecture 1

Reading and Translating Arda Viraz Namag from Middle Persian

Parviz Kimiavi, OK Mister, “Plastic Parade”

Parviz Kimiavi, OK Mister, “English Lesson”

Maral, Lorestan Reggaeton, Album: Mahur Club

Gholam Luti, Song in Praise of Opium

Parviz Kimiavi, Garden of Stones, “Dervish Dance”

Reza Seghaie, Daya Daya Vaghta Janga (“Mother, Mother, It’s Time For War”)

Two Zoroastrian Rituals (Part 1)

Hassan Golnaraghi, Mara Beboos (“Kiss Me”)

Mobed Mehraban Firouzgary, Atash Niyayesh (“Prayer to Fire”)