This is the second entry, written in September 2022, from Ashkan Sepahvand’s Research Diary. The first entry, “History into Mystery,” was published in August 2022 and can be read here.

I have been writing a story the past few months. It is a secret writing. It is a space I turn to when I need to work out experience without making sense of it. I’m not sure if anyone will ever read this story. But it also doesn’t matter because the words of my story inform other words elsewhere. Storytelling is a method. I don’t have a clear plan for how it develops, I take it one page at a time. Storytelling is intuitive, translational.

I’m embarrassed to admit that there’s a gimmick to how I’m writing my story. I first read a page from The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions1, treating this as a prompt. Then I write whatever comes to mind. I say it’s embarrassing because I contradict what I’ve been saying all along, namely that I’m over his story. So why do I still hold on to it? With each page I read, I cringe: his story is so quaint and superficial, its politics feels contrived, its romance is infused with unbearable white naivety.

Perhaps the unsettling feeling I get is what keeps me going on with the exercise. I read a sense of failure in between the lines. I need to feel all of this – attraction, repulsion, confusion, and alienation – because the hold of history is complex. It’s not so easy to disarm the power it has over mystery. My story translates his story not by updating or revising it, but by speaking parallel to and pressing against it, incongruously. I find this friction in-between interesting. Maybe this is how I can let go of his story, by digesting it into an unknown imaginary.

The more I write, the more I find myself interested in the energy of defeat. I connect defeat to time. In my story, something will have happened. Its times are a drag, strung along between broken pasts and static futures. It is after Revolution, after an After, it is set in the Forever-Now. There are the Luti and their Friends, they are a fabulous, fabulated Peoples. Do they exist, or will they have existed? The Times are tense, and the tense is unclear. There is Farang with its Port-Cities and Zarang with its Cities of the Plain. There is the ruling Fantasy of the Man Without Color Who Desires the Same. The Phantasma is its instrument of rule, with its Machinists and Metaphysicists, its Calculationists and Conceptualists. There is a Future-Perfect War, mediated by the Corpo-Icons. The Fantasy of Man is exhausted, it looks towards an Other frontier: the unnamable Earth, its eruptions of event, and its uncontrollable expressions. Meanwhile, the Fantasy of the End fills up an empty now-time with the sublime of an always-ending. As Lori Anderson recently sang, “what time is it, what war is it?”

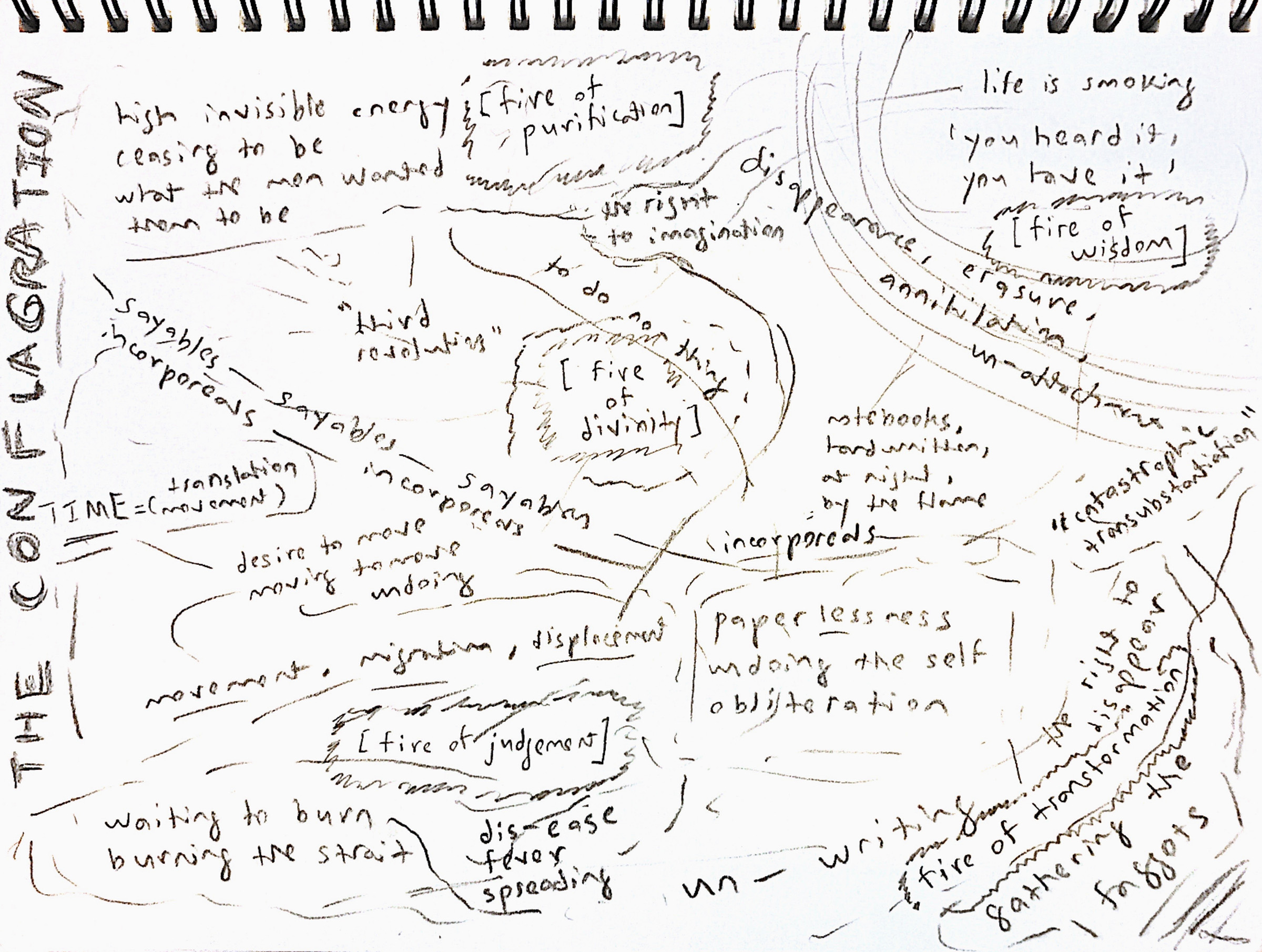

I connect defeat to fire. These untimely times are fed with ceaseless Fantasy, abounding in a heatwave of volatile desires. This has been the case ever since the Burning. Was it a fever that will have spread, a wasting dis-ease? Was it an invisible light that will have scorched vision, an enlightening blindness? Or was it a mutant radiance that will have shone, an atomic glow in the bones? How to make sense of Being in a vanquished state? How to accept the reality of defeat, to know it and be transformed? Perhaps it is like the famous Heraclitus fragment: “they change, when they are resting.” Or maybe it is like Baldwin’s “fire next time,” that roaring, potential surge which, if aroused to arise, shall be uncontainable. What if the fire, this time, burns up the soul?

I connect defeat to imagination. Imagination is posed in my story as a kind of antidote to Fantasy’s rule. It is a weak thought. In my story, I turn to face the Burning and ask, teach me. The fire replies with mysterious aphorisms:

It is amongst the scattered where home is found, not the settled.

It is through the withdrawn where thought is vital, not the learned.

It is through the concealed where the senses are sharp, not the shown.

It is through the imagined where knowledge shimmers, not the known.

It is through the unspoken where the name strengthens, not the said.

It is through the unthought where the doing does, not the head.

I spent the end of last summer in Tulsa, Oklahoma. My mother and I had moved there from Tehran when I was five years old. I remember the displacement well. There was the excitement of big airplanes as we boarded an Air India flight to Mumbai on our way to Singapore, where we would sojourn while awaiting our visas to be processed. There were the magnolia-lined boulevards (I think this was the road leading to the American Embassy). There was the McDonalds near the YMCA where we ate daily (my mother was afraid of the unfamiliar local foods). There was the hot, humid, stifling heat. And then, across the Pacific, we entered America via Seattle. I saw so much of the world in such little time and as a result, I could not unsee or unknow this worldliness.

I went to school a few months later. I didn’t speak a single word of English. The teacher gave me a pack of colored pencils, some paper, and ignored me. I sat in the corner drawing and listening. I retreated into my own imagination. That’s when my memories become a blur. The thing is, I knew without knowing that there is so much more world than this place here. I never believed in where I was as truly home. I left Tulsa as soon as I could, and I’ve been displacing myself repeatedly ever since. I guess I still can’t believe in where I am. It’s like some libidinal loop, a pleasure in never-arriving or always-departing, or maybe it’s the jouissance of turning inwards to inhabit imaginary worlds.

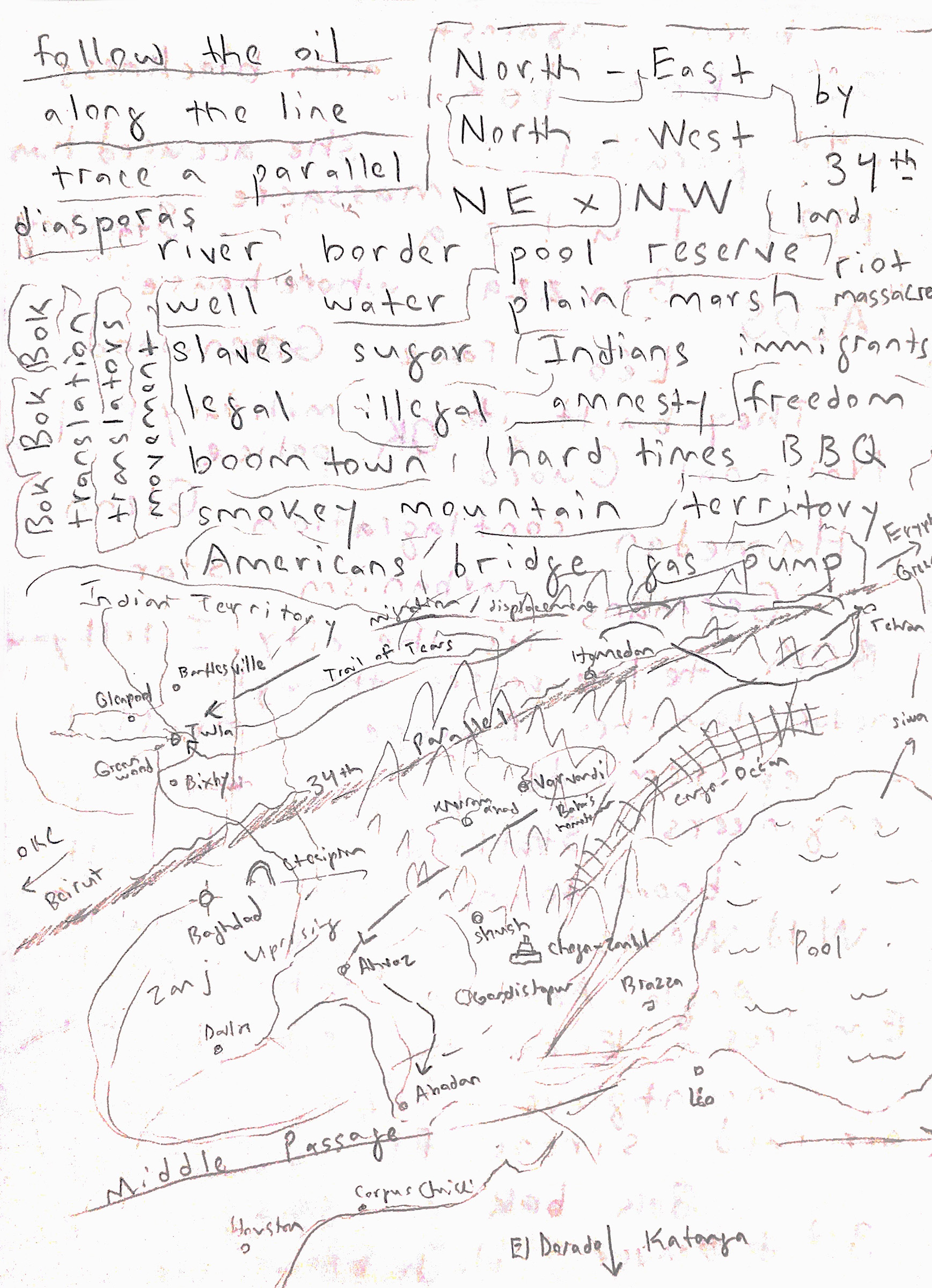

I draw a map trying to connect Tehran to Tulsa and find myself imagining timelines between cities ancient and modern. It turns out Tulsa and Tehran share the same longitude, the 34th parallel north, passing through Hamedan, Lorestan, Baghdad, Beirut, and Kabul. I follow the fuel; it is a Great Translation Movement. I imagine the railroads, pipelines, and supply chains that hold the most far-flung places together, inscribing them into a world-system of unequal need, want, and use. I think about how my father had a restaurant and a gas station, providing energy for both bellies and machines. Oil was struck in Oklahoma around the same time as it was found in Iran. Cycles of boom and bust are shared, boomtowns attract young men to leave their homes behind and seek out opportunity. A few may succeed, the rest toil, and are forgotten. There are routes to transport it all, lines that connect capital by dividing peoples and cutting through lands.

What territory is this map depicting? What memory is it tracing? Is it inhuman?

The withdrawal of Western forces from Afghanistan was on the news. The chaos of the moment was addressed as if it were both unimaginable and unavoidable. How could this happen? This was the question everyone was asking. People were desperate and struggling to leave. This was met by a disingenuous demand: everyone who wants to leave should be allowed to leave. As if departure is freedom, displacement a cure. What kind of politics is this, I thought, that desires to empty a land of its people? It felt like an uncanny recurrence of settler fantasy: terra nullius, unpopulated, open to extraction.

I remembered the time when I traveled to Kabul. While there, I kept sensing some strange familiarity. It was the memory of something I never knew. I breathed it in the air, or while driving through the wide, dusty streets. I saw it in the color of the sky, the sunset, and the mountains. I felt intimacy with this memory of nothing. It was a revived sense of worldly loss, displaced in time, and it hit me hard. How the houses and streets of my childhood were torn down to construct high-rise apartments and multi-lane highways. How the city rests at the foot of mountains, a particular horizon that provided my eye with both orientation and longing. How the soldiers at a security checkpoint moved languorously, a faint floral scent surrounding them. This aura, I remembered it, too. How my father would rarely treat himself to opium. He shaped aluminum foil into a clumsy pipe, heated the black resin on the stovetop, and quickly inhaled its burnt, sickly-sweet fumes. We smoked it together once. I felt my entire body ease into a soft, electric tingle while my mind raced, pleasurably on fire.

We drove out to Muskogee to visit the Museum of the Five Civilized Tribes. The woman working there asked us if we were native. When we said no, she asked, “what’s your ethnicity?” I liked this phrasing, much better than “where are you from?” Her sense for the difference of peoples felt vital and wise. As if she meant to say: No, you and I are not the same. No, you and I shall not be complicit in the ignorance of settlement.

This interaction reminded me of something Glissant wrote. He remarked that Christianity’s philosophical innovation had been its unbinding of belief to ethnos. Instead, belief would be universal, proper to an undifferentiated Man. This suspension of belief in and generalization of difference introduced something unprecedented into thought: the Phantasmagoria of the One and the Same.

We chatted about how despite the contingencies of our displacements, we shared a loss of ground and an endurance of territory. It seems like they – the men who fantasize about Man – keep repeating the same formula wherever they go, even if it keeps on failing each time. It seems they do not know how to be defeated.

Another day, we visited the Creek Nation Council Oak. It is located on a leafy street corner in downtown Tulsa. An oak tree is protected by a fence, next to it is a bronze and sandstone circular monument in the shape of blazing fiery tongues. It was here that Tulsa was founded, though not according to its official history of settlement by white frontiersmen.

The story goes that the Mvskoke tended eternal fires. These must never be extinguished, lest they lose themselves as a people. When the US military forcibly removed the Creek from their homelands in 1834, they took their fires with them, as smoking embers. They cared for the ashes, making sure they continued burning. This was both a knowledge of Relation and a matter of life and death. The Mvskoke trekked through the harsh winter, losing many kinsfolks along the way. They shed a flood of tears in mourning, yet no lamentation could drown out their fire. Once they arrived at their new groundless state, a burning ceremony was held under an oak tree. This marked a confluence in time, a memorial to a world-changing journey and an intention to make home again. The future city would be grounded by re-kindling the sacred fire.

I write in my notebook: “not to ignore the inferno / until the spark surprises / instead, knowledge of the embers / relating to the fire’s power / concern for a force greater-than.”

My father told me that our surname used to be something else, though he doesn’t know what. And the village where he grew up, Varvandi, is not where his family is originally from. He told me how when Reza Shah constructed the Trans-Iranian Railroad in the 1920s, it cut through Lorestan and displaced the nomadic tribes. The region was already suffering from famine and plague after the war. The tired tribes rebelled. The Shah sent his army to quell the uprising. Some of the clans betrayed their own and collaborated with the invaders. My family was one of them. As a reward, they were renamed and relocated to another village, where they became landowners.

I was curious about this forgotten name. A census from 1919, conducted by the British India Office, listed each clan for each village in the region. I Googled the names listed for Chegeni District, where my father’s family had lived before the uprising. Only one name returned a hit: a Wikipedia entry for Ali Mirdrekvandi. I read the first sentence: “Ali Mirdrekvandi (also called Gunga Din), (Persian: علی میردریکوندی) is the author of No Heaven for Gunga Din, a fable, and Irradiant, a popular epic, both written in broken English in the mid-20th century.” I was amazed. Were we related? I soon understood that my fateful encounter with Ali went beyond genealogy. It was a deeper way of making-Relation with history, storytelling, imagination, and defeat.

Ali was born in the village of Reyghān around 1921. His biography is entangled with the geopolitical ruination of life-worlds. He lost his parents during the tribal rebellion, was sent by officials to study at the Nomadic School, worked the railroad, and by the time of the Allied invasion and occupation of Iran during WW2, he was a sweeper in a coffeehouse in Tehran where storytellers would perform their popular repertoire. There he had found an English dictionary and, sensing possible opportunity, taught himself basic English. In 1943 he approached a British lieutenant, Major John Hemming, with a letter he had written in English, asking for a job where he could practice this language skills.

Ali and John developed a relationship that’s difficult to name. The asymmetry of their subject-positions and the incongruity of their beliefs can only be grasped as an outline of colonial power. There is an ambiguous relation to mastery. John encouraged Ali to practice his English by writing letters. Soon, Ali was writing stories. John revised and reviewed these in nightly sessions in the boiler room where Ali worked and slept in Camp Amirabad. After the Allies’ withdrawal, Ali returned to Lorestan and continued to correspond with John. There was poverty, unemployment, and destitution surrounding him. As if maddened by his story, he was stricken by physical illness and disturbing, demonic visions. When he finished writing, he sent his story to England by post, some 600,000 words on loose-leaf pages stuffed into canvas carrier bags. He implored John to publish his work so that he could make money from it. John replied, saying there was a worldwide paper shortage. By 1950, Ali had given up hope in profiting from his story. In a final letter to John, he vowed to become a heathen for clearly, he had lost favor with God.

Fire is a recurring figure in Ali’s story. During his service for the Allies, a family emergency forced him to return to his village. Desperate, he burned his English dictionary, as if the language were a spell holding him back from being present. He immediately regretted the action.

His job at Camp Amirabad was to collect wood and light the boiler fire. He was often covered in soot from his labors. In his novella, No Heaven for Gunga Din, a fictionalized version of himself is sent to Hell, where, despite eternal punishment, the damned protagonist, face blackened, casually reports that the “Hellishes” have simply gotten used to the burning.

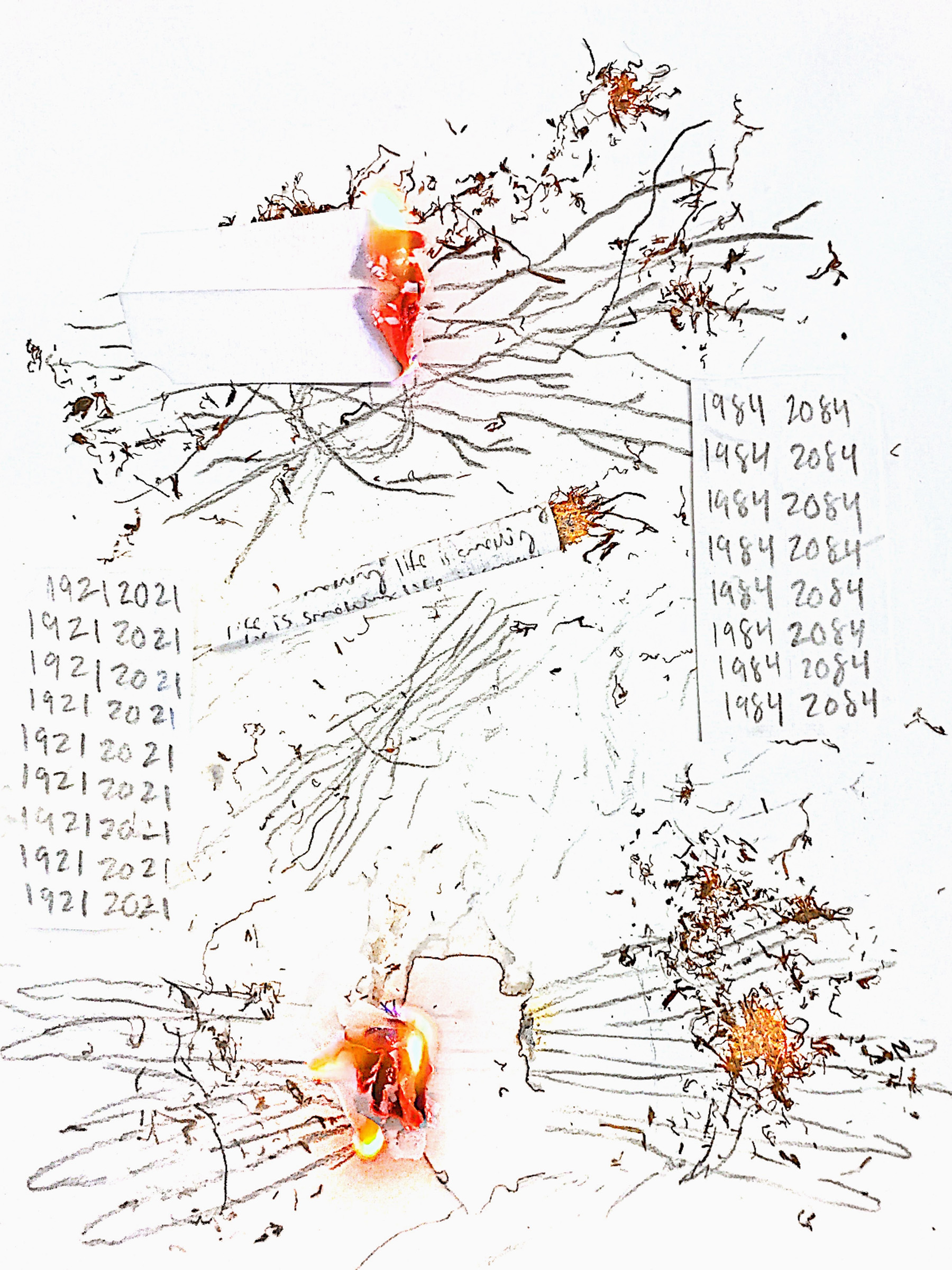

He loved to smoke cigarettes. Often his literary metaphors compare the psychic anguish experienced by a character to the desire for a cigarette left unfulfilled. He used to say, “life is smoking,” by which he possibly meant, life is as fleeting as a puff of smoke. Rumors spread that later in life, Ali lived a kind of beggar-dervish existence, dwelling in local shrines and writing stories in return for charity. He would read out loud what he had written and then burn it. One time someone asked him why he didn’t just give the story away if he didn’t want it. Ali replied: “You heard it, didn’t you? You have it.”

I think a lot about this last legend. There is knowledge at work here. I wonder how it must have felt in the aftermath of capture by Empire, to have undone one’s entire imagination through the vehicle of another language. Ali gave away his writing to John, to the English, the Americans, the world. But much more, he sacrificed his imagination. I don’t think this legendary act of burning is about destroying or withholding his writing from possession. Rather, I see in it a subtle expression of an elemental desire to protect the imagination. The fire holds his story. The reader can have it, too, only if they listen. The words remain, though transformed into the ether of smoke and memory. They have become no-thing, that is, not a thing. Through the burning, Ali relates to the unfortunate fate of his writing’s imprisonment, a performative gesture of survivance in defeat.

I’ve been making paintings while writing my story. It’s a way to translate between text and image. Luti and Crone, boundary-figures, appear in scenes of adventure, conflict, and ceremony. There are elements of Persian miniature I am interested in depicting, though without any technical skill or training. I’m learning to paint by doing. They are naive paintings. It’s important for me to not lose a wondrous sense for creation.

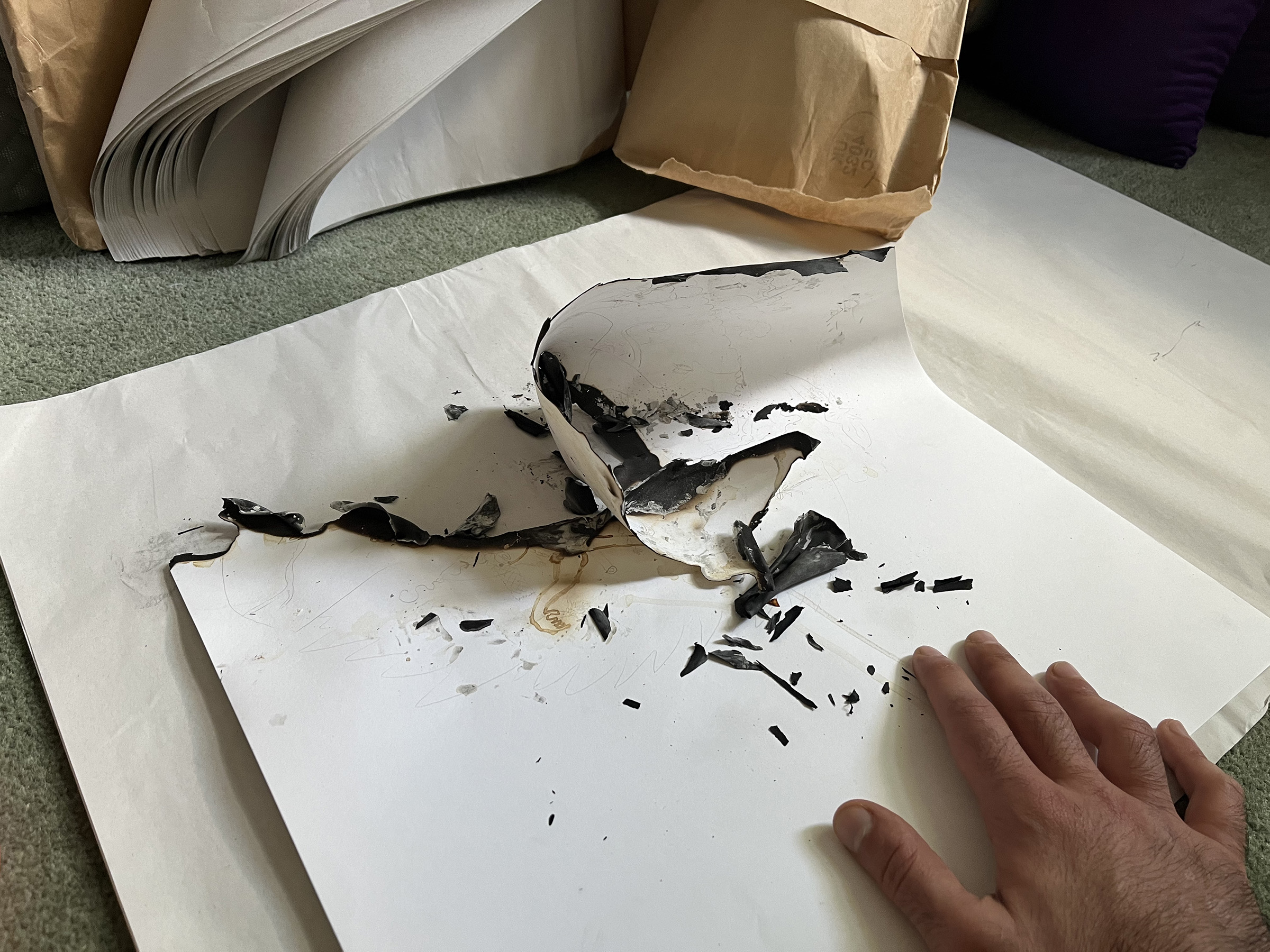

My imaginary is bound to the transformations of energy in time. That’s what I’ve learned most from the faggots – they will burn. I use materials that speak of burning: charcoal, graphite, soot, ash, petroleum jelly, paraffin, sulfur (brimstone), naphta, and tar. I sketch my figures in pencil, I trace their bodies with acid. I use lemon juice. Once dry, I finish the drawing with fire. I light a candle and hold the paper over it, carefully scorching the underside. The acid ignites faster than the paper, timing is crucial here. It burns off to reveal charred brown outlines. Bodies become visible. Any hesitation and the paper risks going up in flames. It takes some practice to get a feeling for it. Accidents still happen.

A friend of mine had recommended Shahrokh Meskoob’s lectures on YouTube. I like to listen to these while I draw and paint. They are recordings of seminars he held in his apartment in Tehran in the early 2000s. Meskoob discusses various themes in the Shahnameh, the so-called “Persian national epic,” such as time, history, creation, sovereignty, and speech. His lectures are self-consciously rambling and devoted to the marginal, often taking long dérives into comparative cosmology and philology. He makes unexpected connections between affects and beliefs.

Rather than valorizing the Shahnameh as some sort of heroic confirmation of a nation, Meskoob reads the story as fundamentally a meditation on defeat. The Iranian imaginary, he argues, is characterized by a making-Relation with defeat: to have been conquered, first by Alexander, then by Islam, yet each time to have made sense of the conquest, to have transformed the conquerors and to have been transformed by them. Victory in defeat, he calls it. I spend much time thinking about this interpretation. It seems to me that what’s most liberating here is the possibility of freedom from mastery. To not have to rule over others is the gift of having been defeated. Rather than fantasizing power-over, the imagination can attend to power-within.

I traveled to Florence last spring to visit a friend for Now Ruz. We lit the traditional fire and jumped over it. I bought new clothes, and she arranged the haft-sin spread. I picked flowers and budding branches from the garden to add to it. We cooked and ate fish, rice, and herbs. We danced, got drunk, and sang songs. It was a perfect, temporary moment of belonging.

I had just finished reading Sexual Hegemony by Christopher Chitty. It was in Renaissance Florence where sodomites were first subjected to profane bureaucracy. The cunning Medici, concerned about the rise in sodomy accusations, established the ufficiali di notte, the Night Officers, to investigate male-male relations with administrative rigor. What they discovered was that almost everyone had practiced sodomy. Traditional forms of punishment – execution, public humiliation, long imprisonment – would prove useless, as the ruling class would be grossly implicated. The Night Officers developed a modern criminal system of fines based on age, position, and class. This was an easy way for the Medici to collect money and accumulate dirt on rival families. Though discourse may still have framed sodomy as an unnatural abomination, the financialization of practice laid the political-economical groundwork for normalizing “sodomite” into a productive identity.

There’s a marginal moment in this history that caught my attention, a loose reading of Renaissance paintings depicting the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. Chitty focuses on the image of the Cities of the Plain burning in the distance. These come to represent for him the modern space of early capitalism: its reliance on urban form, its transformation of human relations, and its orientation towards “new worlds” across the seas, the realm of liquidity. I wonder why he fixates on the background. I decide to consider the foreground. I see figures moving in the land. Lot and his family, his daughters and wife, are fleeing Sodom. Lot’s wife is punished for looking back, she is turned into a pillar of salt. I find the orthodox reason for her punishment unconvincing: by looking back, she proved she could not leave behind the past.

I think about Lot’s wife, her namelessness and loss. I imagine her world-breaking experience of displacement and her suspicion of apocalyptic futurity. Why should she not look back? Why should she not want to remember home? Why should she not claim the right to view her forced departure as unfreedom? Why should she not grasp the present in the past? If the Cities can be read as ciphers of capital’s unsettling social contradictions, then the complex “family constellation” of Lot’s flight and his wife’s transformation might be viewed as an imaginary of facing defeat. Lot’s fate is to live displaced. His wife becomes part of the land itself. As salt, she nourishes the emergence of other life forms. Who is victorious here?

I kept a fire journal for writing after my burning practice. It’s a habit of mine to overdo and overthink things, which often leads to exhausting a practice. It soon becomes too much for me to keep it incorporated into my routine. I eventually get tired of it and move on. I gave up fire journaling, it felt too self-conscious, but it’s interesting to revisit the writing now.

I had made a note of something I read: in Moroccan Arabic, a slang word for Europe is l’harq (حرق), “the Burning.” This refers to a practice by those who migrate illegally to Europe. Before setting off on the journey, they burn their documents in order to make it difficult to identify them if caught. “Europe” is renamed as a void of identity.

Burners, as they’re called, employ techniques to avoid capture. They insist on their right to dis-appearance. The journey is a trial by fire, passing through the mortal risks of Judgement. Is this some kind of intimacy with defeat? For some Burners, the act of becoming-paperless carries its own particular jouissance – an infernal commitment to keep on the move, freedom of mobility through self-obliteration. The Burners know they will be changed into unknowable beings. Undoing the self, this is a dangerous practice.

Elsewhere in my journal, I find notes from Susan Buck-Morss’ Year 1. Back to the first century – the Alexandrian Moment – Buck-Morss time travels with an urgent question: how to get over History and its fantasies of time? To fall out of modernity. She re-reads the Book of Revelation, also known as the Apocalypse, re-animating the utter strangeness of the text. Here, Buck-Morss carries on Foucault’s late interest in transcendence and connects this with translation. Transcendence is untranslatable in the language of modernity, whose belief is in timeless concepts. How to undo and unknow the concepts (history, crisis, progress, Man) that hold the times captive, the ahistorical idea that “they” then and there have failed, that “we” here and now are better? How to release the “end of the world” from the stillstand of fantasy?

It all comes down to words and their mysterious polysemy. What happens when words are read against the grain of their appropriation by history’s victors? How do meanings from the present imperfectly align with names of the past? In other words, is there a secret language of the defeated? What is heard, where does it hold, and when does it transform time?

Source: Unknown, found on social media.

A Fire (POSTSCRIPT)

A week after I finished writing this text, a wave of protests broke out all across Iran in response to the murder of Mahsa Amini on September 16th, 2022 by the Gasht-e-Ershad (“morality police”). Coming together underneath the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom,” women and men, young and old, have poured out onto the streets to risk their lives in denouncing tyranny. Their grievances are many and complex, from the oppressive persistence of patriarchy, the subjugation of women’s bodies, the hopelessness of opportunity for youth, the dire economic situation (exacerbated by international sanctions), and an ongoing disillusionment with official discourse on “revolution.” The situation has only intensified in the past days. Internet has been shut down across the country and, as to be expected, reports of violent crackdown and arrest have emerged. Around the world demonstrations have been organized by Iranians in diaspora to show their solidarity.

Encountering all of this from the in-between has been difficult for me. I feel both transfixed as a worldly witness and unravelled in my diasporic subjectivity. What desires are being unleashed in this moment? There is hope, fear, longing, anger, and grief. What language of the future do we have to speak of an “after,” after the revolution, after tyranny? How does this translate to other struggles elsewhere, especially when today’s politics seems to offer little choice between anti-rational, militarized populism or apolitical, neoliberal humanism? There is so much at stake in a people’s political imaginary. As Alex Shams recently wrote on Instagram, “protest is not just about succeeding, it is about imagining another world.”

It feels necessary and important for me to acknowledge the contemporaneousness of what’s happening in Iran with some of the embodied reflections I’ve shared in my text here: thoughts on defeat, transformation, history, and fire, the practice of making-Relation with forces greater than, the strange wisdom to be gleaned from the ashes. The main gesture that has come to symbolize the current protests is fire. I see images abounding of women setting their headscarves on fire or throwing their coverings into collective bonfires and dancing defiantly in a circle afterwards. I am very moved by this fire and this time. What is this Burning trying to say? I don’t feel equipped to comment on this further, but I do think a lot about the mysterious ways in which real life concords, however temporarily, with the secret workings of words and names. To quote a recent blog post by Mona Eltahawy, the women of Iran have “set our imaginations on fire.” The task at hand is to protect this imagination from capture.

All images are courtesy of the artist, except for the last one.