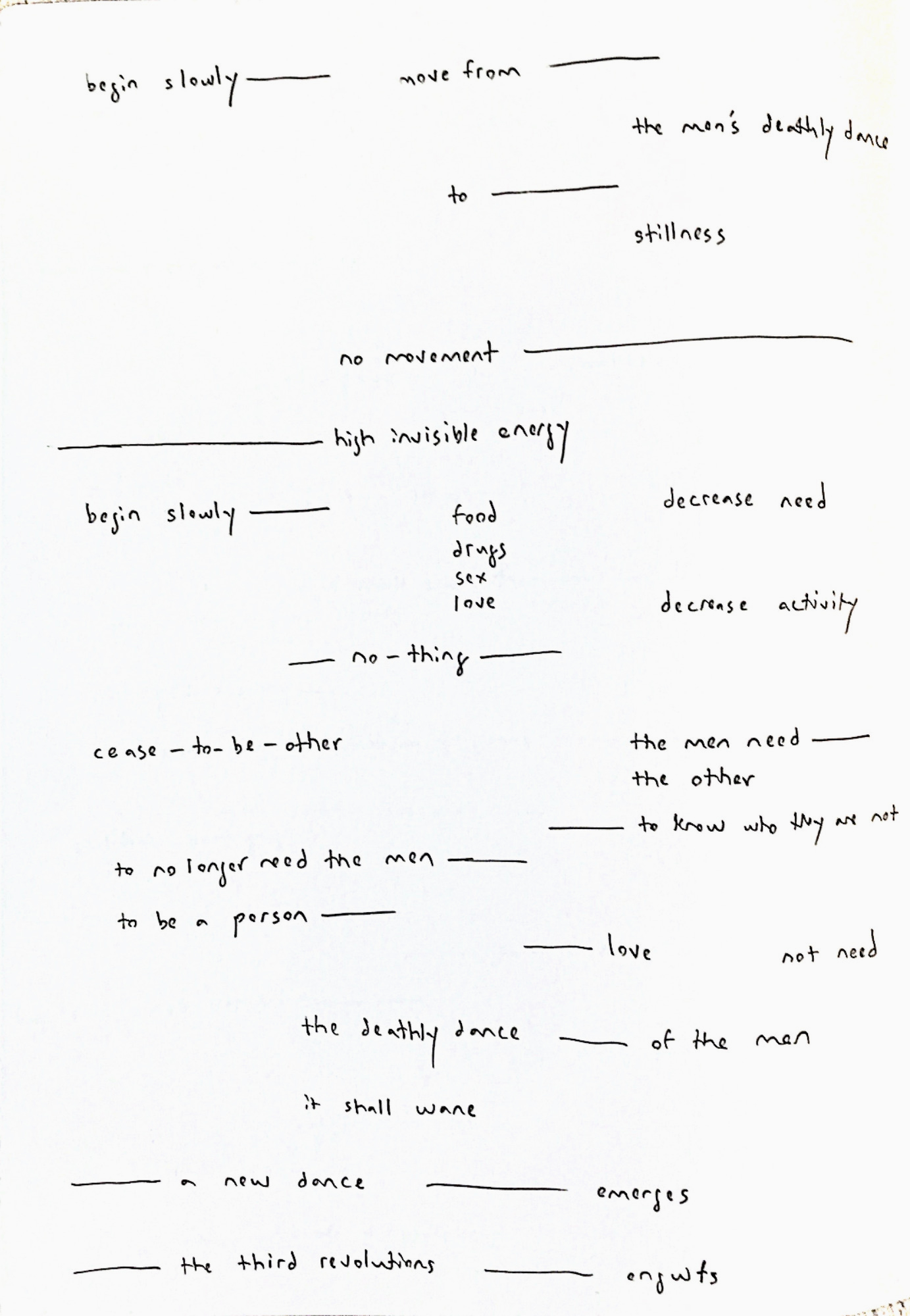

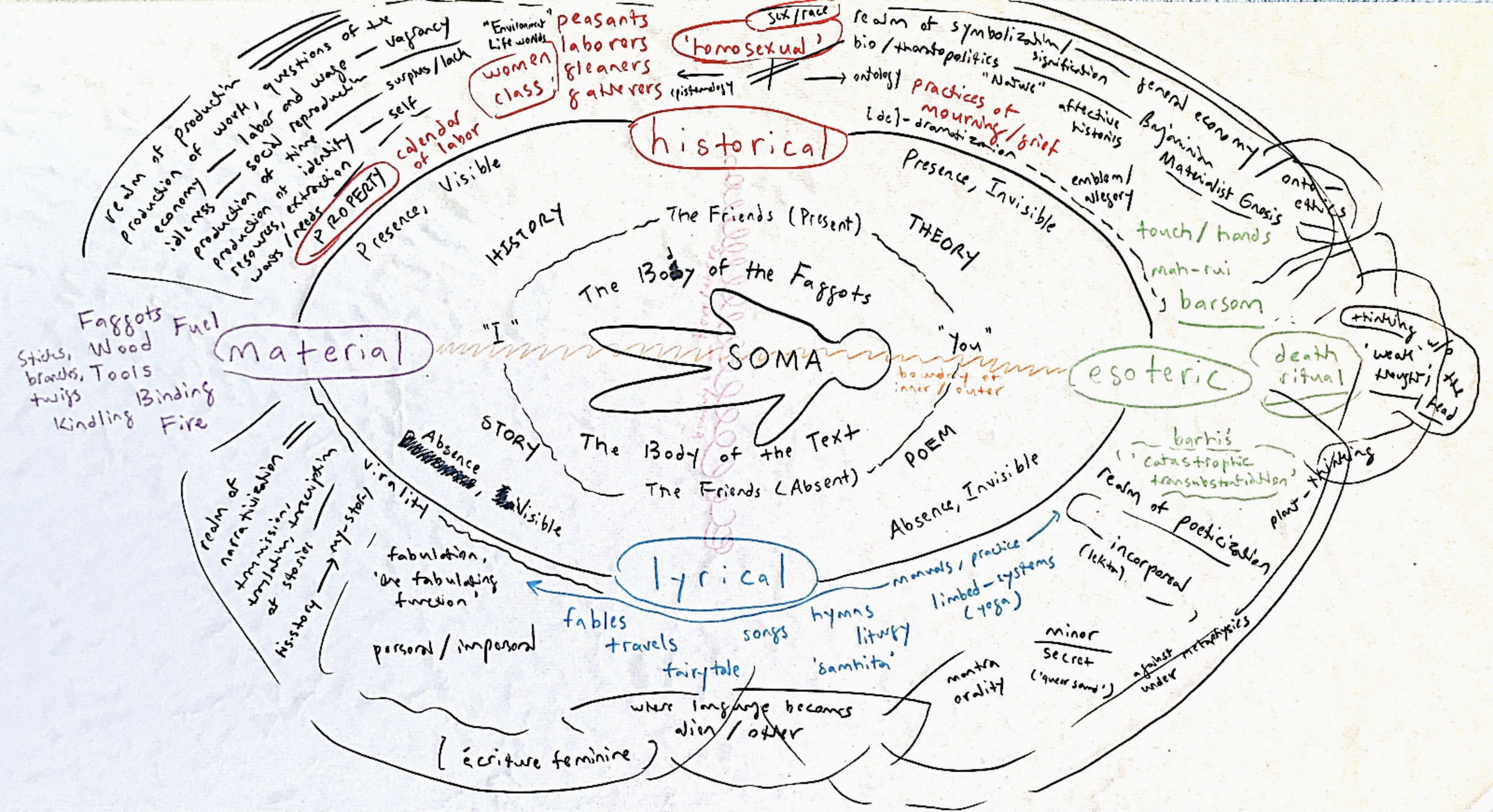

When I read now, I no longer take “proper” notes. I jot down words and phrases that move me and spread them out on a page. There are lines and empty spaces, there is movement to the writing. This helps me to let go of the words.

I’ve been reading The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions by Larry Mitchell from 1978. However enchanting, I remind myself that he’s just another North American, white, gay man. This history isn’t universal.

Reading the last chapter of his story, it strikes me how mystical this fantasy of revolution is. I think about how this faggot ideal would soon be shattered through the AIDS crisis, with its devastating effects on the homosexual subject.

I guess my story intersects with this somehow, but there’s also the unavoidable fact that when this text was written, the Iranian Revolution had just started. Its after-effects on Iranian subjectivity have been complex. That’s my story, too, in a way.

I don’t think any of this is coincidental. I wonder how my in-betweenness holds within it a condition I want to call post-revolutionary. Is it possible to describe a shared state of withdrawal – the shattering of revolutionary idealisms, the rupture of traditions, the uncanny sense of an “after” – between my two historical identities?

I don’t want to think about these questions scientifically. There’s nothing to know. I decide to go back to words, to feel out what they are trying to say, to follow intuition. Maybe words have a secret, maybe words know something their speakers don’t.

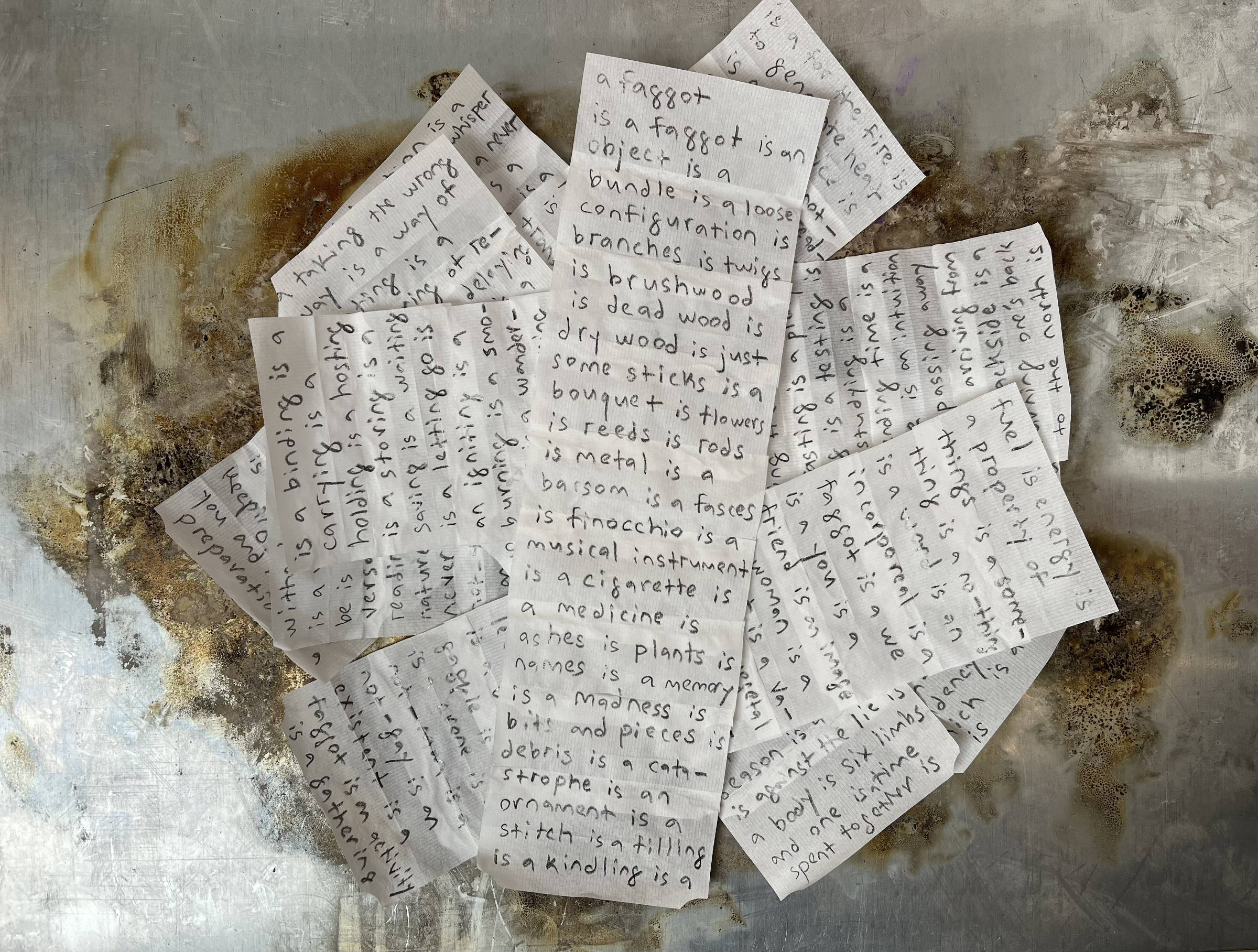

Take the word “faggot,” whose original meaning from the 13th century is a bundle of sticks used to start a fire. The word migrated into English from the French fagot, and some etymologies trace it back to the Latin fascis – again, a bundle, but symbolic of imperial power. “There’s always a fascist in every faggot,” I catch myself in a pun.

The word has signified quite a lot in its thousand-year use. I write out all the associations onto cigarette rolling papers I’ve licked and stuck together to form small scrolls. Fag papes. There are bundles for fuel, bunches of flora, groupings of peoples, unruly women, effeminate men, loose configurations.

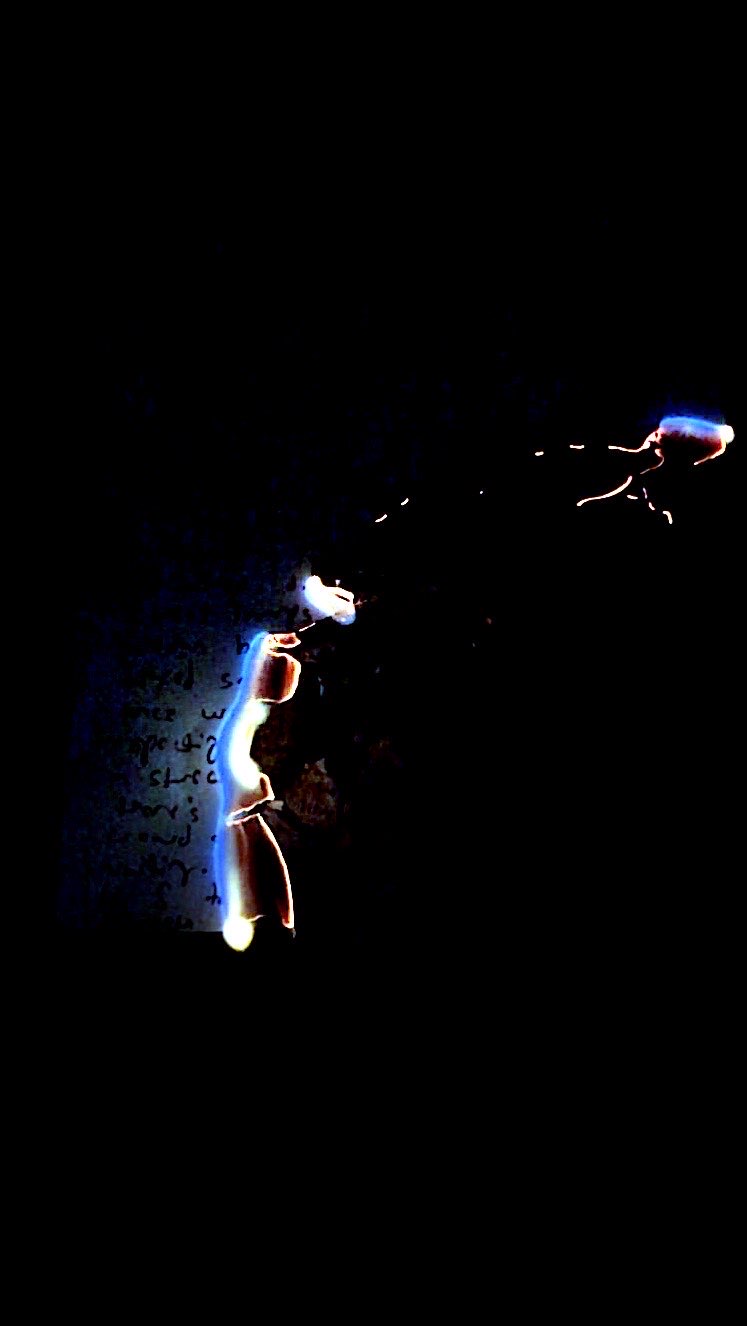

In Greek philosophy there’s a beautiful word, lekta, meaning sayables: words may not be material, but their immaterial persistence maintains corporeal existence. It’s all anyway moving towards cosmic conflagration. What if the fate of the faggots is, after all, to burn?

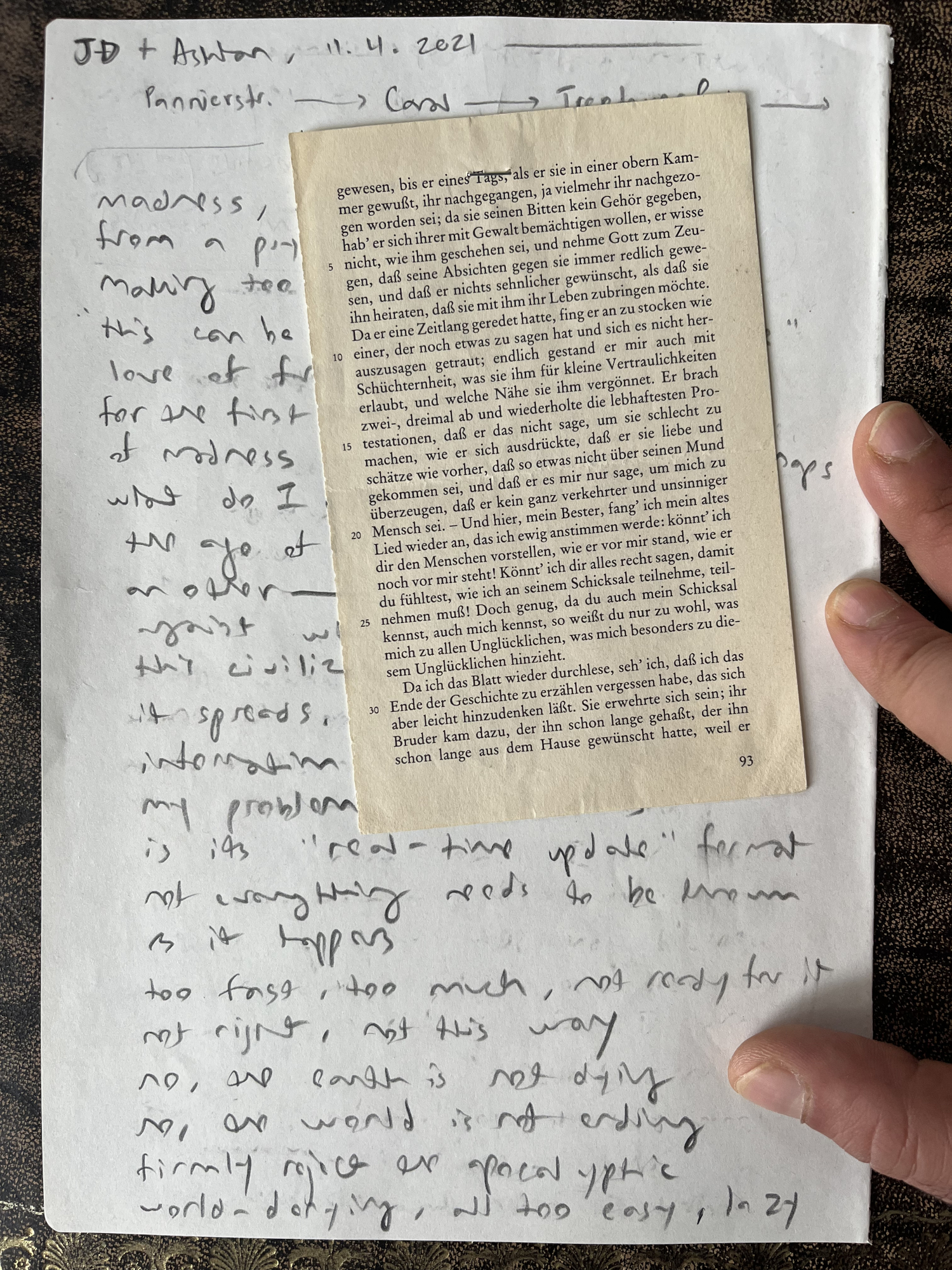

I like to start the new year with a ritual. Like the time in Siwa, Egypt, when we visited the Sibyl’s Temple. The night before, the roaring fireplace in our house spat out a page from a novel written in German. My friend gave it to me, knowing I was the only one who could read it. “Here,” he said, “this is your oracle.”

Or, like the Iranian tradition of jumping over a bonfire. There’s a song that goes with it: “my yellow to you, your red to me.” Take my sickness, give me life.

I’ve been stuck in my writing for some time now, blocked by His Story. So, I decide to burn it all. I write a page and then set it alight. I’m not destroying anything, that is clear. I burn in order to write otherwise. I am seeking transformation. I think of it as sacrifice: I give something concrete away, I get something unexpected in return. It’s mysterious.

During last year’s lockdown, I asked six friends to go out and gather faggots with me. Each friend chose where we would go, bringing a material to bind the bundles of sticks, twigs, and branches we collected. Gathering faggots was a way for us to do nothing in that time, which was very much something to do.

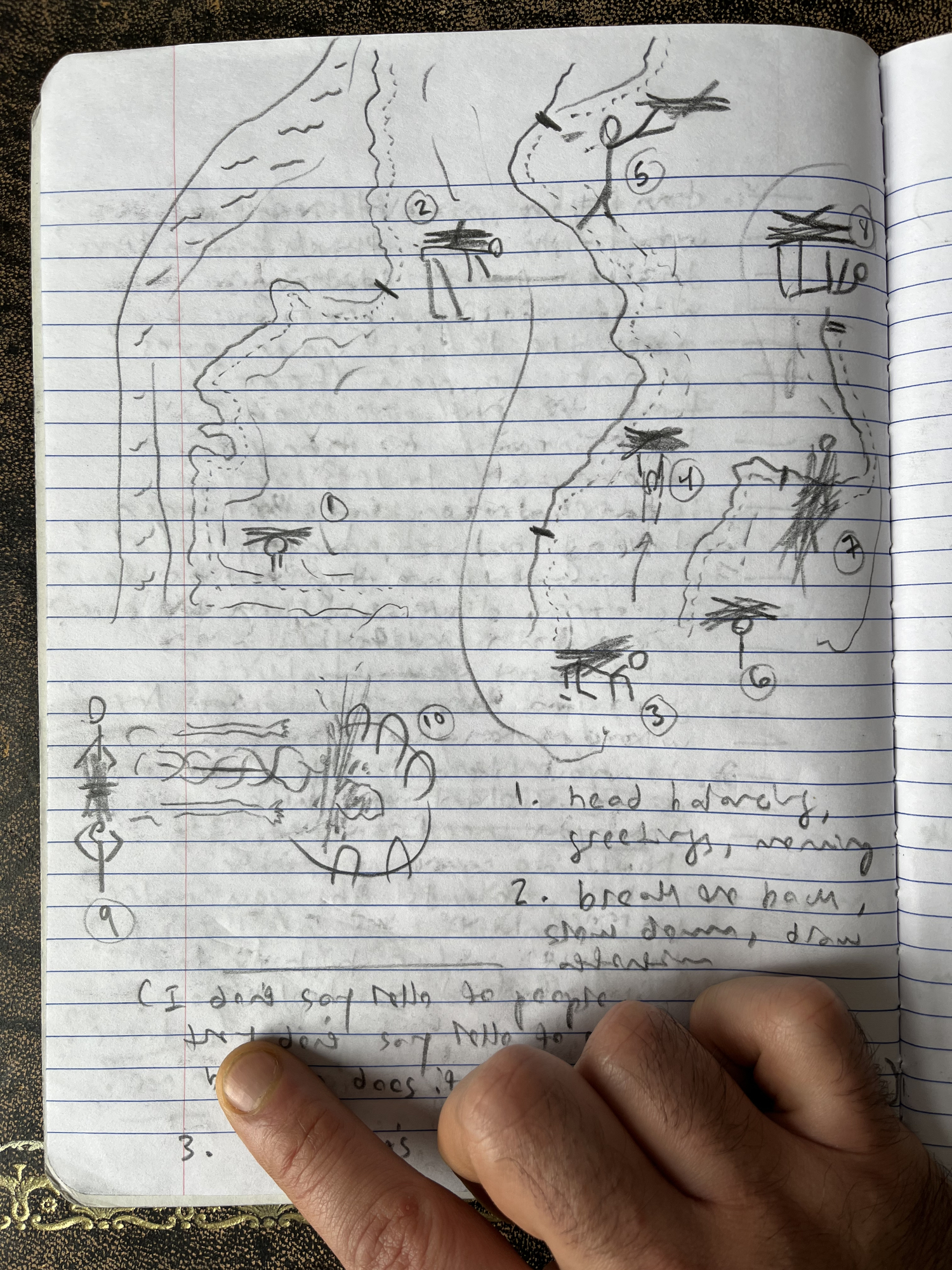

Conversation flows so much better while walking. Thought needs to move. I wrote down notes from memory after each outing. Writing by hand recreated that sense of movement on the page: words walking, there is flow, there is a jump, a shift, a vitality. The hands get tired, much like the legs. I feel it.

In all of the places we went to, we would always seem to pass through or near cruising areas. A friend pointed out how that hill over there, where the men lingered, was built from rubble piled up after the Second World War. Bits of ruin and slabs of concrete stuck out from the earth. “What does it take to break a bunker?” she asked.

One time, we found a copy of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther lying on the path. My friend picked it up and a page fell out. I kept it, knowing this was another oracle.

I look at the excerpt now and the following line catches my eye: “Since I’m reading the page again, I see that I had forgotten to tell the end of the story.”

I took the faggots out to the countryside with me for a week, I wanted to spend time with them.

I realized each one was an unknowable body. Each faggot had a shape, a personality, its own gestures, colors, textures, and weight. They came not only from somewhere, but somewhen.

There was, of course, the memory of the friends, the associations in the choice of binding, all traces of the human, but I wanted to avoid this symbolic habit. I wanted to encounter the faggots in their strangeness, otherness.

I had been training in somatic practice and felt great resistance. It was the whitest of spaces. Round after round of sharing revealed how those around me were preoccupied with the discovery of having a body. All I could think of was how I had lived my entire life not having but being a body. For the first time, I lost the ability to listen. I felt anger. I didn’t want to empathize anymore with white lament around property.

The teachers spoke a lot about the ground and the breath. There is always ground, there is always breath. It was all so assured and reassuring, so sure of universals. I wondered why white somatics turns away from the dark. What if there is no ground, what if it’s slipped away, what if there’s nowhere to land, what about the displaced? What if the air is toxic, what if the disease gets into the lungs, what about those who can’t breathe? What would a dark somatics feel like?

I sat with the faggots in a reading circle. I laid down with them to rest. I took them outside and we danced together. I stroked and caressed them. I unbundled one and placed its branches up my sleeves and down my shirt, these felt like bones. It was a full moon one night, so I improvised a ritual with them. One faggot made me cry, my tears and spit soaked into the wood.

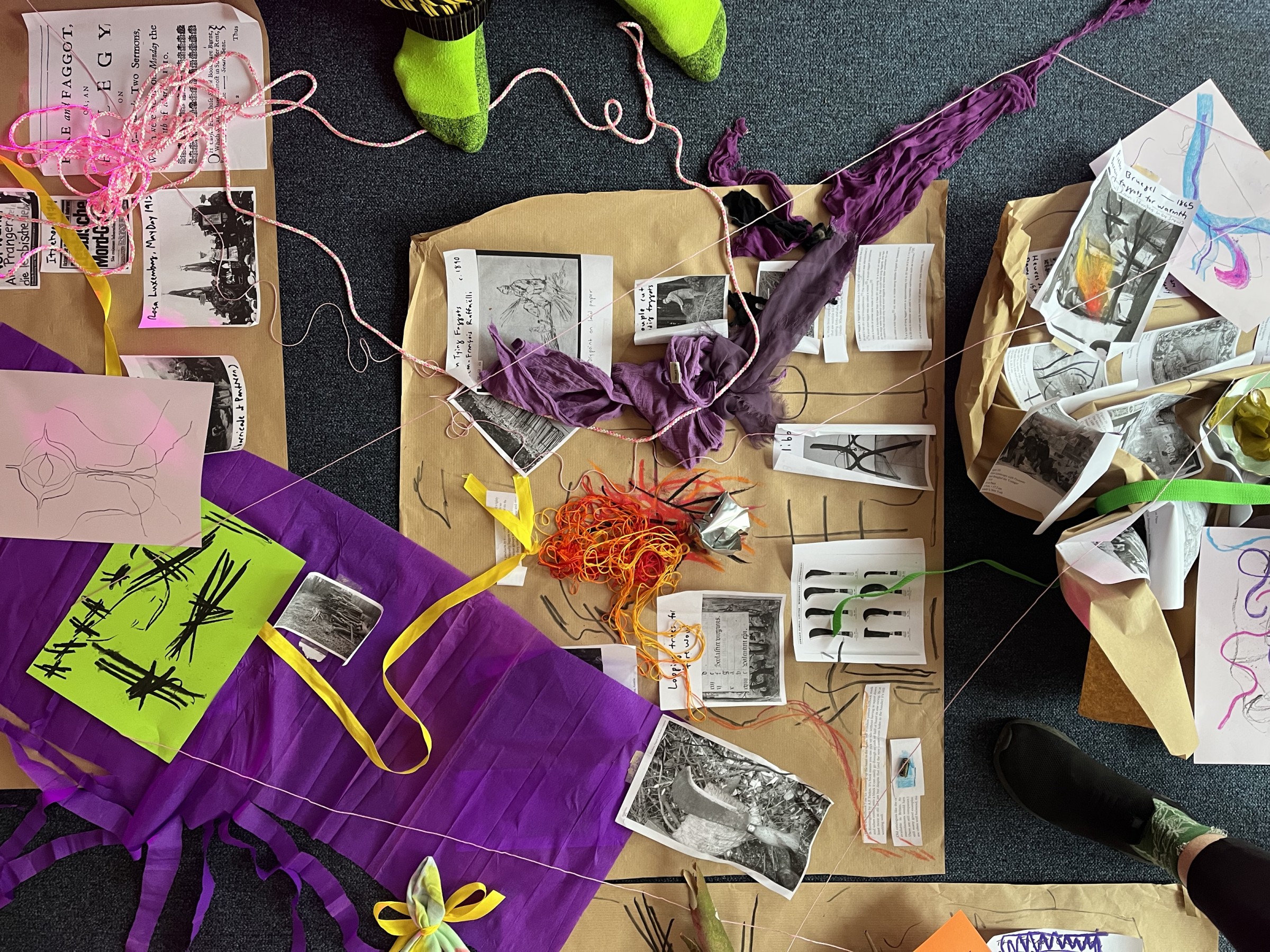

I invited the friends to join me and the faggots for the weekend. It was around the first of May. The significance of that date did not escape me. A celebration of fertility, the warding off of malevolent spirits, the burning of effigies, the marches of laborers in solidarity.

The friends decided they wanted to perform a death ritual. So, we did, with the faggots as our body. We cooked a feast, danced until we dropped, then adorned and adored our body in silence. The next morning, we woke early and carried the body through the woods. As we unbundled it and gave the body over to the waters, a friend recited the Mourner’s Kaddish. Not far away from where we were, there was the site of a former concentration camp.

Is this how traditions are created? The energy of doing without knowing.

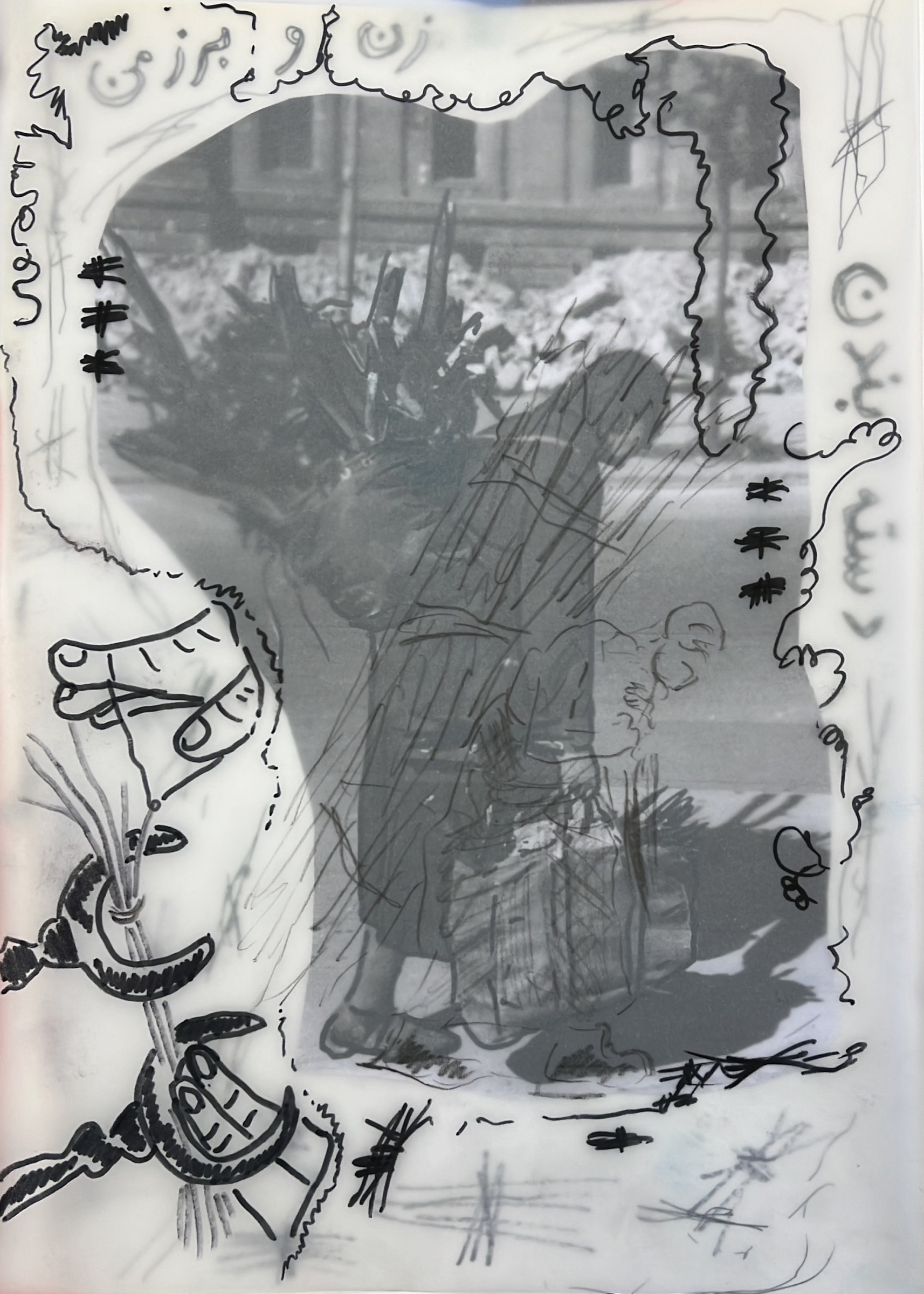

Since then, I find myself repeatedly drawing a figure. It is surrounded by energy, a forcefield of lines and colors. Its points of articulation are marked and bound. It is a radiant figure. Is it a leftover trace of something that once was? Is it a transformed being, a spirit, or a soul? Is it an otherworldly creature, an angel, or a demon? Is it an incorporeal, an envelope of the imagination, resonating with words? What materials make up its body?

What am I trying to remember?

I’ve made a new friend. She is a dancer in her 70s. She teaches weekly classes where anyone can join. That’s how I got to know her. We were curious about each other, so we agreed to meet up and play one on one.

She shows me a book she’s been reading, titled Crones Don’t Whine. I like this word, “crone.” It’s both crude, an ugly insult, like hag, as much as it’s fantastical, evoking fables, like the woman of the mists.

She likes to work in the land. So, I suggested we play in the woods near my house. It’s a strange place. What used to be an industrial gasworks is now a nature reserve. There is a railroad that cuts through the place, on the clock the sound of hurling metal. There are remnants of small parties, ash heaps and litter, there are signs of the homeless camping out in makeshift tents. Every now and then, bag people wander by, staggering.

We found a circle of pine and eucalyptus trees. This becomes our site. The railway tracks are right behind. Nearby there are dense bushes where I’ve noticed men waiting around, staring at each other. They must be cruising.

We meet to play all autumn and into the winter. One day we take turns carrying a faggot on our backs. It is a large, heavy bundle. As one of us bears its weight, the other asks it questions. The reply is in movement.

I am drawn to the floor. It reminds me of childhood. Eating around the sofreh. Rolling on the carpet. Drawing with colored pencils or reading a book on my belly, my elbows getting rug burn. Sleeping side by side on futons, they were so hard, the next day we’d fold them up and stack them in the corner of the room.

I think better when I work on the floor. There, I get a sense that I can move into and between the spaces of my imagination. I want to touch, to be immersed, to inhabit the surround of thought.

There’s also something about bending over, looking closer, squatting, and waddling. The physicality of the floor is more demanding, it makes it easier to get out my head.

My friend and I meet to play indoors. We spread out our images, objects, and materials onto the floor. The rule is to work in silence. Everything is scattered, displaced, it’s all just a pile of scraps, really. There is a loose and playful bringing-together of disparate things. We bundle and unbundle. It feels like this practice both reveals unexpected associations as much as it conceals definitive meaning. The desire to make sense unravels itself.

I wear bright, neon-colored socks that day because I know we will be taking overhead photos and my feet will probably show.

When I trace an image, I feel closer to it. But tracing also helps me to see many images all at once, to insist on simultaneous vision.

There’s a photograph from September 1945, taken right after the war ended in Berlin. It moves me. An old woman walks through streets lined with rubble, a sack of firewood on her back, another in her hand. Woman Staggering Under Her Load of Faggots is the image’s title.

It reminds me of Millet’s paintings. After the 1848 revolution, the disenchanted artist moved to Barbizon, a village on the outskirts of Paris undergoing slow ruination by modern industry. The faggot-gatherers were one of the many tropes of peasant life he depicted. They were always women.

I trace an image of the magi’s hands touching the barsom, the sacred bundle of twigs in Zoroastrian ritual. The barsom are touched like electric wires to activate a cosmic current. With this gesture, the priest-king seeks power over the unruly forces of nature.

Faggot came to mean old or disorderly woman in the 16th century. This was around the time of various enclosure acts, persecution campaigns, and trade professionalization that ruined the lives of Western European peasantry. It was the women who carried it all, unbearably.

What desire draws me to these figures?

I remember carrying my mother’s sense of loss as a child. Her loss of homeland. When we traveled, I lugged our bags, put them on trolleys, I held her hand, I asked for directions, I spoke for her. My backpack was very heavy. I wanted to carry it all. It made me feel strong. Did I choose this or was I asked? I don’t know.

My father broke his back at work when I was a teenager and as a result, he closed his restaurant and filed for bankruptcy. He bounced back alright, I guess, though always a bit broken. His joy still lies in bemoaning this tendency towards brokenness.

I was invited to teach an online seminar with young artists in Iran. I wanted to share a text I had written about death rituals, but it needed to be translated. I decided to do it myself.

For a long time, I thought my Farsi wasn’t good enough. I lacked the right vocabulary, my syntax was full of errors, I had an American accent, it wasn’t “proper.” I was embarrassed by my broken Farsi, as if my life in diaspora had ruined it, deforming its ideal original.

All of these were excuses, I realized. What does it matter if a language is broken when the times are in ruins? What if my diasporic tongue was the strange future of a language that had long already started to become other to itself?

I wanted a word for faggot that carries the same polysemy in Farsi as it does in English. Not the same meanings, rather, an incongruous translation.

My father told me how when he was a child, a group of luti came to his village. He wanted to run away with them. I was confused. Luti was a word I knew from Arabic; it means sodomite. I laughed and asked him why he wanted to run off with a bunch of pederasts. He didn’t see the humor. They were musicians, he told me.

The word luti does mean sodomite, but once it entered Farsi from Arabic, its significations expanded. In its thousand years of use it has meant mystic, dervish, vagrant, vagabond, bandit, wrestler, roughneck, musician, performer, and entertainer. I had found my translation.

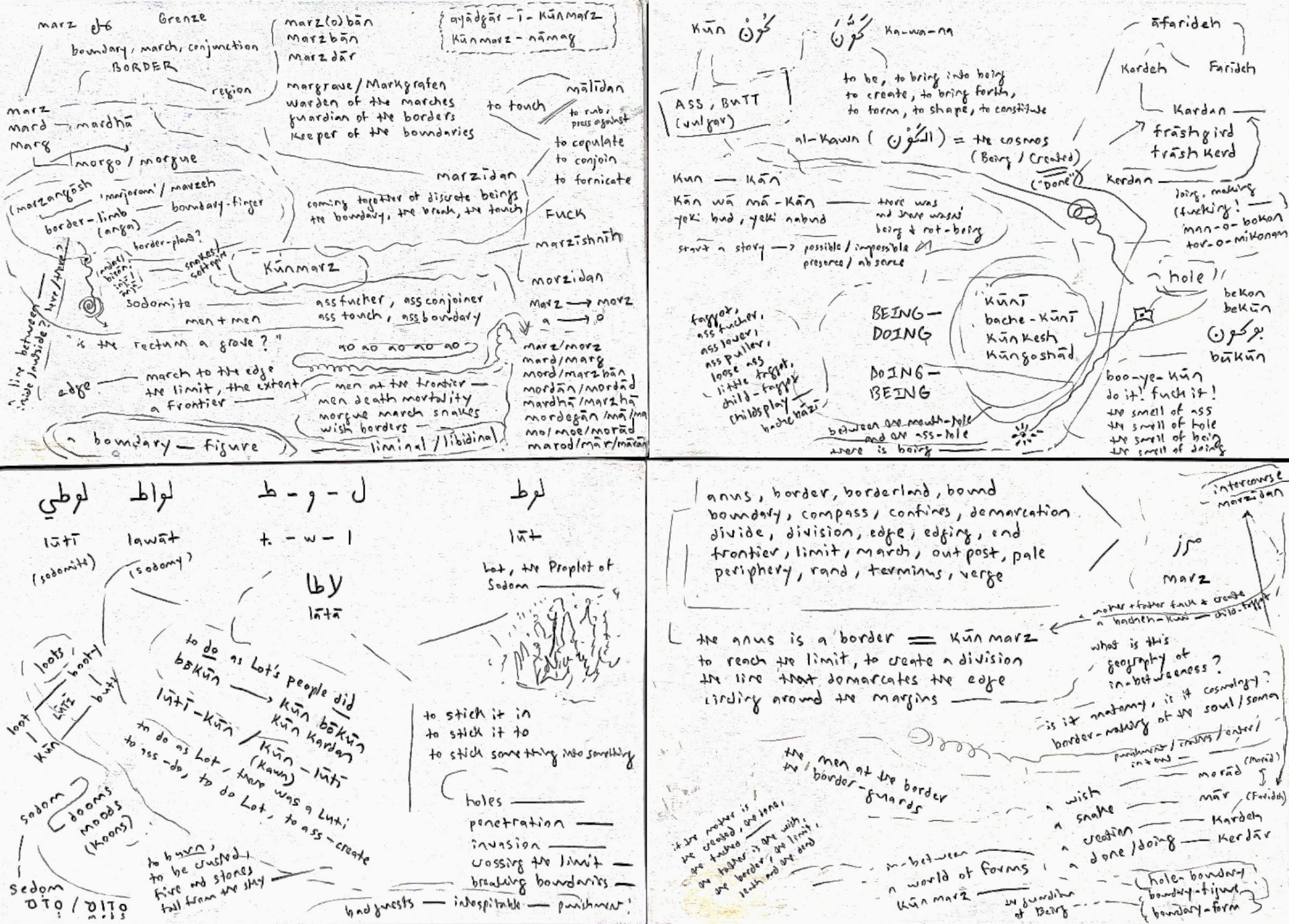

All of these figures have something in common: they are marginal, they are othered, they are bodily. I talk about this with my psychoanalyst. After our session, she calls me. This is unusual. She’s looked up the Middle Persian word for sodomite and wanted to share it: kunmarz. I reply with a cackle, it’s a funny word. Kun means ass and marz means border. How literal.

I spend a few days reading a Middle Persian dictionary, studying the words of a dead language. Is it the unconscious of a living speech? The words for border cluster around the words for intercourse and touch. I turn the page and the same sounds shift ever so slightly to form a cluster of new words meaning men, snakes, and death. The word for ass is similar to the imperative form for the verb to do and, by coincidence, it’s the same letters as the Arabic verb to be.

These sayables know something that no speakers know. In the in-betweenness of my many tongues, there is a displaced memory. I remember the boundary-figures, those who come from the in-between. Their story is the mystery I desire to believe.

All images courtesy of the artist, 2022.