Chantal:

“I have always been protesting against the world, the political world. During my childhood, we had many family discussions about politics. My parents had a subscription to Témoignage Chrétien [Christian Testimony], a leftist christian magazine. It supported the independence of Algeria, all independences and decolonization. When I was a teenager, a local priest took me to the Jeunesse Ouvrière Catholique [Catholic Youth Workers], where I met people who were very much into politics, into defending workers. It was a very important experience. I was never an activist myself, for different reasons. But I have been marked by the founding of the State of Israel. I thought it was unbearable. It became a strong subject of conflict between my father, my brothers and I since I have been 15 years old.”

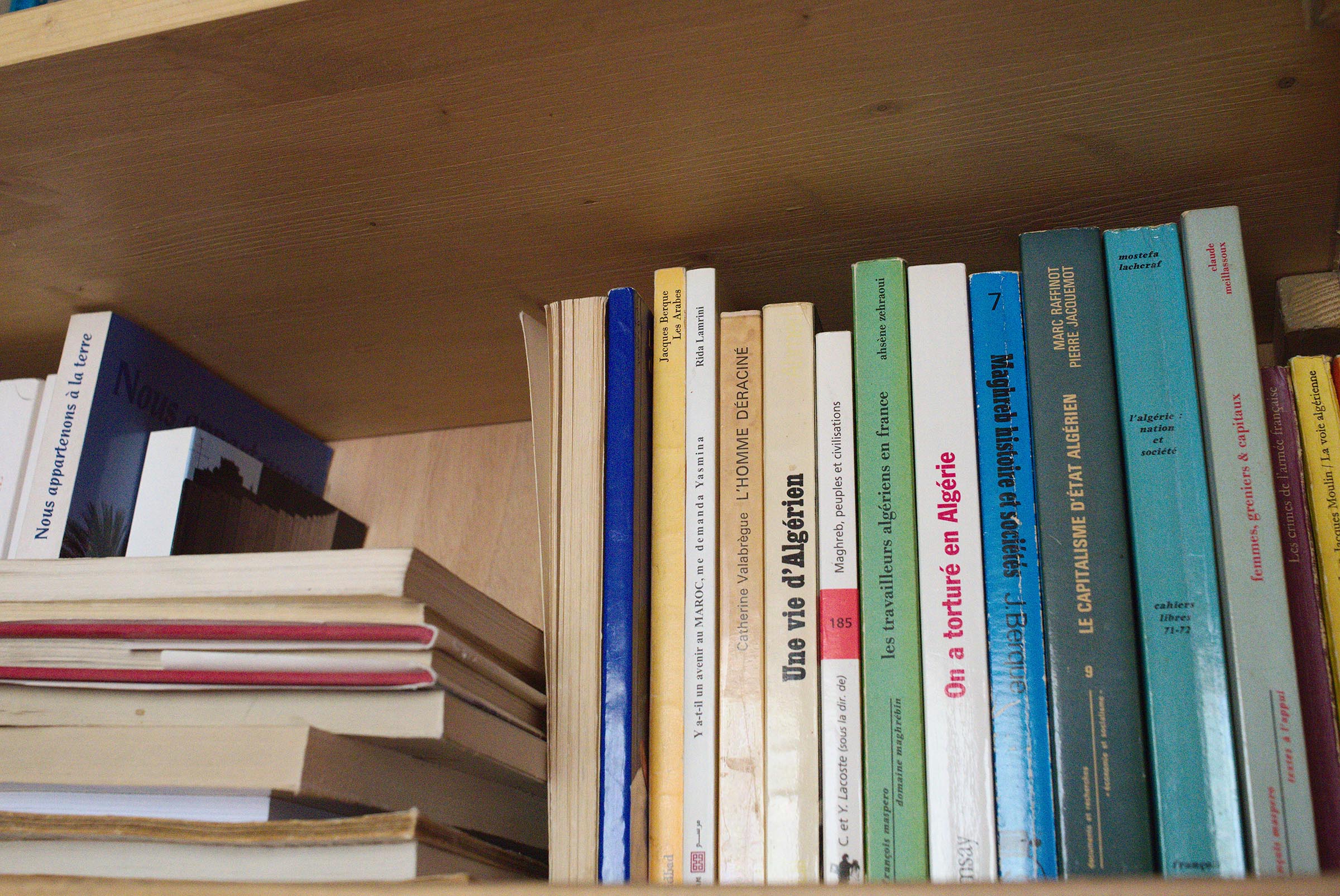

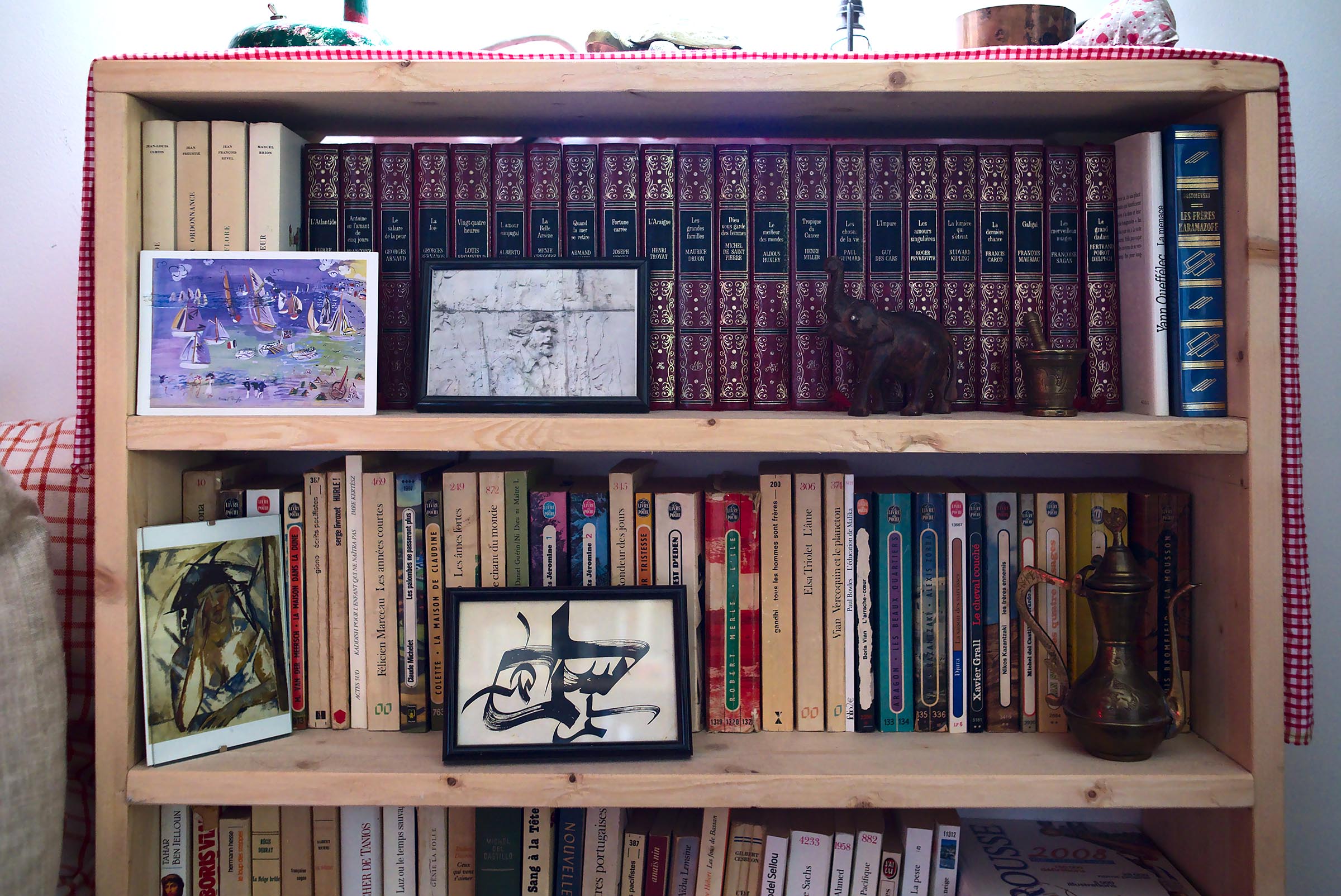

“From very early on, I was interested in the Algerian revolution. I have many books about the Algerian experience: sociology books or studies about the country’s organization. I had the opportunity to travel to Algeria in 1978 with an organization. I bought most of my books before my wedding. Because, after that, I had other things to pay for and I bought less books. There was even a time when I did not buy books anymore at all.”

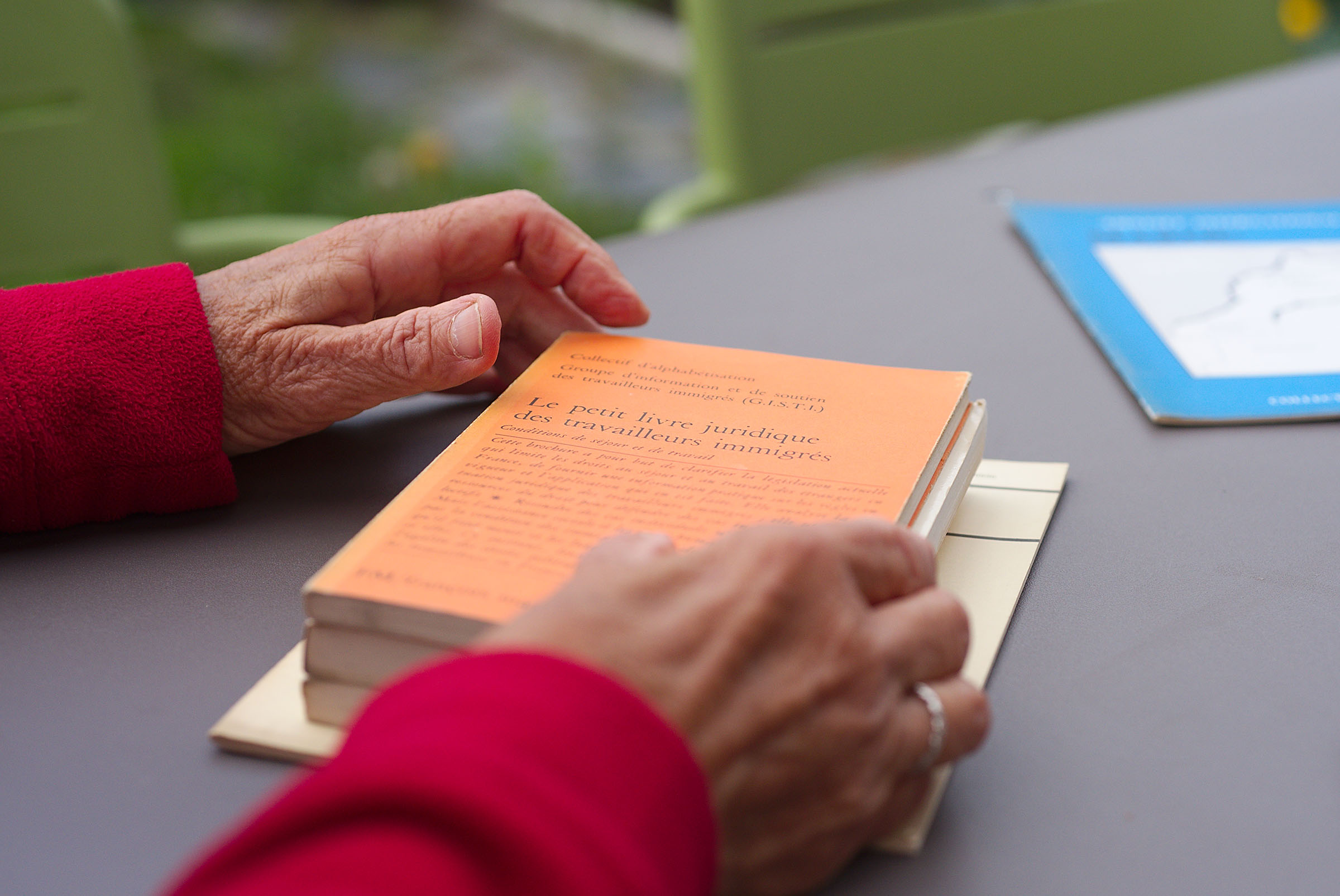

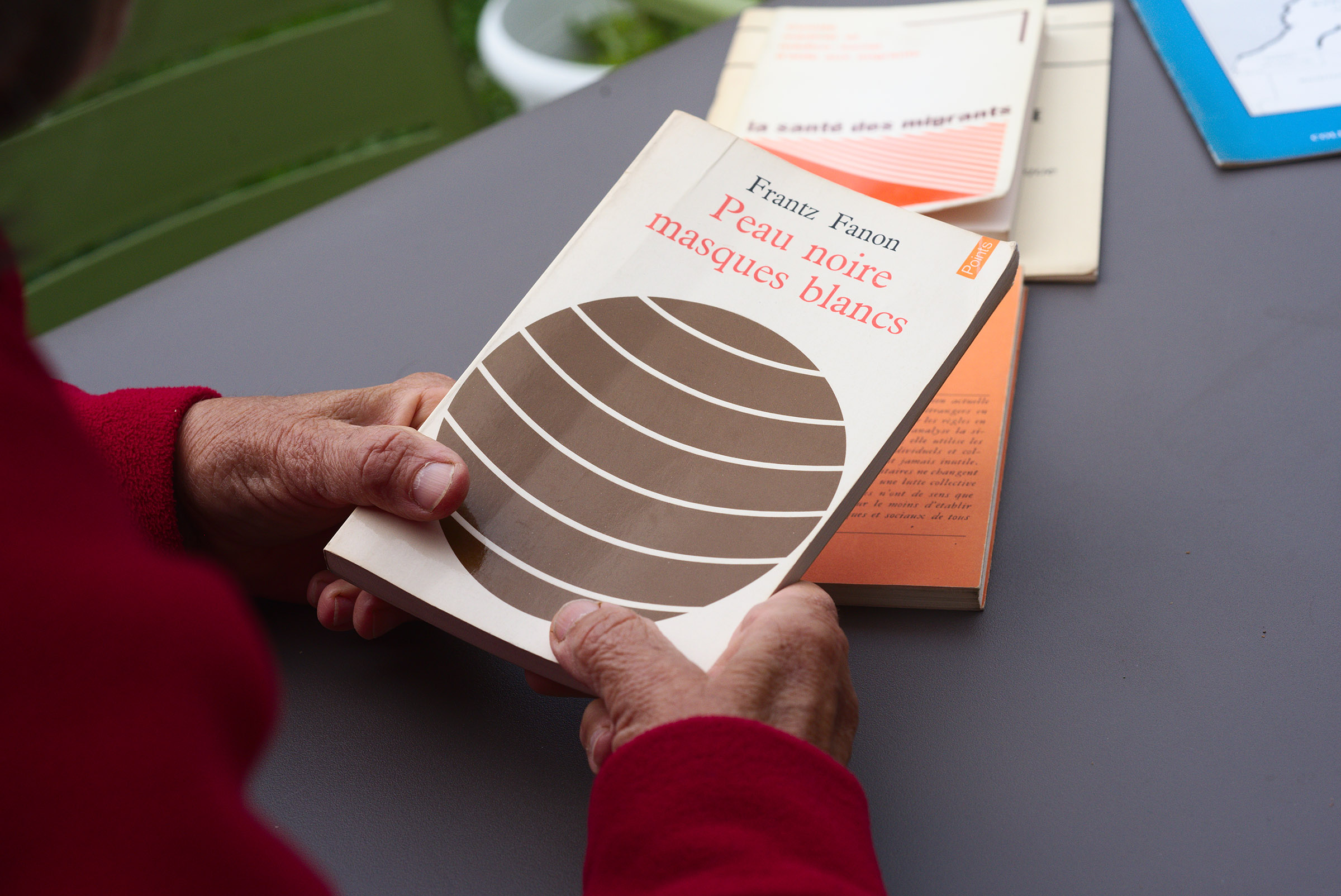

“My father called me an ‘unconditional fan of the Arabs’, although I had never met any Arab before I began my studies to become a social worker in 1969. Studying has been a huge opening onto the world, it was fantastic. I was passionate about law and sociology. Many other students had had other professional experiences before and it was very enriching to be with people who had lived more than me. At the time, social services worked a lot with migrant workers and families from Portugal, Spain and later the Maghreb. I did a study on migrant workers’ living conditions in hostels. I met a researcher from Tizi Ouzou, who was one of our lecturers. He gave us a very different vision of the Maghreb, far from the usual scorn and ignorance of ‘the Arabs’ that were commonplace in France at the time.”

“During the 70’s, I traveled to Paris a few times with my best friend Marie-Thérèse. She looked for music, I looked for books. When I began to work, I also spent time in a bookstore in Bourg-en-Bresse, where I would go regularly for meetings and training. You could spend hours there, seating and reading. I was looking for books on Algeria, Palestine, migration: these were my topics. Nobody advised me, and there was no Internet at the time to help you look for things. I stumbled on books by chance.”

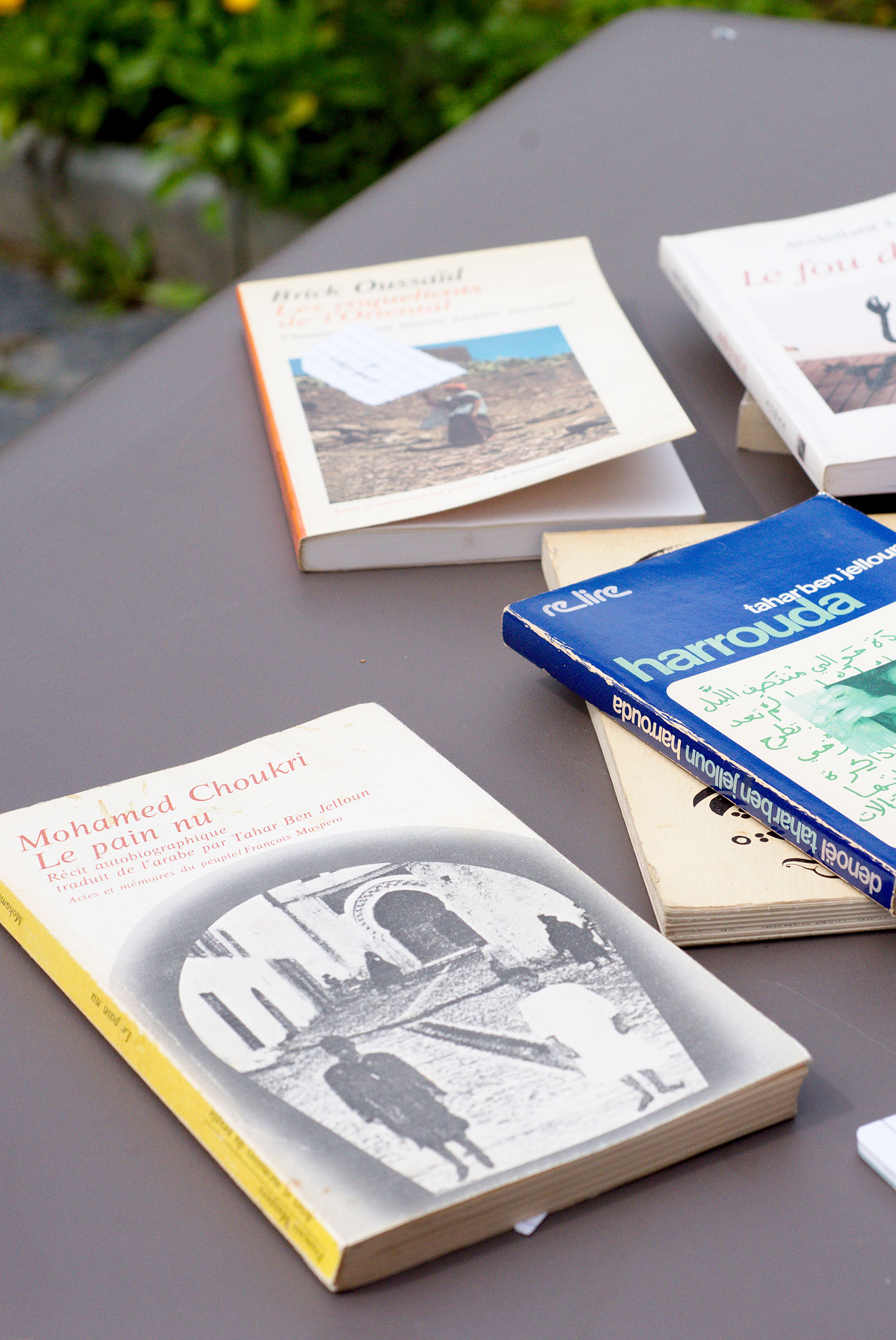

“I got interested in Morocco after I met Abdallah. At the time, for people like me who contested the French government’s line, Morocco was a bête noire, because of the king and all that. I was very conscious of this before I met Abdallah, although I did not expect to live it in person… So, I was interested in Moroccan dissidents. This is why I have many books by Tahar Ben Jelloun from the late 70’s. He was already very famous in France.”

![*Hospitalité Française* [French Hospitality] was written in 1983 in reaction to the murder of Toufik$$Ouanes, a 9-year old boy who was shot by his neighbour because he played with firecrackers in a suburban housing estate in La$$Courneuve. This event contributed to the emergence of a structured anti-racist movement in France. An edited version of the book was published in 1997, subtitled *Racism and Immigration from the Maghreb*. Image:$$Ouidade$$Soussi$$Chiadmi.](https://qalqalah.org/media/pages/notes-sur/notes-sur-la-bibliotheque-de-chantal-soussi-chiadmi/845724822-1600262022/osc_5361.jpg)

“I was very interested in authors from the Maghreb. I read the ones who wrote in French, because they were educated in French before the independences. Or the ones who were translated from Arabic to French. Abdellatif Laâbi was a great discovery for me. He is very special to me, because of our family’s history. He was imprisoned for more than 10 years, as an opponent to Hassan II, the king of Morocco. He was married to a French woman, a teacher, who always supported him while he was in prison. They wrote children books together. Well, he is a true character, a true poet, with a free mind. There are people, like him, whose perseverance strikes you. I don’t read much poetry, but he wrote novels and reality books that are very interesting.”

“Le pain nu was given to us as a present by my brother in 1980, when Abdallah arrived in France. Abdallah read it in Arabic. He does not like this book because it reminds him too much of his childhood’s living conditions. The novel itself does not shock him. He could have written pretty much the same story. He grew up in the countryside, but when his family moved to town, when he was 10 years old, it was really misery. What he does not like, is that French people talk about the book and say: ‘You see, living conditions in Morocco…’ It is not their story, it is his. Stressing the problems is a bit like voyeurism, you see? He does not like this.”

“I do not know classical literature very well. If I had to talk with people from the good society, with a proper education, there are many things I would not know… There were no books at home when I was a child. There was an atlas, and that’s it. My parents did not teach us literature. I could tell you a lot about children who were not able to enjoy school as much as others because they did not receive an opening to literature or to knowledge from the start. For example, we did not talk about art, we did not know about it. Although my aunts, my mother’s sisters, they went to high school. My aunt Gisèle was a teacher. They do read. But they are younger than my mother. My mother did not like reading books. And I think that she did not have the time when she was young, and once she became older, she did not want it anymore. Anyway, I arrived to high school with nothing.”

“Slavery, racism and Islam became some of my main interest points. I read many books by Abdennour Bidar. He is a French philosopher who wrote a lot about Islam. His mother was a doctor in France and she converted to Islam, it is a very special trajectory. He writes about spiritual Islam, how to adjust to civilization, how to live with Islam in France. He is very open, he tries to popularize things, to touch people. Recently he was invited on TV a lot, to talk about terrorist events. Before that, you only heard him on the radio.”

“I do not consider myself a feminist, but I find that women face so many inequalities! Around me, women have always been the pillars of family and I think that they are of utmost importance for families’ balance and children’s education. And yet, their fate is so unequal! I say that egality will never come, because women bear children and that is a constraint that needs to be taken into account. But then women should receive help, and support, and understanding. Yes, I would fight for that.

In my work, I was primarily interested in women and their condition. When people live in normal conditions, with a relatively normal material situation and interesting jobs, women already have a lot to bear. But in disorganized contexts, without money, their problems multiply. Or when women find themselves alone, when the children’s father is gone. I was very busy with that. I followed many women who were addicted to alcohol. Generally, everything at home relies on a woman’s shoulder, so the consequences of her alcoholism can be dramatic. And problems of domestic violence. And addiction to drugs. That was more towards the end of my career. Today, I think less about all this. I have been retired for 8 years. I am losing the ties to my former job.”

“I would not be able to read a book in Arabic. I can read the letters, but not the words. It is one of my greatest regrets. It would have required more time, and support. Abdallah told me that I could never speak Arabic. It is true that I do not have an ear for language. I never pronounced it properly. But when I go to Morocco, I am more at ease. My nieces there helped me a lot, I am very grateful to them. They are the ones who taught me. I would like to get back to it, now that I have more time. Next Fall, I have two things to go back to: the swimming-pool, and Arabic!”