Virginie and Victorine met Vir in July 2019, during the workshop Qalqalah: Thinking about History, which they organized at the Centre Régional d’Art contemporain Occitanie à Sète. Vir was introduced as a participant in the workshop by the École supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Montpellier, from which he had graduated a few years before. Prior to the workshop, Vir (currently a PhD candidate at Le Fresnoy and l’Université du Québec à Montréal, wrote to us: “I realize that my research interests often lead me to solitude. Unfortunately, very few of my academic peers share my decolonial-linguistic-videotic concerns. Qalqalah قلقلة appears like a shooting star and I do not wish to miss that encounter.” On the last day of the workshop, we invited every participant to introduce their work around a potluck of tomatoes, watermelon and fried seafood. Before speaking, Vir dressed himself with a tunic adorned with hand-made, embroidered flowers by Mayas-Tzotzil, an indigenous people from Zinacantan, Mexico. These embroideries have become a sign of belonging and recognition, although they had initially been imposed by the Spanish colonizers in order to distinguish between the different communities. Vir, suddenly transfigured into a daylight storyteller, and told us about his research on Afro-mexican histories (interlaced with his own grandfather’s story) and his attempt at learning Nahuatl, an indigenous language used by the Aztecs, and that his grandmother spoke. Family stories and political issues were interwoven through their relationship with languages — a feature/particularity that went straight to

Qalqalah قلقلة‘s heart.

We thus stayed in contact during the following months. At the time, we were preparing the exhibition Qalqalah قلقلة : plus d’une langue for the CRAC, and we invited Vir to present his film Piramidal, in dialogue with an installation by Lebanese artist Mounira Al Solh, Sama’/Ma’as — seven textile pieces embroidered with Arabic anagrams. As he explains below, Piramidal reactivates Aljamiado, a mode of writing Spanish texts into Arabic alphabet, used in Andalusia prior to the Reconquista.The film thus connects Mexico with Arabic-speaking populations who used to occupy Southern Spain, questioning the obliteration of Al-Andalus’ heritage in the colonial history of Central America.

There were obvious affinities between Vir’s research and Qalqalah قلقلة ‘s preoccupations, and we thus invited him to join our Editorial committee together with Line Ajan and, later, Montasser Drissi. At the same time, we invited him to narrate the hybrid genesis of his film, Piramidal, under the form of an essay. According to feminist, Cuban-American anthropologist Ruth Behar, an essay is an act of witnessing, which navigates between the description of an object and the inscription of a subject. “An amorphous, open-ended, even rebellious genre that desecrates the boundaries between self and other”, the essay allows the researcher to “fulfill those illicit desires” of writing poetry, fiction, drama, “anything but ethnography” or, in our case, art criticism 1. Vir’s text, which we received as a gift, is a magnifikhoo example of that. From the streets of Mexico to Marseille’s Kasbah via the decrepit lecture halls of Montpellier’s university, it intertwines the author’s contemporary dreams with those of a baroque Latina poet and other living characters and active ghosts, who populate religious rituals, popular songs, and a history of decolonial, anti-imperialist struggles that proliferate on both sides of the Atlantic.

Both the film Piramidal and the essay below tenderly nurture “heterolingual imaginaries”, to borrow the terms of Myriam Suchet, another companion of Qalqalah قلقلة. In the original version, Spanish and Arabic words are interspersed with Vir’s recalcitrant French, for which he claims imperfection as if it were a Creole. En passant, he reminds us that tongues are also made for kissing. When we edited the French version of his text, we kept our interventions minimal, in order to preserve the echo of his jalapeno-pepper accent, and the particular syntax that cripples the idea of language as a pure, homogenous or fixed entity. Vir himself translated his text into English, an English that playfully resonates with remnants of French grammatical structures, and other, deeper linguistic attachments. Thus the text you will read below also bears witness, in all its imperfections, to the author’s journey through multiple languages.

Arabic translation upcoming.

Pyramidal پيراميدال

Mexico City, 2008. I had been learning French in parallel to high school for three years. I would go back and forth between the educational services of the French Embassy and my hometown, Yauhquemehcan, a small town in the state of Tlaxcala. In the waiting hall, other young Mexicans who wished to study in France awaited. Most of them had studied in French schools either in Mexico City or Guadalajara, with the final goal of one day studying at a French university, thanks to the financial support of their families, predominantly wealthy. The educational coordinator who oversaw my application file quickly understood my situation: although I had gotten a low grade in the French test, I still wanted to study in France. She scrolled through hundreds of programs and pulled up the parameters that automatically sorted the results, until we were left with a convincing option: Arabic faculty at the University of Montpellier III. But be careful! she added. It is one of the lowest ranked universities in France. Nevermind, I reasoned to myself, even the worse French faculty would be better than any Mexican one. The coordinator continued: “You aren’t required to go there to take the exam.” To go where? “Pas tenu de”, what did that mean again? My impenetrable jalapeno-pepper accent was beginning to get on her nerves, but we eventually came to the conclusion that this was my only chance. Arabic language degree it shall be. Either way, I was leaving the country, and I was the happiest teenager while eating my pistachio macaroon in the posh and gentrified streets of Polanco.

Once installed in my university dorm, I did not have great difficulties going about my little student life. I had been living by myself since I was 14 years old, having also found a way to get out of my pueblo to go to Puebla, a 3-million people city at that time. Montpellier seemed small and welcoming, illuminated by the bright rays of a Mediterranean sun that was unknown to me, a child of volcanoes. How surprised was I when I arrived at my first Arabic language class: the classroom was just like the faculty, age-worn. The professor looked like an Indiana Jones sidekick, wearing an eggshell-white shirt, dark ocher pants, rolled up sleeves, and had a pair of blue eyes that contrasted with the hue of his tanned complexion. He looked like a time traveler who had just returned from the Sahara in the 1920s. As for the students, our names were Samia, Yacine, Mohamed, Fatma, Andrés, Tabata, Younès, and so on. My comrades were for the most part the children and grandchildren of those who, through the course of colonial history, had settled in France, a whole great story that, until then, I completely ignored. Some had grown up in Algeria, in Morocco, and were, or were not, of French nationality. Some were more or less familiar with the Arabic language, but in any case, I was falling behind, along with the other non-Arab student, Élodie.

As the whole course was based on the learning of Arabic, we had class three times a week, and so bonds of familiarity were weaved between us and our Professor, Mr. Petillot. As the year went by, I never managed to catch up with the rest of the class. Indeed, in order to learn Arabic, I first had to master the French language, which was far from being the case. I was impressed by the encounter with this French youth from an immigrant background, an unsuspected reality from the other side of the ocean where we were taught songs by Françoise Hardy and Barbara, pop French singers from the 60’s. Somehow, I was closer to the idealized image of France when I walked through the wealthy neighborhoods of Mexico City. Fatma became my first confidant, the one who answered all of my naïve and irritating questions. At the time, I was already trying to understand the situation of the Arabic-speaking minorities through the prism of our own experience as Mexicans and Mexican immigrants in North America. Although I should not stop at this comparison, it was fundamental to understand the place I was to occupy in the French landscape later.

My second companion was Yacine. He was born in Marseille, but his parents lived in Algiers. His look reminded me of Mexican boys, with a slightly unbuttoned white shirt, black shiny shoes, pressed trousers, and hair gel. I guess he liked me, among other things because he was muddling through his learning of Spanish and he liked singing along “El mariachi” interpreted by Salma Hayek and Antonio Banderas. During the Día de Muertos holidays, he invited me to visit Marseille with him. Yacine, his brother, Ismaël, his sister-in-law, Delphine, their son, Farès and I drove all the way to Marseille. It had a feeling of déjà-vu to me, with the port that reminded me of Veracruz; but what Yacine wanted to show me was the Kasbah of Marseille, as he called the Noailles neighborhood. We walked the narrow streets of Noailles and Belsunce until we found the restaurant that Ismaël was trying to make me discover, an Algerian bistro serving chorba every Sunday, which was going to make up for my lack of capsaicin, they said.

I invited Yacine home to drink a bottle of mescal as a gesture of gratitude for taking me to Marseille. When we laid down side by side, after the exhaustion induced by a raï-mariachi evening, he asked me: “Are you a fag? Am I what? I replied. “Don’t you know what a fag is?” he asked, bringing his face closer to mine. “No, I don’t.” We both caressed each other while he whispered words to me in Arabic. I asked him to translate, but he said: “No way, I can’t tell you that in French.” I presume that the first words of love addressed to me since my arrival in France were pronounced in Arabic.

I learned to write in Arabic, but I never managed to understand it — although I continued to follow the lyrics to Ziad Rahbani or Souad Massi’s songs to the letter. In order not to forget this skill, I trained myself to write texts in Spanish while using Arabic characters. Impressions of the day, sometimes just words in French — although the exercise from Spanish to Arabic looked a little simpler, because every single letter is pronounced. If I had to rewrite French words in Arabic letters/characters, how should I write the word “magnifique”? Its Spanish version, “magnifico”, is much clearer when written in Arabic. Actually, not that much, because in the end, the “oh” becomes a “hoo”: magnifikhoo.

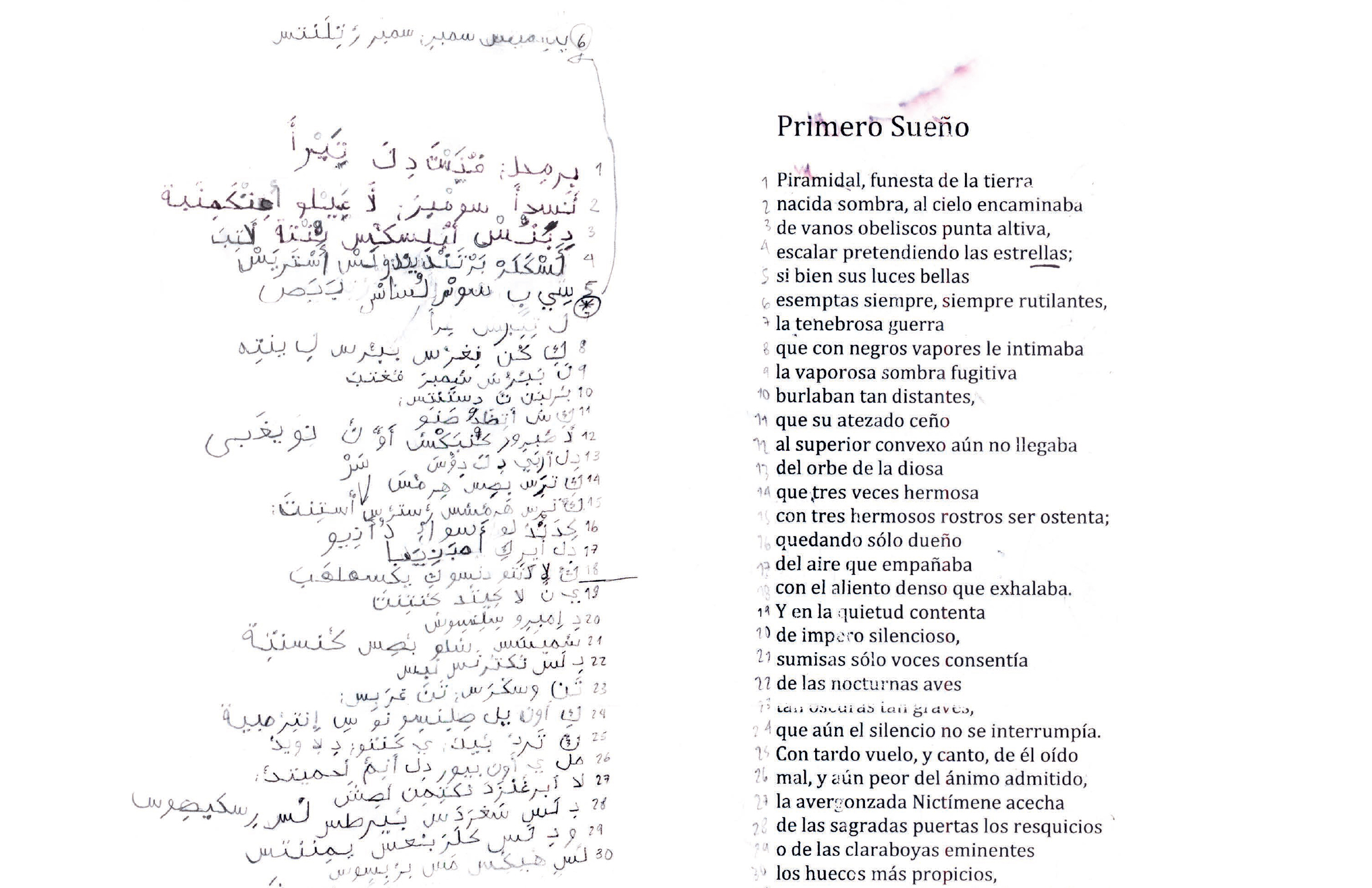

Primero Sueño [first dream], by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, a Mexican poet of the 17th century, is one of the golden age of Hispanic literature’s pillars. It is a mysterious text, whose meaning resists even the most erudite of minds. Fascinated by its linguistic profusion, I had the idea of transcribing all of its verses into Arabic characters. I said to myself that the phonetic translation of the poem’s enigmatic words would bring me back to a sort of magical spell or incantation. It could give me access to sounds and a musicality quite impossible to experience for someone exclusively navigating throughout one’s language – for instance these words rarely used in Spanish that are: altiva, pavorosa or longas, الطيبا, پابوروسا, لونغاس. Indeed, although Sor Juana mastered Spanish better than anyone in her day, she grew up speaking Nahuatl, the “Aztec” language, as well as Latin and the Afro-Mexican-creole variety of Spanish, which is the reason why, in my opinion, she had an external point of view regarding the use and sonority of Spanish.

Pyramidal, funest, پيراميدال فونيستا… Thus begins the labyrinthine universe elaborated by Sor Juana along the 975 verses of Primero Sueño پريميرو سوينيو. The poem is inhabited by animals, objects and monuments (pyramids, obelisks) that narrate the journey of Sor Juana’s soul, observing and discovering the world. In the midst of her dream, her spirit visits both the old (Europe, Mesopotamia, Egypt) and “new” worlds, and portrays a dreamlike and surreal universe where everything happens: the senses succumb to the wavering of the night swell; the mysterious sounds are surrounded by the mythical magic of stimulating poems. In 2015, I did an artist residency at Casa de Velásquez in Madrid, whose mission is to develop creative activities and research related to the arts, languages, literatures and societies of Iberian, Iberian-American and the Arab Maghreb countries. During my stay, I met Marianne Brisville, a historian colleague and specialist in medieval Maghrebi cuisine, who, after watching the transcription of Primero Sueño in Arabic characters, taught me about Aljamiado, a disappeared linguistic variant.

Aljamiado was a Spanish dialect, written in Arabic characters. It was spoken by the ancient inhabitants of Al-Andalus who mastered Arabic and Spanish, and who used it to communicate in secret. Thus, for those who only spoke Arabic, these texts were readable yet their meaning remained obscure, while Spanish speakers simply could not read them. With the ousting of the Arabic-speaking communities from the peninsula in 1609, this mode of writing perished. The Arab populations were expelled from the peninsula in the 17th century, but many had already settled in Latin America, in Spanish-controlled territories, such as Mexico or Colombia. In short, a good part of the first colonizers were the direct descendants of the Arabic-speaking inhabitants of Al-Andalus.

In the 17th century, the Spanish Empire used its “eraser” — a metaphor by Mexican writer Carmen Boullosa — to erase the traces of the indigenous peoples of Abya Yala2 on one side of the ocean, and to eliminate the traces of Arabic history on the other side, in the Iberian Peninsula. In view of these considerations, the Spanish golden century does not properly highlight the contribution of Mexican, Colombian or Peruvian writers, including Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

It may seem fortuitous, but Sor Juana’s family history goes back to her maternal grandparents, Pedro Ramírez de Santillana and Beatriz Rendón, who came from Andalusia and who settled in Yecapixtla, an indigenous village at the foothill of volcanoes, in Mexico.

In the solitude of a pre-Hispanic Mexico, which at the time was fading away and giving way to the “new world”, the Soul of Sor Juana was confined between the four walls of her convent cell. To me, it did not seem impossible to imagine her dialoguing with memories of the old worlds — including the Al-Andalus of her ancestors, as she mentions in her Primero Sueño.

My project for Casa de Velázquez focused on botanical expeditions led by the Spanish crown to New Spain and New Granada, present-day Mexico and Colombia. It questioned the empire’s desire to impose a Latin taxonomy on a world with a cosmogony unmastered by the colonizers. Some of the documents I studied are kept in the General Archive of the Indies in Seville (Archivo General de Indias), where the most important collections on the political, economic, cultural and social history of the old Spanish colonial empire are stored. Visiting this mausoleum reminded me of the empire’s historical will to glorify the prowess of the invasions, pinned right at the core of one of Al-Andalus’ former political capitals.

I went to Andalusia as a documentarist, trying to spot what was left of the Arab presence on this territory. I found traces in the baroque costumes and festivities of the Holy Week, which I was delighted to film, but the language was missing. I remembered the Primero Sueño, which I had, without knowing, transformed into an Aljamiado. I then asked two Arabic-speakers to interpret the transliterated poem: first, an Algerian gentleman whom I met during a stay in Toulouse, then my friend Anhar Salem from Saudi Arabia. In the process of recording the transcript, it was interesting to hear the difference between the pronunciation of a speaker from the Arabian Peninsula and one from the Maghreb. Indeed, I tried to transform the Spanish sounds so that they would be readable by an Arabic-speaker, in particular the “eh” and the “oh”, as well as certain consonants like the “qu”, the “gu” and the “c”, “z”, and “s” (in Mexico we do not pronounce the “z” sound as in Spain). This transformation had an impact on the way the two struggled to find a “correct” pronunciation. One does not read characters, but words; without the meaning of the words, the exercise of reading a text in Aljamiado turned out to be a true cerebral and physical performance (of their vocal cords). Anhar told me that, for her, these enigmatic words, which did not mean anything in Arabic at first glance, resembled, in their spelling, some words she used in her Arabic. I could see the same mental process with the Algerian sir, as if the words of this Aljamiado were trying to disguise themselves into Arabic words to find a unique rhythm in everyone’s mouth.

From this long, unpredictable journey that led me from Mexico to France and Andalusia, through the Arabic language and the poems of Sor Juana, a film emerged: Piramidal پيراميدال, associating the images of the festivities of the Holy Week with the recording of the poem. It is structured in three chapters. The first one features images filmed in slow motion (96 frames per second), showing tronos, heavy wooden floats carrying Madonnas and Saints. The reluctant cadence of voices follows the slowness of these religious symbols, which seem to have just emerged from other eras. In the second chapter, a lot of virile men parade wearing masks often representing female biblical characters in tears. Freeze-frame shots reveal the faces behind the masks; the flowers, the gilding and the bare feet on the asphalt remind us of the solemn and luxuriant character of this celebration. In the last chapter, voices fall silent, replaced by a montage of music found on site, the faces of the sevillanas, these women who are beautifully dressed in black and gold; gold in the crowns of the virgin Mary, in the gleam of candles that throw their wax on passersby, gold in ladies’ hair-presses, in the gilded woods: these elements transport me to an energy that Sor Juana must have been familiar with.

The Spanish language, in the splendor of its imperial ambition, hides communication vectors with other cosmologies and other languages, such as Nahuatl, Quechua or Guarani, and if we dig a little deeper, it hides other secrets, such as Aljamiado. The Catholic Holy Week has always been a magical ritual for me: as a child, I forced my mother to stay awake in order to attend the night processions moving from village to village, while reading the bible as one reads a spell book. These processions are like a mole, this Mexican dish with heterogeneous components, whose ingredients allow us to make a wish. As for me, I no longer wish to resuscitate the Christ. In the darkness and opacity of this baroque night, I seek to show this shadow play, where the echoes of forgotten languages are juxtaposed next to each other. If imperialist languages, such as Spanish or French, are immense locked-up palaces that prevent access to other epistemologies, the rediscovery of Aljamiado can thus be seen as a dormer window, among many others, from which we can create possible bounds with those who are confined in other building dormers.