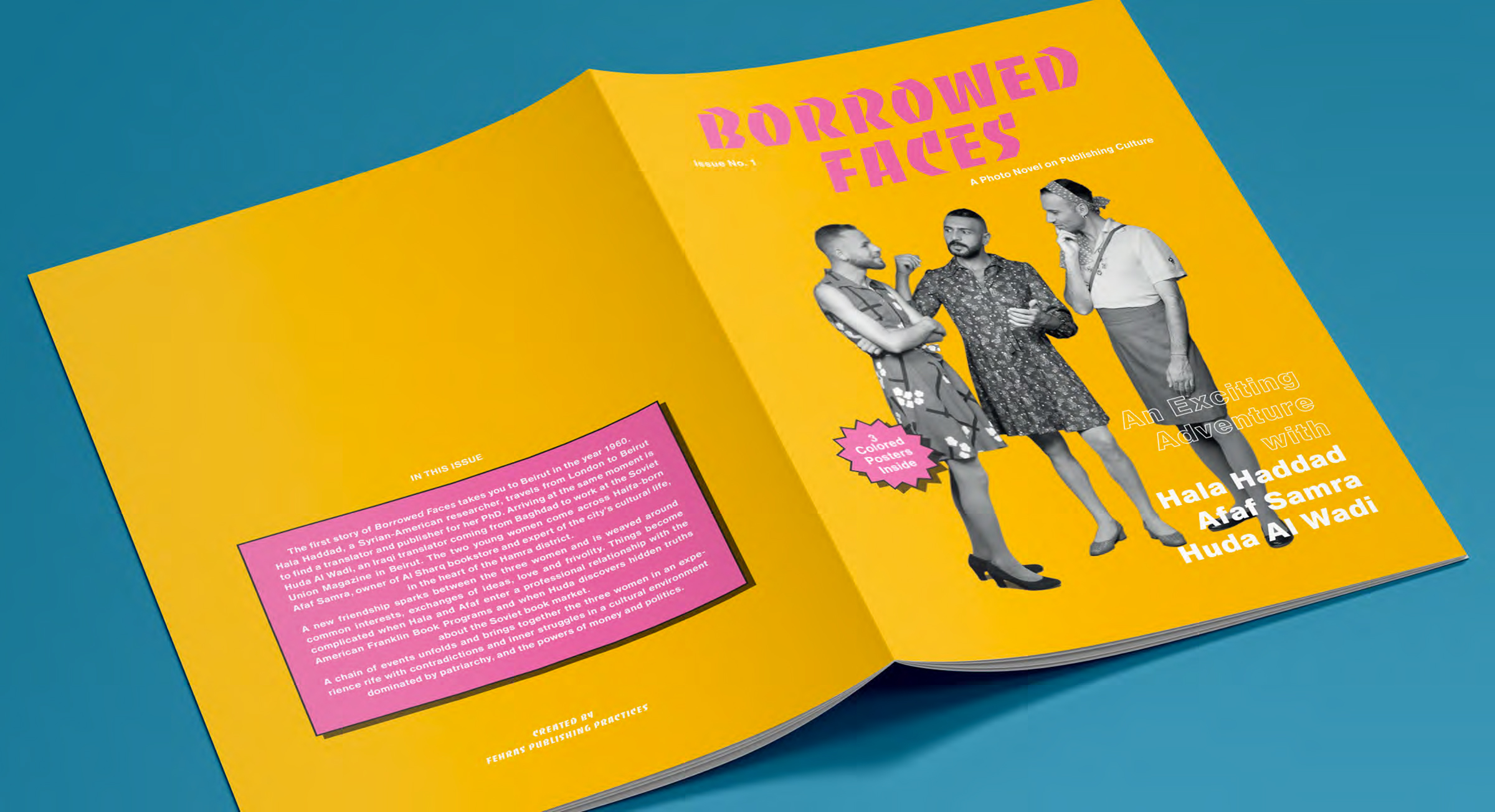

In this text, dear readers, we’re taking you on an archival research journey that we at Fehras Publishing Practices undertook over the last two years between Beirut, Damascus, and Berlin. It’s a journey through which we delved into Middle Eastern and North African microcosms of the Cold War and their cultural life during the 1950s and 60s. The following lines will tell you stories of figures whose tracks we followed, and of global institutions that — either openly or covertly — supported cultural projects that served their policies. We’ll take you behind the scenes to publishing houses and publications that were produced individually or collectively in either a drive for change or under the influence of the political ideologies of their owners. Some of these projects eventually came to an end, while others were destined to live on.

Our interest in examining cultural practices during the Cold War developed through discussions in which we came to believe there existed common denominators between cultural practices then and today. These commonalities are particularly striking if we consider how this era witnessed the dawn of the globalization of culture in the Arab region, which had become entwined in international networks of political capital, whether personal, public, regional, or global. This period also saw the movement of intellectuals between countries in various regional and international contexts, which led us to question their autonomy when under the pressure of endeavours seeking cultural hegemony. We wanted to understand the dynamics of these intellectuals’ movements between the centers of a bipolar world order.

The Cold War era was among the most fertile and critical periods in the history of Arab culture and publishing because it entangled politics with cultural production. World War II had drawn to an end, and some Arab countries had achieved independence while new Arab regimes had seized power. These changes aligned sharply with a range of ideologies — communism and Marxism, leftist liberalism, Syrian or pan-Arab nationalism, Nasserism and Baathism — that indelibly marked Arab culture and publishing. The rivals in the bipolar world order, the United States and the Soviet Union, each pursued policies of cultural and intellectual hegemony that implicated international politics in cultural and publishing practices. In this bipolar order, each superpower established institutions and funded a network of international endeavours, making the Middle East and North Africa integral to the cultural Cold War.

As these changes unfurled, Arab cultural production and publishing was transforming radically from within: new literary styles and ideas emerged during this period. Some were influenced by trends in Western philosophy, such as realism, which adopted the idea of iltizam, or literary commitment and the notion of art in the service of society, while modernist intellectuals became concerned with the self and with literature for literature’s sake. At the core of these movements were publishers, writers, poets, and translators, some of whom established collectives and regularly held seminars, or who launched initiatives, publications, publishing houses, and other institutions. These figures maneuvered between international foundations and publishing houses espousing oppositional politics, drawing them together in a web of collaboration, of friendship and love, as well as fallings-out over politics and the public role of the intellectual.

Pursuing these lines of inquiry, we dug into print archives from the 1950s and 60s, such as books, magazines, memoirs, personal letters, newspaper articles, and images. This research was the extension of another project we undertook in recent years to document the library of the late novelist Abdul Rahman Munif. Belonging to an Arab intellectual such as Munif, its contents provided us with new and valuable information about the history of publishing practices in various periods, and we learned much from the many gems in his Damascus library. Our research approach was further refined during our visit to Beirut in early 2018 and our return there in July 2019 to complete our research.

It was an arduous task to find information: there is no catalogued archive of publishing in the Middle East and North Africa, and numerous publications, magazines, and publishing houses have disappeared, just as many of the era’s figures have passed away. To move around these challenges, we chose to base our research on meeting booksellers and archivists in Beirut and Damascus, followed by careful research in the archives of universities, institutes, and cultural foundations. We further interviewed Cold War specialists and primary sources who had been contemporary to the period.

Soviet publishing between propaganda, erudition, and translation

We began deep in the crowded streets of Beirut’s Hamra neighborhood, at Al-Furat for Publishing and Distribution (Euphrates), an exceptional place owned by the archivist and publisher Aboudi Abo Jawde. During our very first encounter with him, Aboudi’s rich archive opened up to us new and unexpected directions of research. Upon the mention of any obscure publication, publisher, or book, he would disappear for a few moments to return with archival materials and a smile on his face. Contrary to the reputation of most collectors, Aboudi unreservedly opens his space and archive to researchers.

Aboudi was our means to accessing rare publications such as Soviet Union, a monthly social and political illustrated magazine that falls into the category of propaganda media. It was launched in 1930 by Maxim Gorky in Moscow, and was published in 19 languages including Arabic. Soviet Union was distributed in most Arab countries, and subscriptions were advertised in right-leaning Arabic magazines such as Al-Tarik Magazine in Beirut and Orient Magazine in Cairo. Accessing Aboudi’s collection of Soviet Union and gaining exposure to its cultural discourse helped us to understand Soviet propaganda policy and its adaptation to the changing circumstances of the Cold War.

The local distribution network of Progress Publishers led us to Al-Zahra Modern Bookstore in Damascus, the authorized representative for importing Soviet books, and one of the main suppliers of Progress Publishers. During a tour of Damascus bookstores in 2018, however, we found it out of business and its archives liquidated. The story of a bookstore that had sold Soviet books even decades after the Soviet Union’s collapse had thus been brought to an end.

Yet our understanding of Progress Publishers and Soviet publishing sharpened following our visit to the library of the Russian Cultural Center in the Verdun neighborhood of Beirut. We entered hopeful of finding Progress Publishers books. It was a big surprise to find a large section of Progress Publishers publications from various eras and until its closure in 1991. Within seconds we became beehive workers, spreading out between the library shelves to photograph and document the covers of books relevant to our research, and selecting specific books we very nicely tried to convince the librarian that we needed to scan.

In following the Soviet influences on Arab thought and publishing, we took pause upon discovering the financial role played by Progress Publishers in supporting a number of local publishing houses. These local publishers imported books from the Soviet Union at trifling costs and then sold them at higher prices, using the income to support their own publications. One of these publishing houses was Farabi Publisher, which opened in Beirut in 1954. It published numerous Marxist, communist, and socialist publications that were significantly influential on the Arab Left. In an interview with Ghazi Berro, one of its former directors, he told us that the publishing house had received huge quantities of Soviet publications at insignificant prices or even for free, and then sold them, forming a financial resource that contributed to supporting the publication of local leftist writings or the translation of Western texts.

While searching for publishing houses that distributed Soviet books, new questions arose about translation. Who were the translators of those literary and political works that influenced the Arab Left? This encouraged us to focus on a new factor in our research, one outside the context of institutions and publishing houses: the personal trajectory of translators who either actively participated in this cultural life or who lived in its shadow. We divided translators into two generations, the first working up until the 1950s and including individuals who were driven by their personal convictions and values to translate communist books and Russian literature. They translated Russian works via pivot languages such as French and English, meaning the colonial languages of that time, and the Arabic book market was filled with translations of Russian titles that were widely popular in the West. Russian texts published in Arabic at that time were thus tied to European taste for Russian literature.

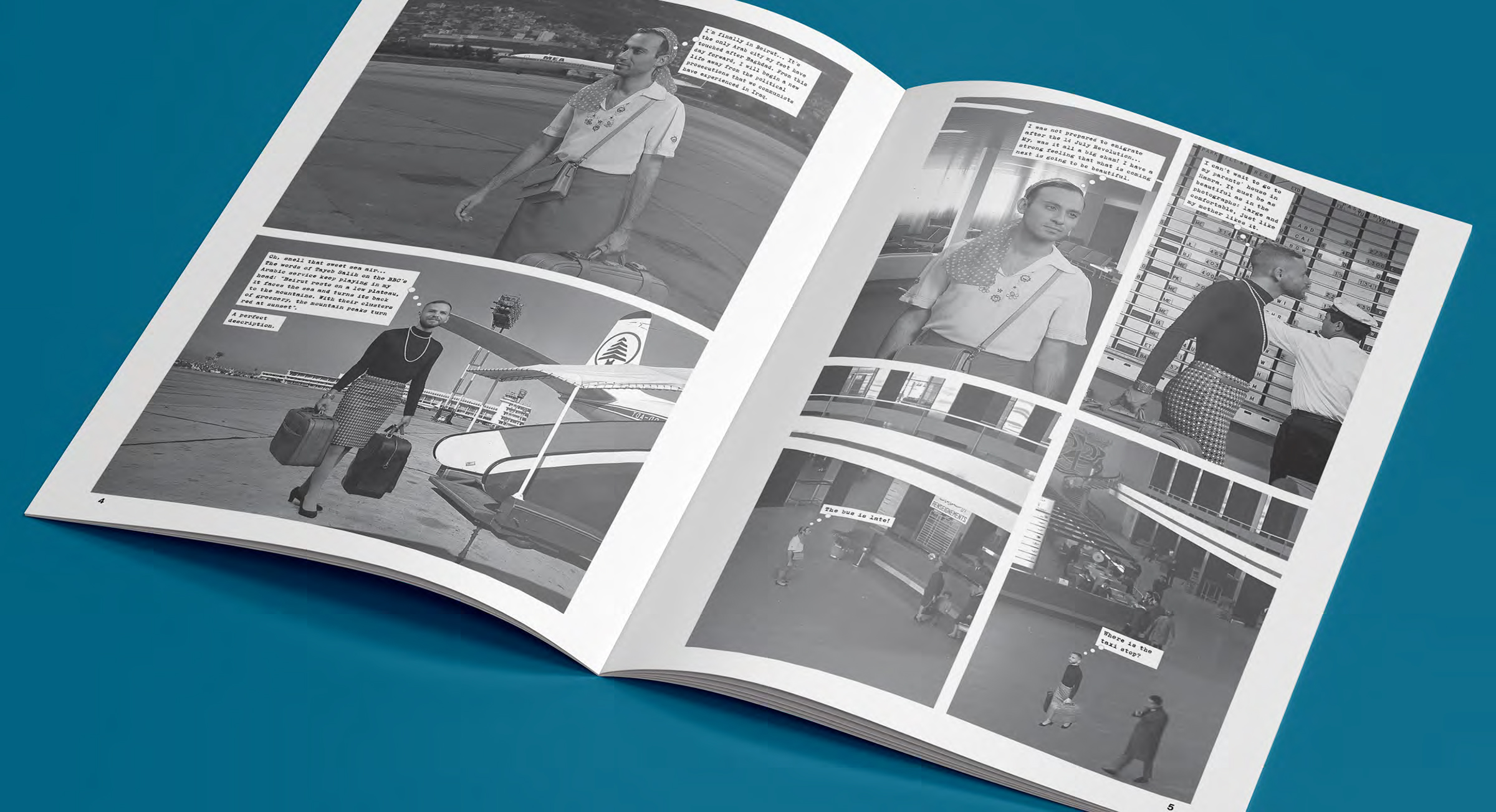

As for the second generation of translators, they were communists from Iraq and Syria who had been persecuted for their political convictions. Among them was Mawahib Kayali, who took part in 1951 in establishing the Syrian Writers Association, which upheld the ideal of committed literature that advanced society, and which favored realism. Mawahib was imprisoned in 1958, when the United Arab Republic’s authorities undertook an arrest campaign of communists. Following his release he left to Moscow, where he joined the team of Progress Publishers translators. Also noteable from this generation was Ghaeb Tumah Farman, who wrote short stories influenced by the communist movement in 1950s Iraq and published them in cultural magazines. He was forced to leave Baghdad in 1960 to escape the repression of Iraqi president Abd Al-Karim Qassem, and arrived in Moscow to work for Progress Publishers. Ghaeb introduced a new generation of Soviet writing to Arab readers, translating directly from Russian to Arabic without a pivot language. While the first generation of translators of Soviet books had been led by individuals, this second generation was characterized by its affiliation with institutions.

The West and publishing in disguise

At first glance it appears that the cultural strategies followed by the United States during the Cold War were similar to those of the Soviet Union, in that it produced propaganda publications. The press division of the United States Information Agency produced Al Majal (Horizons) magazine, which was similar in size, style, and content to its counterpart the Soviet Union. Al Majal was published with the aim of strengthening understanding and friendship between the people of the United States and the peoples of Arab countries. Its pages depicted features of the highly developed life led in America, as well as the USA’s achievements in science, outer space, and art.

The luxury and happiness that the magazine depicted of America was not sufficient to convince the Arab peoples of capitalism, however, particularly in an era replete with political and armed struggles, and the forced dispersion and defeat of Arabs. The Americans had to create a new model that would allow entry to the core of the Arab cultural elite and subsequently to the general public. This model was embodied in Franklin Book Programs. While documenting the library of Abdul Rahman Munif, we found many books published by Franklin, for this institution’s publications had succeeded in occupying a large space in the libraries of Arab intellectuals. It was founded in New York in 1952 and its publications were distributed worldwide in what is known today as the Global South, from Indonesia to Iran to parts of the Arab world to Latin America.

The luxury and happiness that the magazine depicted of America was not sufficient to convince the Arab peoples of capitalism, however, particularly in an era replete with political and armed struggles, and the forced dispersion and defeat of Arabs. The Americans had to create a new model that would allow entry to the core of the Arab cultural elite and subsequently to the general public. This model was embodied in Franklin Book Programs. While documenting the library of Abdul Rahman Munif, we found many books published by Franklin, for this institution’s publications had succeeded in occupying a large space in the libraries of Arab intellectuals. It was founded in New York in 1952 and its publications were distributed worldwide in what is known today as the Global South, from Indonesia to Iran to parts of the Arab world to Latin America.

Franklin’s strategy inspired us to look more deeply into its history and the individuals who worked with it in the region. Its first office was opened in Cairo in 1953 as part of the cultural exchange agreement between the Egyptian state and America. Its operations were overseen by Hassan Galal Al-Arousi, who was well known for his proximity to the Egyptian cultural scene in its entire spectrum, including its Islamist currents. Franklin followed a complex policy in its dealing with government censors and the press. Financially it drew in Egypt’s major publishing houses, and it worked with elite writers and translators, as well as leading university professors and the ministries of culture and education, to create a reassuring image of itself. Some leftist entities accused it of imperialism and of aggression toward the socialist regime in Egypt through presenting the “American model” in science, art, and administration. It was further accused of exploiting certain gaps in Egyptian society. Franklin published in Egypt in collaboration with a number of publishing houses, including Arab Nahda Publishers, Egyptian Nahda Bookstores, and the Anglo-Egyptian Bookstore.

Franklin’s Cairo office got involved in a long term project to publish the most extensive Arabic-language encyclopedia of the time. We learnt about this endeavour through archival material we collected about the philosophy professor and translator Zaki Naguib Mahmoud, who was its editor, and who had to resign from the project following harsh criticism from his leftist colleagues. The encyclopedia was eventually published in 1965 with support from the American Ford Foundation.

Franklin opened a Beirut office in 1957, directed by three Palestinians: translator and academic Muhammad Youssef Nijam as director, translator and novelist Samira Azzam, and translator Ihsan Abbas. In the 1960s this office became a space that brought together intellectuals, translators, and professors from the American University in Beirut. This Beirut office focused primarily on translation of contemporary American literature and books in literary criticism, and published in collaboration with a number of Beirut publishing houses, such as Dar Al-Thaqafa, Dar Maktabat Al-Hayat, and Al-Ahlia Foundation for Printing and Publishing.

Reading the memoirs of individuals contemporary to the period, it became clear that Franklin’s employees were authorized agents whose mission was to bring to one table good texts, large publishing houses, and excellent translators who were professors at the American University or London or Cambridge Universities. Such renowned names were expected to dispel suspicions of malicious aims that might be directed towards the American institution. Yet it must be acknowledged that the high fees paid by Franklin to translators also helped them to work on their own cultural endeavours.

In general, research on Franklin Book Programs proved difficult due to the dearth of statistics on its work and the omission of its name as a funding institution or partner publisher in most Arab bookstore catalogues and archives. The institution’s full archive is now the property of Princeton University and is available to researchers on an individual basis.

Cultural hegemony and the role of globalization in countering neutrality

Concurrent with the start of the Cold War was establishment of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an American institution that was active worldwide. In 1950 it was based in Paris following a huge conference in West Berlin that brought together intellectuals from Western states and America to defend cultural freedom from communism. The institution spread worldwide via its global offices, while it planned conferences, offered study grants, and published cultural magazines such as Encounter in England, Preuves in France, Der Monat in Germany, Tempo Presente in Italy, Mundo Novo in Latin America, Black Orpheus in Nigeria, Quest in India, and Hiwar in the Arab world, and which was published in Beirut. The institution never revealed the source of its funding until a series of articles were published in The New York Times in 1966 exposing its funding as coming from the Central Information Agency (CIA), which was a public scandal for the intellectuals of that period who worked for it.

The Congress for Cultural Freedom opened its first office in Beirut in 1954, followed by a Cairo office in 1959, and these two offices formed the headquarters for its work in the region. The cultural magazine Hiwar was one of the most important projects it worked on in the Arab region. We learnt about the various stages of developing this magazine through letters exchanged in the 1960s between John Hunt in Paris, Simon Jargy — the French Orientalist of Syrian origin and Asia operations manager of the institution, and Jamil Jabr, director of the Beirut office.

Our archival journey brought us to another project on the margins of the cultural war that took place in tandem with the publishing movements of the Soviet Union and the United States of America. This was the Afro-Asian Writers Association, which was launched in Tashkent in 1958 with support from the countries participating in the 1955 Bandung Conference and the addition of other recently independent African and Asian states. Influenced by liberation and the Non-alligned movement, the Afro-Asian Writers Association sought to strengthen the spirit of cooperation between the peoples of Africa and Asia. Its Permanent Bureau was initially established in Colombo, and its operations moved to Cairo in 1967 due to its geographic proximity to sub-Saharan Africa. This office continued to function until 1978, when it was moved to Beirut following the signing of the Camp David Accord.

Many Arab intellectuals whose names we encountered during this research were active in the association, such as Suhayl Idris, founder of Al-Adab magazine, the poets Nazik Al-Malaika, Adonis, and Badr Shakir Al-Sayyab, political writer Hussein Marwa, literary critic Ghali Shukri, and others.

The association called for bolstering publishing in African and Asian countries. In 1967 it launched Lotus magazine, headed by chief editor Yusuf Sibai in Cairo. Lotus was a quarterly originally published as Afro Asian Writings, until its sixth issue published in 1970, when its name was changed to Lotus. It published translations of contemporary African and Asian literature and was issued in two versions, one Arabic and the other English and French. The magazine was significant for its role in creating cultural relations between Asian writers and those from Africa in an opposition to colonialism and neo-colonialism. Despite the desire to avoid political alignment with either of the two poles of the Cold War, the Soviet Union succeeded in capturing the spirit of the association and financially supporting Lotus in cooperation with Egypt, the Democratic Republic of Germany, and India. It was discontinued upon the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and resumed publishing again years later.

Lotus was significant because it formed a new global cultural broker removed from the hegemonic political polls, and because it was a new space for cultural exchange between countries of the Global South, meaning in Africa, Latin America, and developing countries in Asia. Through its translations, the magazine contributed to a new cultural awakening to literary works not previously known in the Arab world, and especially contemporary African literature and poetry.

The Congress for Cultural Freedom closely monitored the activities of the Afro-Asian Writers Association as it became increasingly influential on Arab and African intellectuals. Concerned by the association’s growing popularity, in 1961 the Congress for Cultural Freedom held the Modern Arabic Literature Conference in Rome in cooperation with the Italian East Institute and Tempo Presente magazine. Elite writers and intellectuals from Arab states attended in their personal capacities, alongside Western writers, with the aim of discussing Arabic literature and the problems posed by Arab writers pendulating between classicism and modernism. The attendees recommended holding an international conference on contemporary Arabic literature and encouraging the establishment of writing residencies that would be supported by cultural organizations.

The conference’s lectures were documented in a book published in 1967, and which we found a copy of in the archives of the American University in Beirut. Through this book we learnt of conversations that took place behind the scenes, such as discussion of naming Jamal Ahmad, writer and Sudanese ambassador to the United Kingdom and Lebanon, as the cultural advisor to Hiwar, which confirms the organization’s growing interest in the African context. Following a series of discussions, Tawfiq Sayegh was selected as the editor-in-chief of Hiwar magazine.

In Beirut we had the luck to meet writer and researcher Mahmoud Chreih, an expert on the life of Tawfiq Sayegh who was granted Tawfiq’s memoirs by the Sayegh family. Together with Mahmoud Chreih we examined Tawfiq Sayegh’s detailed notes about the months prior to the publication of the magazine’s first issue. These notes helped us to understand the complexities of that period and their influence on the Lebanese cultural scene, such as the selection of the team, the invitation of friends and writers to participate, and the fees agreed upon, which were high in comparison to those of similar publications in the region.

Hiwar soon became one of the most important regional cultural publications and an important space for the development of contemporary Arabic literature and poetry, as well as a venue for new intellectual voices. Yet the magazine received scathing criticism in Arab circles. In Cairo it was considered a right-leaning magazine, while in conservative Arab countries it was seen as leftist. It was discontinued following the scandal of its CIA funding uncovered by The New York Times in 1966. Tawfiq Sayegh published a double issue (26/27) in March 1967 that announced it was closing down. The consequences of the scandal affected him personally and led him to move to America and teach in the University of California until he died four years later.

The archive of the Congress for Cultural Freedom is preserved in 500 numbered crates in the basement of the University of Chicago library. Through the university’s website one can obtain basic information about the contents of these crates, and researchers can view part of them, while the rest remain sealed until 2045.

Publications and domestic movements

This research wouldn’t be complete without considering the effect of domestic political currents of the 1950s that contributed to creating new awareness that in turn produced new literary forms highly expressive of their authors’ convictions about cultural change. The rise of Arab pan-nationalism in the 1950s and its adoption by many Arab intellectuals including writers, poets, and critics — due to their belief that the Arabs are united by one language and shared culture — contributed to forming a new language that stood in opposition to the division of Arabs. The Palestinian cause, the right of return, French colonialism, and the Algerian war were main concerns of the majority of the works of this literature.

These rising ideas found a place in the heart of Al-Adab magazine launched by Suhayl Idris in 1953, and which continued to be regularly published for over 60 years. The rise of Nasserism and the influence of the ideas of Jean-Paul Sartre on committed literature led Idris to produce the magazine, which became a platform offering pan-Arabist and anti-imperialist literature. The position of Al-Adab contributed to developing Arabic prose poetry and liberating it from rhyming stanzas, bringing together an elite group of Arab writers such as Nazik Al-Malaika from Iraq, Hussein Marwa from Lebanon, and literary critic Ghali Shukri from Egypt. It also published the works of Ghaeb Tumah Farman, mentioned above, among others.

The political activity of the intellectuals involved with Al-Adab made its issues a mirror reflecting the region’s political and cultural history. It’s no surprise that some of its writers participated in the Afro-Asian Writers Association, which was an appropriate space for widening their horizons and thought through attending its conferences and working in its regional offices. Suhayl Idris participated for years in the editorial committee of Lotus magazine published by the Afro-Asian Writers Association. We encountered great difficulty in obtaining issues of Al-Adab in markets, for its importance has made it a treasure for institutions such as universities and libraries in the Arab Gulf, as well as for archivists. Ultimately we managed to access a collection of issues in the Orient-Institut Beirut, plus the publication’s website provides access to its entire archive.

Only meters away in Beirut is the site where features of a new modernist current in poetry began to manifest, led by Yusuf Al-Khal, a Syrian poet and translator and founder of Shi‘ir (Poetry) magazine. Established in 1957 and publishing 44 issues, Shi‘ir espoused self-oppositional critique, meaning literature concerned with itself. It was a space for modern Arabic poetry and translated poetry, for criticism, short stories, and domestic and international literary reports.

Shi‘ir transformed from a personal endeavour into a collective work and became a modernist phenomenon in Arab culture. It brought together writers such as the poet Adonis, the translator and critic Khalida Said, the poet and critic Salma Khadra Jayyusi — who translated into Arabic important works from contemporary American literature, Riyad Najib Rayyis — a journalist and later secretary of Hiwar magazine, and the Palestinian novelist and translator Jabra Ibrahim Jabra.

Other related endeavours appeared alongside Shi‘ir magazine. A publishing house also called Shi‘ir was opened and published translations and books in literary criticism. The Khamis Shi‘ir group (Thursday Poetry Encounters) met regularly in the 1960s and included a number of Arab modernist poets and writers. The continuation of Shi‘ir magazine was dependent on self-funding and the fees of reader subscriptions, and it was forced to close down in the late 1960s due to limited funds and the scathing criticism directed towards its members due to their being influenced by European and American culture and art, and their turning their backs on Arab heritage. A number of writers from Shi‘ir moved to Hiwar, which was funded by the Congress for Cultural Freedom.

In addition to the prolific production of collective work and the commitment of literary figures to their political convictions and literary trends, as well as their uniting around publications such as Al-Adab, Shi‘ir, and Hiwar, numerous individuals moved freely and individually between contradictory spaces. In particular we were struck by the feminist writer Layla Balabakki, whose works were published in newspapers and who was the focus of heated discussions. Her novel A spaceship of tenderness to the moon was removed from markets in 1964, and she became the first Lebanese novelist to be tried for her writings. Balabakki was accused of violating morals because her novel included erotic references. Yet her struggle for new social values made her a friend to many intellectuals.

We were also struck by the life of poet Badr Shakir Al-Sayyab and his positions of support for pan-Arabism, making his a regular name in Al-Adab for years on end. Al-Sayyab also published his modern poetry in Shi‘ir magazine, and worked for Hiwar magazine, Franklin Book Programs, and the Congress for Cultural Freedom, which supported him even while exploiting his miserable life and his chronic illness.

Conclusion

Our research journey took us to Beirut, Damascus, and Berlin, where we visited numerous institutions and interviewed individuals working in publishing and history, as well as people who had been contemporary to the time and context of our research. This journey enabled us to build components of a catalogued archive that records information about over 50 parties, being individuals, regional and international institutions, groups, publications, and publishing houses whose stories we have shared with you. This research enabled us to follow the different ties connecting these parties, including relations of cooperation, work, funding, friendship, and love.

This work did not stop at reading and collecting materials for this archive, however, but rather raised questions about the writing of Arab cultural history and the extent to which archives can enrich us with facts that widen our perspective on the past, moving us away from sanctifying it and falling into the trap of romanticization. It was important for us to understand the extent of the complex relations between ideology and political conviction, funding, and intellectuals, as well as to what extent politics was adhered to cultural practice and made a factor in the birth and death of projects. The Cold War was a very specific cultural era that yielded to the conditions of the globalization we are now living. This assumption moves us to follow the common denominators between the past and present, and shed light on similarities and differences on the levels of finance, politics, cultural practice, and collective work. The 1960s experienced a shift of the nature of funding from strategies of translating Western works into Arabic, and propagating of Western knowledge in the Arab world, towards the integration of Arab intellectuals as partners in a global network of cultural players. In this way, local initiatives and intellectuals were supported and their voices were globally presented. Therefore, this investigation is researching the forms of cultural policy applied by bipolar powers had changed in relation to the support of intellectuals and publishing in the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. These policies were claiming through conferences, events, and project a sort of equality between the Arab intellectuals and their western colleges. In the wake of this new form of political approach, we are aiming to understand, how could Arab intellectuals find their own spaces of creativity, collectivity, and resistance within this new form of cultural globalization?