Territories of the Soul

Gaëlle Choisne’s diasporic vernaculars, counterfeited anti-canons, and scintillating luvs

The refusal of mastery

“Punk gestures, awkward because I never aimed to be a virtuoso artist of the classical era. Trembling of the voice and the hands. Doing it. Doing it. Uttering, stammering. Uttering, stammering, repeating it, like a loop. Recycling thoughts. Doing it wrong, worse, better. ‘Always do your best’. And then; inevitable disaster, or sabotage, oozing.1”

The verb “to master” refers to an accomplished knowledge, a perfected skill, and a constant know-how acquired through lengthy studies, often confirmed by institutional certificates and social recognition. It announces that things are under control: they are mastered; there won’t be any unforeseeable outcomes or formal shortcomings. European art history constitutes a long genealogy of “masterpieces” whose artistic achievements are attributed to technical skillfulness, patient maturation, and the signature of the head of the workshop, providing a guarantee of originality and authenticity2. Mastery provides the foundations of a refined cultural history, canonized and handed down through vertical transmission, from father to son, over generations.

Gaëlle Choisne labors at the opposite of this tradition. In a space of referential impurity, she is associating scattered recycled matter, pixilated images, fluid, unstable installations, multiple collaborations, and the permanent possibility of dysfunction. Serendipity, the finding of happiness, is ubiquitous in her work. Lack of control and amateurism are deliberate here and underlie a working process that rejects the authority of consecrated art history, names its gendered and racist bias, and claims its part through shaky gestures, and compelling heterogeneous cultural traditions and materials.

Choisne borrows from sources as disparate as the French semiotician Roland Barthes; spiritual healing practices accessed on Facebook; Hessie (1936-2017), a feminist Cuban artist living in Paris for most of her life, whose practice has been poorly recognized by art history; commercial pop cultures; and independent art house cinema. The components of her hybrid assemblages are drawn together along the lines of a diasporic imaginary: a fragmented articulation of a layered present in which here and there, bourgeois and popular, rational and intuitive, are dynamic coexistences rather than separated and opposed realms. She mocks mastery and authenticity as illusionary and exclusive and assembles instead what the writer and researcher, Nadia Ellis, calls Territories of the Soul:

“Spaces that embody the classic diasporic dialectic of being at once imagined and material, […] most lively as horizons of possibility, a call from afar that one keeps trying and trying to answer.3”

Gaëlle Choisne pursues a deliberately anti-canonical approach. She adopts traditions to which she has often not been invited; she copies, pirates, and distorts them, substitutes institutional exclusivity with rough, handcrafted counterfeits, and luxury with fake and pop4. She lurks lustfully into the well-hidden violence of seemingly noble classical traditions. The Silent Life of the Left-overs of a Bouquet of Oysters, 2018, for instance, a compilation of sculpted oyster shells made of plaster, ceramic, wax, pigments, salt, and silicon, and scaled up to 110 × 50 centimeters each, references not only one of the world-wide celebrated gastronomic specialities of the famous French haute-cuisine, mentioned in European texts as early as Homer’s Iliad. It refers to the oysters’ queerness, highlighting that they are hermaphrodites and change sex throughout their lives. It also recalls the common origin of the words oyster and ostracism: in ancient Greece, oyster shells were used for voting on the ban of undesired persons from the polis5. Choisne’s gesture complicates the history of a seemingly local maritime product and connects it to today’s hostile anti-migration policies and their historical antecedents.

In Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s dialectic of recognition, which develops a universalist theory of emancipation, mastery is depicted as historically limited and contested by the subjected on whom it relies. The master depends on its opposite, the slave, the subaltern. For Hegel, movement in history is induced by the contestation of the master’s power through the enslaved. While both figures depend on each other, the enslaved is the decisive agent of change. In her seminal essay Hegel and Haiti, Susan Buck-Morss has demonstrated that the German philosopher has drawn his seemingly abstract thought on the background of the Haitian revolution, which abolished slavery and established the first Black republic in the world in 18046. She shows that narratives of Universal history, widely shared by Enlightenment thinkers, gained recognition at the same time that chattel slavery expanded in the Caribbean and the Americas. Her essay stresses that this contradiction lies at the center of Europe’s global ascendancy and the rise of capitalism.

While the Haitian revolution claimed and adapted the egalitarian principles of the Republic beyond its application in the colonial metropolis, it did not overthrow the extractivist plantation economy that fed modern capitalism and still maintains the country suffering from the consequences of this asymmetrical inclusion7.

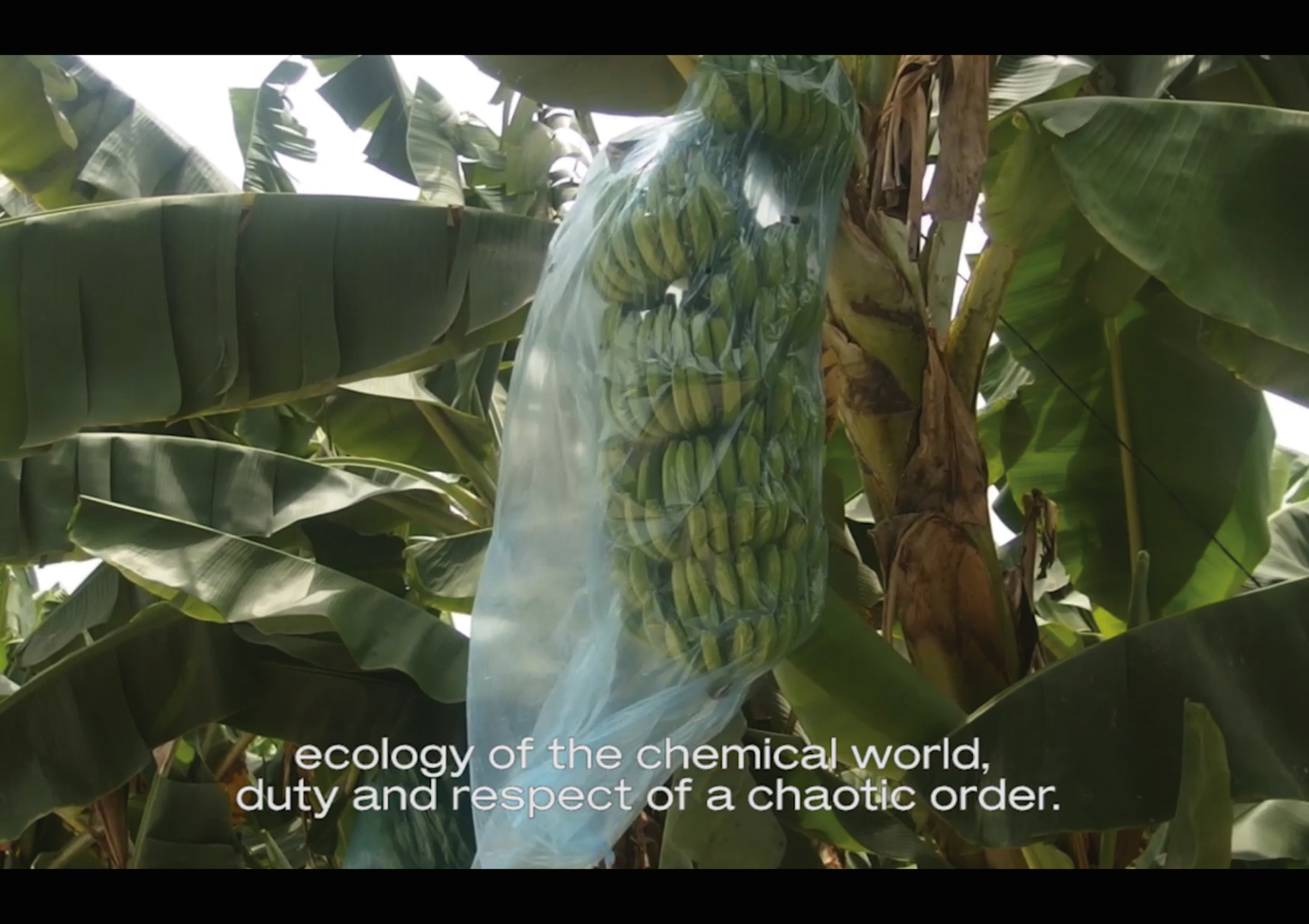

These briefly outlined historical entanglements resonate in Gaëlle Choisne’s film To Be Engulfed (2019, digital video, 25,36’). She edits low-resolution mobile phone images sourced from social media, which show the repression of demonstrations in the Haitian capital Port-au-Prince in July 2018, reacting to the government’s announcement to considerably raise fuel prices to meet conditions set by the International Monetary Fund, in a context of widely spread economic difficulties. She knits these images together with her own footage, interweaving shots of her body parts with erring images of ruins covered with vegetation, hand-held camera movements on the construction sites of luxurious private houses, a memorial for murdered Haitian-Polish communists, and footage from internet shows.

The narrative is built on historical entanglements reaching back to the 18th century: In the small city of Cazale, 45 kilometers from the capital, a community of Haitians with Polish origins still lives. They were brought to the country by Napoleon to help repress the anti-colonial uprisings but identified with the revolting enslaved people, deserted from the military, and joined the revolutionary forces8. Subsequently, when the republic was declared in 1804, they were accorded Haitian citizenship and settled lastingly on the island. In the 1960s, Cazale became a center for communist intellectuals who were opposed to the governing regime and its strong US-American affiliations. Eager to end the contestation of François Duvalier’s power, the paramilitary militia Tontons Macoutes encircled the city on March 29, 1969 and murdered and raped dozens to hundreds of people in the biggest single massacre of the Duvalier era.

Choisne is interested in the complexities of history and includes footage showing the solemn speech of Duvalier’s son and successor, Jean-Claude Duvalier, at the occasion of Pope John Paul II’s visit in 1982 (a man of Polish origin), in the presence of several officially selected representatives of the Haitian-Polish community. The artist films the ruins of an abandoned property of the ruling family while reading parts of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ Communist Manifesto from 1848, a text built on Hegel’s master-slave dialectic. While Hegel drew on the Haitian revolution without explicitly referring to it, thus presenting a major collective movement as an abstract idea, and Marx turns Hegelianism “from its head on its feet”9, Choisne takes the constitutive text of the successive Communist Internationals to present-day Haiti, spinning it one more time, and highlighting that class domination, extractivism, and exploitation do not belong to the past10.

The existential despair expressed in Roland Barthes’ chapter “To be Engulfed” in his A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments (1977), from which the title of the video is drawn, is recontextualised here by the images of monuments to murdered communists, syncretic worship practices, and new construction sites of the local bourgeoisie, interspersed with Choisne’s voice-over reading excerpts of Stuart Hall’s essay on multiculturalism11, the Communist Manifesto, as well as her own poems. It transposes the text from the individual confrontation with death as an abstract possibility to the engulfment as a socio-political condition: images of piles of false dollar notes; barehanded artisanal mining; television in Haitian Creole on the background of a photo wallpaper of a golden sunset; the Haitian shores filmed from a boat, and shots of clouds captured through a plane window, alluding to a diasporic access to social realities in Haiti; documentary footage of a Christian service broadcasted by a Polish website; and a man explaining Haitian history while his T-shirt reads “España.” These images are small hints to the complexities and depths of transnational entanglement, far exceeding the emotional experience in the private sphere.

Diasporic remixing and the contamination of the colonial archive

“Then came the white sisters clapping

to the waves’ progress,

and that was Emancipation—jubilation, O jubilation—

vanishing swiftly

as the sea’s lace dries in the sun,but that was not History,

that was only faith,

and then each rock broke into its own nation12”

In most of her work, Gaëlle Choisne refers less to Haiti as a signifier of emancipation than as a dense imbroglio of permanently hybridizing practices that she evokes in constantly recomposed diasporic mythologies. The excessive and disordered environments that she creates are charged with the persistent remnants of European domination and the disruptive occurrences of global capitalism. They carry the marks of colonial classifications that the distorted figures of her complex assemblages allude to while destabilizing and counterbalancing them.

In A Decolonial Ecology, the political theorist Malcom Ferdinand refers to what he calls the “hypothesis of Ayiti” (the taïno name of Haiti) as the simultaneity of coloniality and resistance:

“The hypothesis of Ayiti conceives the Earth as the pedestal of a world whose physical-chemical systems, geological strata, oceans, ecosystems and atmosphere, are intrinsically imbricated with the colonial, racial, and misogynist domination of humans and non-humans, just as with the struggles against them.13”

By choice of materials and through her working process, Gaëlle Choisne articulates this tension between domination and its contestation, and insists on her agency: while every work brings together a messy mix of matter—metals, fabrics, resins, clay, rubber, plaster, grids, chains, cheap consumer goods, and many more—all these heterogeneous components bear the traces of their manipulation. Choisne recurs to manifold crafts, often without previously knowing them, and keeps —even in the finished states of her works—the production process apparent. Subsequently, she reassembles the works dynamically for every new installation. The often allusive and narrative titles read as confusingly complex as the material components. Rather than relating to the work by describing or defining it, they add yet another possible entanglement.

One can think here of the sculpture provocatively entitled, Do You Like My Black Ass? (Resin, plastic bags, metal, wax, chains, 2018), an irregular, rough life-sized torso made of black resin, with golden chains and small flabby plastic bags pinned on it, resembling the breasts of an elderly, not necessarily human, female being. The whole sculpture is standing on a pedestal built of construction grids, bumpily welded into a squared shape.

Here again, the references are multiple: the polysemical ensemble speaks back to the tradition of idealized classical sculptures, the glowing whiteness of their “noble simplicity and calm grandeur14” and their normative proportions, and opposes to it a proudly monstrous torso15. Choisne presents the work as the re-interpretation of the Artemis of Ephesus, an alabaster sculpture from the second century conserved in Naples, which itself refers to the worshiped sculpted ebony figure at the Artemis temple in ancient Greece.

But the work evidently also references Sarah Baartman (1788-1815), the Khoïsan woman exhibited at public viewings in London and Paris, measured and dissected after her death, cast in plaster, and kept at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris for more than a century before ultimately being repatriated to South Africa for burial in 2002.

It also evokes the interlinkages between the Black Madonna of Częstochowa, an iconic 14-century painting of the Virgin Mary with the child, and one of the most worshiped images of Polish catholicism, to Erzulí Danto, the main loa (senior spirit) of the Petro family in Haitian Vodou. It is likely that the Polish soldiers who joined the Haitian revolution at the end of the 18th century brought reproductions of the painting and that these merged in syncretic celebrations with Yoruba gods, oluwa, that traveled with the enslaved Africans to the Caribbean. Erzulí Danto is the iwa of vengeance and rage, central to the Haitian revolution that started, as is told, at her annual birthday celebration. She is worshiped with cacao, golden jewelry, and an annual pig offering, and she is a prominent reference for single mothers in Haiti. Today, the Polish LGBTQ movement also uses the painting and represents the halos in rainbow colors. In 2019, the queer activist Elżbieta Podleśna was arrested and accused of profaning the image, causing major international protests, including by the US-episcopal church that started selling T-shirts with a print of the rainbow Madonna in solidarity. All these dimensions resonate in the sculpture.

As with many of Gaëlle Choisne’s works, the piece is frequently shown in changing configurations, shifting its meaning by renewed contexts. While Do You Like My Black Ass? strongly evokes the figure of the worshiped saint in the frame of the exhibition TEMPLE OF LOVE (Bétonsalon, 2018), it calls the history of racist oppression to mind, as well as the invisibilization of Black women, and queer resistance strategies when associated with the film The Sea Says Nothing (2017, video, color, 17 min) and the multi-media installation Backroom, or Please Let Me Know How We Could Vanish Before the Night, After the Rain (2017-2019; 4.5 m × 2.30 m × 10.50 m; ceramic fountains, resins, cigarette butts, coins, hot water, ephemeral tattoos, greenhouse structure, pumps that feed hot water to thermo-painted panels, paint used for cars).

The latter consists of an industrial greenhouse made of transparent tarpaulin and an aluminum structure that creates a humid interior space lit by neon lighting. The humidity is caused by a series of five sculptural, body-height installations, all composed of images of plants, exotic in European contexts. They are printed in zoomed-in fragments on aluminum boards, held upright by welded metal structures painted in pastel green, and standing in roughly crafted, enameled porcelain recipients sprinkled with cigarette butts and money coins. The parts are fixed with resins or latex, and electric motors pump to heat water through tubes that run over the images, as if they were constantly watered: a flow with a tranquilizing sound, reacting to the boards and bringing the tropical flower images to glow. Visitors are emersed in the installation, and experience an environment with all their senses simultaneously that evokes the European domestication of plants from colonized territories, here only present as stumbling, DIY-crafted, displaceable assemblages, and a potential space for transgression, as indicated by the title: the backroom, accompanied by invitation to vanish in moist and poorly lit off-lands at sunset, after the rain. The title stands in strong contrast with the brightly lit space of an exhibition heavily burdened with colonial vestiges, in which the visitor navigates between encrypted floral structures and discretely suggested queer counter-cultures.

anti-rust paint, coins, butts, pomp, thermic paint.Temple of Love–Absence, Musée d’art contemporain de Lyon, 15e Biennale, Là où les eaux se mêlent, © Blaise Adilon © ADAGP

In the midst of the scarce mask-wearing audiences of the summer of 2020, Gaëlle Choisne showed the installation in a weekly evolving configuration at La Grande Halle, La Villette, Paris16, together with the film The Sea Says Nothing. The title dialogues as a counterpoint with Saint Lucien poet Derek Walcott’s poem The Sea is History, a text recounting the genesis from an anchorage in the Caribbean and accounting for the destructions caused by slavery and the plantation. It is a quote by Carmen Brouard (1909-2005), a Haitian pianist, composer, and distant relative of Choisne’s family, whose homonymous composition underlies the film. Footage stretching from black-and-white silent films to George Romero’s famous zombie movie Dawn of the Dead from 1978 to contemporary internet clips uploaded by anonymous private users are edited together, partly inserted in a looping shot of waves on the high sea. The film navigates representations of Blackness in cinema, inquiring about the unexpected fault lines in racist imagery, systematically counterbalancing the latter, and unsettling its authority.

The first sequence of black-facing in Jean Renoir’s Sur un air de Charleston (1926, black and white, 25 min) is prolonged by internet footage of two white girls, filming themselves while applying charcoal masks on their faces. Choisne frames their publicly displayed intimate action by a visual superposition of the low-tech rendering of a smartphone, insisting on the inversion of the sense of observation as if she was telling them: ‘I am watching you!’; before applying a whitish nutritive cream with added green paint to her own hands. Through her editing and the special effects, savagery changes sides and points to continuities of denigrating cultural representations or resorting to mockery and inversions: in Renoir’s film, an African man travels to Paris in an imaginary future a hundred years ahead (that is, back then, 2028) - finds the city devastated, and meets a young female dancer teaching him primitive white dances, directly derived from the cabaret stages of the 1920s.

Inversions and the exoticization of European cultural patterns are the structuring principle of the film, which jumps playfully from the Afro-futurist Space is the Place (1974, 85 min), authored by the experimental artist and Jazz-musician Sun-Ra, to examples of inverted cannibalistic panic, as recorded by the British anthropologist William Winwood Reade in his travel account Savage Africa, published in 1864 after his journey across Angola. Reade narrates the fear of a young African woman whom he had tried to kiss and who was afraid of him attempting to eat her. While the text presents the scene as a cultural misunderstanding, highlighting the surprise of a European man to be considered as the cannibalistic savage, one can read between the lines the likely use of gendered violence perpetrated by the author on the woman.

The film further includes an action scene from Romero’s successful zombie film Dawn of the Dead, featuring the heroes, three armed white guys, trying to run away from a crowd of zombies pursuing them in a shopping mall. One of the scenes used by Choisne shows them behind the closed glass doors of the mall, poking fun at the zombies outside. It leaves the representatives of the American white middle class in their seemingly safe existence, locked up in the fortified shopping center, while the world around them succumbs to chaos. Choisne’s editing points thus to the self-confident consumer cultures, enjoying their existence as long as they can shield themselves from the excluded. And it underlines the weight of the representations of zombies in US-American cinema that largely dominates the representation of indigenous practices today17. These are celebrated in her film Accumulation primitive (2020, in progress), in which Choisne engages with present-day practices of plant potions and spells. She films Madame Café, also named “Docteure Feuille” (Leaf Doctor), an initiated healer and midwife, in her preparation of remedies, philters and mixtures of plants, with a variety of purposes, potentially including zombification. Gaëlle Choisne’s use of the scene from Romero’s movie with a nearly all-white casting in which the memory of slavery has disappeared operates as a counter-point to these practices and comments on their intentional oblivion in the voice-over. Romero’s film resurrects zombification in the context of capitalist consumption, as the return of the living dead provoked by the brutal devaluation of labor through economic forces that remain occult18. By bringing the film together with representations of Blackness in cinema, both racist and emancipatory, Choisne insists on inscribing slavery and the plantation in the history of capitalism while also pointing to its omission in the transformation of the zombie as a broadly shared signifier in global cultures. Excerpts from afro-futuristic narratives like Sun-Ra’s Space is the Place appear as vanishing points to escape from the repetition of domination. The film ends with Choisne’s voice, pronouncing a poem on love and remembrance as a potentiality, as the camera flickers over parts of two standing bodies that never appear fully, repeatedly focusing on two interlaced arms, a black and a white one.

Trans-spatial incarnations

Choisne’s images and installations take the viewer to and fro the colonial archive, from her native French city Cherbourg to urban Haiti, from the capital of the Netherlands to export economies in China, from a long-term residency at l’École des Actes, a plurilingual cultural project in Aubervilliers, to a cosmopolitan working-class suburb in the North of Paris, to luxurious private spaces of metropolitan art collectors. Her gestures keep crossing and blurring division lines between supposedly separated cultural traditions, messing up illusions of purity, slyly contaminating bourgeois traditions, and investing in and subverting exoticist desires.

A striking example is Patte de Pintade (oiseau nègre), 2017 (ceramic, necklace chain, lead), a cast of a guinea fowl’s foot. Guinea fowls have a complex and changing cultural history in the Haitian context, as they represent the resistance to enslavement, but have also been integrated into the National flag by Duvalier. The bird has been described as marooning, as it escaped from domestic culture and regained life in liberty. Guinea foal’s feet are considered a talisman for protection against evils and spells, and their presence in Haitian dishes recalls and commemorates the history of maroons as an alternative source to written history19. Choisne presents them in the shape of a small sculpture suspended on a golden chain and a stick hanging from the wall. On first appearance, she displays a supposedly ‘authentic’ element of Haitian culture and hands it over to the avid gazes of the art audiences - only to secretly subvert it: the talisman is made of lead, and though the toxic properties of this heavy metal are invisible, they discreetly poison the lucky charm. Hence, the “postcolonial melancholia20” here expressed in the European desire to control cultural practices of formerly colonized territories through their fetishization is unsettled through the silent agency of matter. Choisne further counters the objectification of the original through its multiplication, commodified forms of consumption, and shared cultural practices. During her exhibition Hybris at the galerie Untilthen in May 2018, she invited the artist Jephthe Carmil to prepare and share a “pintade marronne.” Carmil inscribes his gesture with the commemoration of resistance through culinary practices rather than through official accounts of history. Choisne further included repeatedly in her exhibitions chicken feet produced in China, sealed in PE, and shipped worldwide: a cheap commodity, a product of torturous meat batteries, reducing the birds to tradable objects, and feeding them into global commercial structures, as a product sold online, becoming an instant ingredient for culinary or ritualistic use across the world.

In her sculptures, films, and installations, Gaëlle Choisne accounts for the distorting impact of racism while unsettling its authority and shifting the points of reference. Some of her works challenge the colonial archive by directly addressing it, as she does in War of Images! Distortions and temporal ellipses (2017, 100 × 100 cm; 250 × 126 cm), a series of twelve printed offset plates arched between two ceramic sticks that fix them asymmetrically on the wall. With a perverse ambiguity, the plates show, on their seductive shiny surfaces, scans from anthropometric drawings that Choisne has found in the archive of the Rijksakademie, Amsterdam, where she was a resident from 2017 to 2019. With the help of machines and superposing several layers of images, parts of her body (her hands, fingers, and face) are included in the scan and plotted on top of the drawings in the final UV print on the plate. Choisne inscribes her own body in a genealogy of nameless subjects who have been reduced to evolutionary types by racist science. The image renders her body parts simultaneously glooming and distorted, magnified and injured, strongly affected by the history of dispossession and exoticization perpetrated in the frame of European colonisation and its ongoing consequences in the present.

While bodies are mostly alluded to, rather than literally represented in her exhibitions, Choisne grounds her sculptural spaces in her embodied experience, extending her own skin through the artefacts she creates. Peau de chagrin (2017, silicon, photo paper, 2m2) is literally a skin, made of fine, superposed silicon layers, carrying images of a cave in the Dordogne region in the French countryside, and leaves from a corossol tree in Haïti, merging visually and materially both geographical references. The imaginary landscape becomes a skin: the porous border between the body and the world, the subject and the other, the organ for sensing contact, and simultaneously a racially highly signified, inescapable surface of projection. Choisne refers to the romantic trope of the landscape as an externalized mirror of the soul in 19th-century art and literature, inscribing it in the skin while dissociating the latter from the body. Once more, she borrows the title of her work from a canonic classic, generating multiple resonances with it while reframing its meaning. In Honoré de Balzac’s novel Peau de chagrin (1831), the protagonist obtains possession of a skin that allows him to achieve his desires. Belatedly, the hero becomes aware that the progressive retrocession of the hide shortens his own life. Choisne’s Peau de chagrin is not handed over to her but created by herself, a chosen space intimately related to her lived experience. The sculpture is physically suspended on thin golden chains that are both ornamental and coercive: It brings a diasporic imagination into material existence and creates an elective territory torn between burden and jubilation.

Celebrating Luvs – Politics of Kinship

“I tremble.

I tremble at the thought of seeing him again after 200 years.

I tremble because he has surely changed.

Maybe he won’t recognize me again, or make me blush.

I melt.

I tremble so much that I cannot control my shaky legs anymore.

A fear mixed with excitement engulfs me.

I recognize you21.”

Gaëlle Choisne’s territories of the soul strive to open up spaces for reciprocal attention and affection. Amidst a burgeoning multiplicity of disparate material bodies, equally crafted and traded, she elaborates gestures of care and connection. Her work provides the settings for reconfiguring relations and accompanies the physical installations in the space with symbolic relations to absent or omitted historical figures. She calls them her luvs, picking up the voluntary misspelling of “love” by contemporary urban youth, which also shifts the word’s meaning. Luv is an expression of affection without being burdened with the magnitude of love22. Hence it participates in a web of intersecting partly chosen genealogies and affinities, activated by encounters, spiritual practices, exchanges, and caring gestures. Choisne’s post-romantic luvs are not understood as belonging to the private realm, but rather emerge in a dense web of kinship that she alludes to or welcomes into her exhibitions. They take place in the exhibitions and as a series of events dedicated to a practice or a figure.

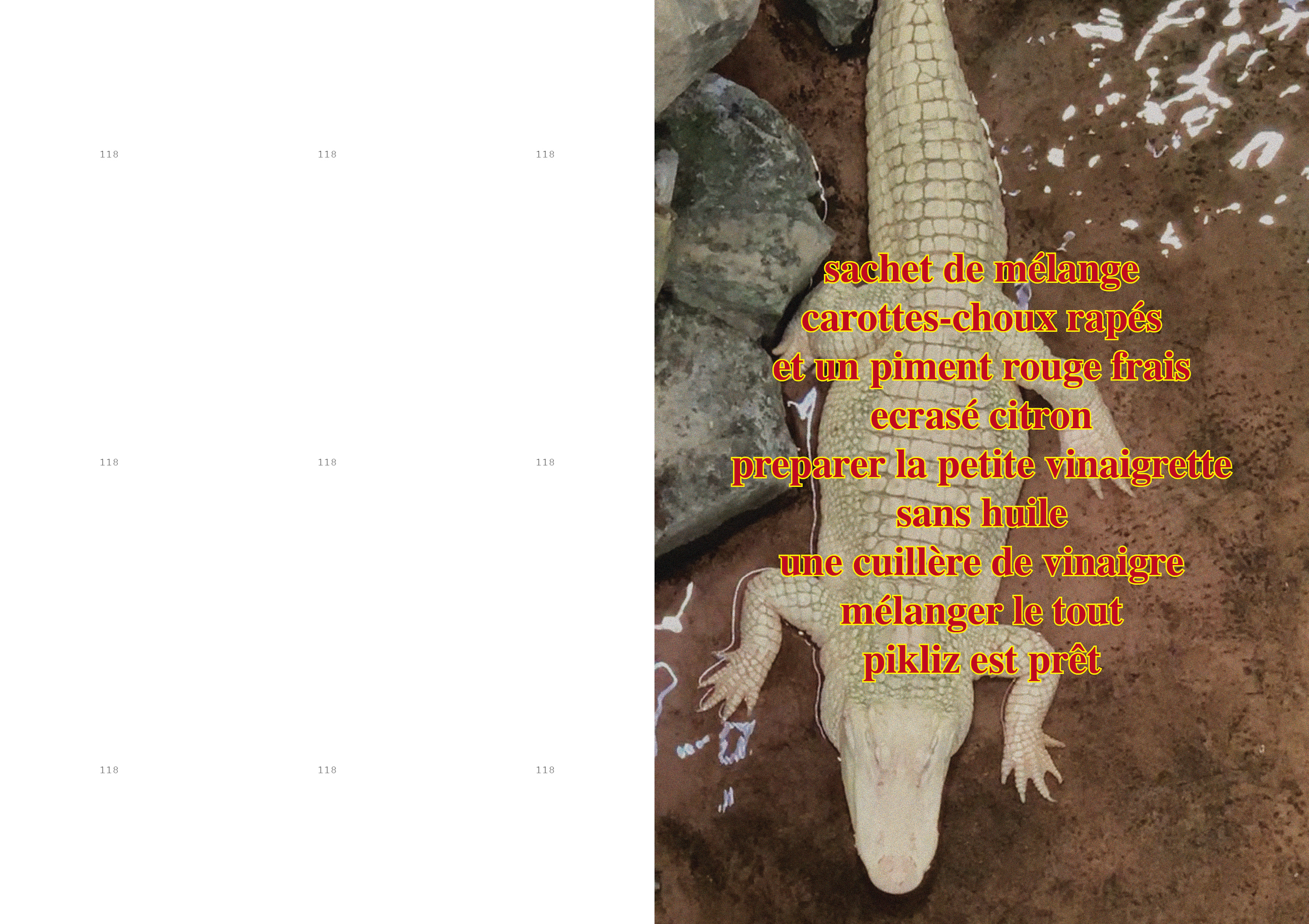

Choisne cherishes food as a cultural transmitter, insisting that her relation to Haiti first occurred through tastes, which is even more important in the context of French universalism that strongly discourages discrepant and minoritarian cultural practices.

Over the past years, she asked her mother to tell her recipes of Haitian dishes and integrated them in her exhibitions and publications, with the double attribute “Marie Carmel Brouard (my mother)”, bringing together official recognition of a publicly unknown woman, and her biographical connection to her. Though minimalist texts, the recipes refer to experiences of tastes, colors, and smells and visits to stores to shop for ingredients, which can be difficult to find sometimes. They also point to a narrative dimension, rendering her mother’s native country present as if it would still determine the changing compositions of the ingredients, as expressed in the lapidary last line of the “riz nat” recipe: “Add Salt Pepper Persil Thyme if available.” The sober form of the recipes does not diminish their powerful testimony of how cultures are made of improvisation, affect, personal transmission, and the permanent site-specific rearrangements of available components.

It would be mistaken to read these constant remixes as a harmonious global community living together in undisturbed unity. They emerge in disordered and difficult conditions and often bear the traces of these journeys. In her performances and workshops, Gaëlle Choisne has repeatedly proposed to prepare a Colombo, a tasteful dish named after the Spanish conqueror whose Atlantic crossing initiated the ferocious history of the Modern World, built on genocide and expropriation. Turning the ingestion upside down, she infuses the navigator’s name in the recipe through a mixture of spices that the imperial recomposition of the Caribbean populations have generated: curry powder brought from Sri Lanka by the indentured workers, who were displaced to the colonized islands to work on plantations since the 19th-century, mixed with locally available vegetables and plants to replace missing ingredients. History here is accessed through practice, culinary and popular culture rather than great narratives. The recipe becomes a script and guides moments of transmission and renegotiation. Choisne’s workshops offer participants the opportunity to get acquainted with local stores selling the spices, to compose and cook the dish together, to share its history, and to take it as a starting point to inquire about the close ties between (post-)imperial violence and cultural resistance. The meal is introduced as a ritual, marking a symbolic moment with a shared cultural signification agreed upon by the participants. It is a site of potential conflict arising from the recontextualization of the preparation. Choisne enables, for instance, the inverted cannibalistic ingestion to be vegetarian while insisting not to evacuate its symbolic strength, enquiring thus: what does it take for a sign to be operative, and when does it become too light to activate meaningful negotiations?

Politics of kinship are also navigated in Gaëlle Choisne’s installations as they open spaces of mutual attention, seduction, and joyful devotion. She understands them as post-romantic and composes these spaces of elective affinities out of crafted imitations of commercial symbols of love and affection: Love (2018), a plaster cast of two pastel-painted hands forming a heart; Ne me bannis pas de ton coeur (2018), a golden chain wrapped around a suspended oyster shell cast in white bronze, holding it as in bondage; A Hand to Take (2018), the rough cast of the hand of Choisne’s ex-partner, wearing fake nails and holding a pearl; lovelocks, a Vanity Ashtray (2019) with fancy colors and cigarette buds; but also the small sculpture Grandma’s Hands Explaining Me How the Sea will Kill Us (2020, ceramic and seashells).

Most of these campy objects point to their ephemeral character; they are part of cheap capitalist consumer cultures with low thresholds of accessibility. They can easily be shared, given away, and understood across the globe, with the notable exception of economically and culturally dominant classes, who would consider them of bad taste and refrain from using them. They are the expression of minor cosmopolitanisms23, abundantly practiced on the peripheries of global cities across the world. They can be quick inebriations, signs of seduction, such as the omnipresent cigarettes and cigarette buds in Choisne’s installations, the promise of easy ecstasy, and the rapid arrival of disgust. But they can also evoke offerings arranged on small altars, hidden or ostentatious places of devotion.

All these highly mobile cultural signifiers share an ability to create connections and condense memories across distant generations and geographies. While many of these objects are light and easily removable, they can mobilize affects, touch the body, and stick to the skin, as does, literally, the series of customized ephemeral tattoos that Choisne designs and orders online. In her exhibitions, she applies them on objects’ surfaces or prints them on pages, extending once again her own skin through objects and regressively recalling adolescent decoration practices.

In the space, Choisne relates to the bodies of the visitors, inviting them to make use of her works: To Sit on Chance, i.e., on printed cushions for relaxing; to perform or get a drink on the table sculpture Altar (2018); to get to the floor or stand on the tip-toes for better viewing a hidden detail; or to walk in the space to change the view axis. Her luvs are built practically through transmission and sharing and symbolically by paying tribute to ill-recognized historical figures. One of these is the aforementioned Haitian composer Carmen Brouard, whose compositions are included in several of Choisne’s installations and films. After learning about her work at the Centre International de Documentation et d’Information Haïtienne, Caribéenne et Afro-canadienne (CIDIHCA) in Montréal, and meeting her relatives and friends who take care of her compositions, Gaëlle Choisne aspired to stage the work as live concerts. Over the past years, she has repeatedly invited musicians to rehearse Sonate vodouesque (1977) during the opening hours of her exhibitions, accounting thus once again for transmission and embodiment as enduring practices and enactments.