Introduction by the editors

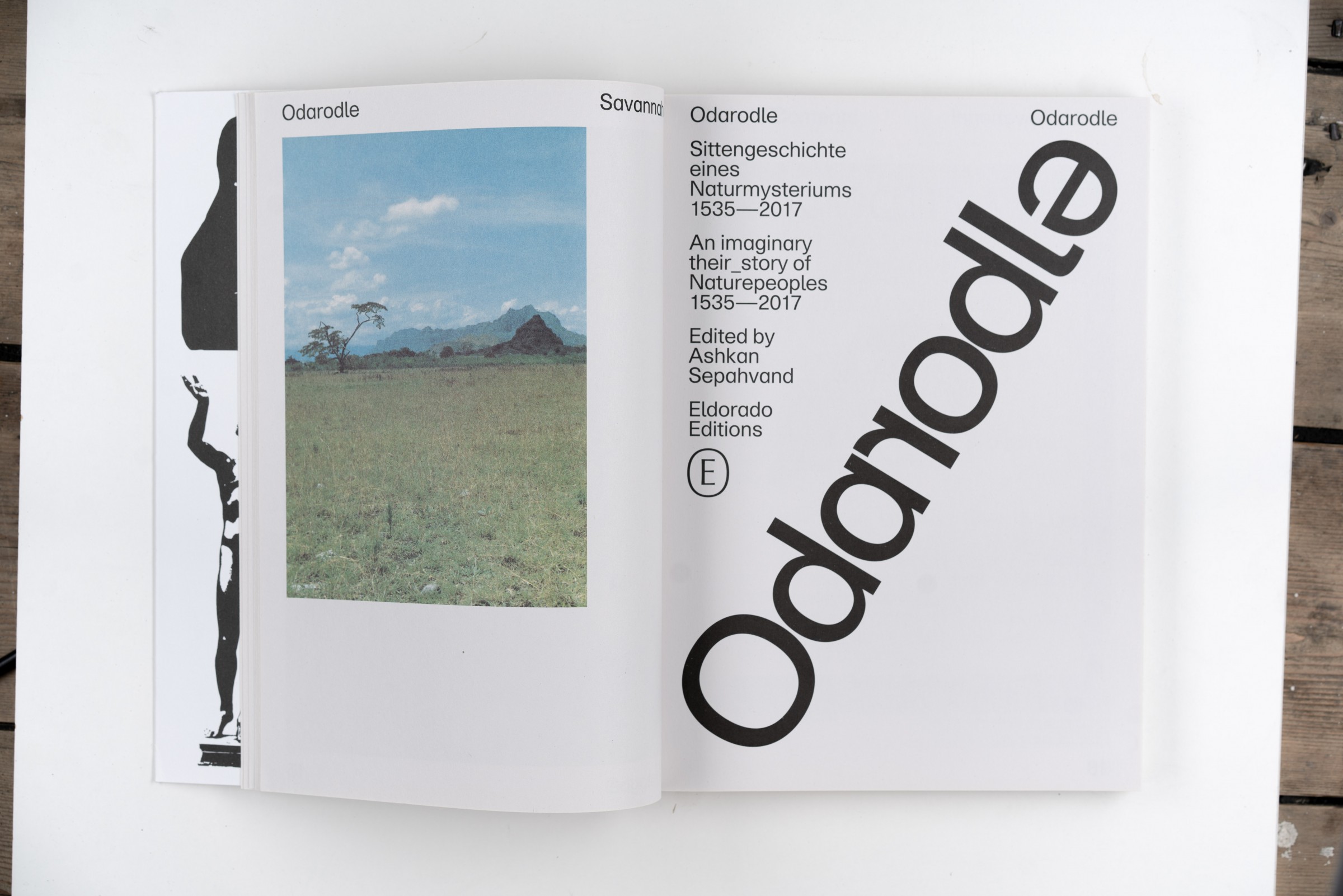

The original version of this text was written for the exhibition catalogue Odarodle: an imaginary their_story of naturepeoples, 1535-2017, conceived by the writer, translator and artist Ashkan Sepahvand. It was the outcome of a residency at the Schwules Museum in Berlin — the gay museum of Berlin was founded in 1985, following the exhibition Eldorado – History, Daily Life and Culture of Homosexual Men and Women in Berlin 1850-1950. This founding exhibition served as a starting point for Ashkan Sepahvand’s critical research, begining with the inversion of its title. The Odarodle exhibition, which took place from July 21 to October 19, 2017, presented contemporary positions that responded to the Museum, its archive, its history and its practices as both research material and aesthetic medium. According to Ashkan, “the project and its resulting publication rel[ied] on methods of artistic research and associative composition in order to sensualize and complicate seeing, showing, reading, thinking, and knowing.” Ashkan’s introduction to the catalogue and the exhibition reflected on his consent to embody an “other” position, when invited to revisit a dominant history of homosexuality — thus running the risk of cooptation. It also questioned the modalities of representation, vision and exhibition at stake in a European history of knowledge, by skilfully playing with the codes and vocabularies of such disciplines as ethnography and museology. Both threads of reflection strongly resonated with Qalqalah قلقلة’s preocupations around the effects produced by the circulation of artworks and stories through different contexts.

In our opinion, this text deserves to be widely read and discussed. That is why we invited Ashkan to offer it a second life on our platform after its initial release in the printed exhibition catalogue. We also undertook the challenge of collectively translating it into French. Although Ashkan’s text deals with a specific collection and history, it echoes important debates currently stirring the French artistic, intellectual and political fields — from the return of stolen artworks and artifacts to the role of museum collections in the production of dominant and/or alternative narratives1; or the tensions and resistances around such notions as intersectionnality, among others. Five members of Qalqalah قلقلة (Line Ajan, Virginie Bobin, Vir Andres Hera, Victorine Grataloup and Salma Mochtari) worked together with anthropologist and poet Mihena Maamouri over the course of one year, through bi-monthly meetings enriched by our respective positions and experiences. We also commissioned an Arabic translation by Ziad Chakaroun, which generated another investigation on the (re)invention of language and vocabularies (forthcoming).

Ashkan’s text offers a lucid self-reflection on methodology, rooted in a playful relation to language. It opens unexpected perspectives on the situated writing of their_story and requires combined imagination and erudition from its readers and translators. We are grateful to Ashkan for allowing us to reactivate this text and for generously accompanying the adventure of its translation. We also thank the Schwules Museum for granting us permission to republish the text.

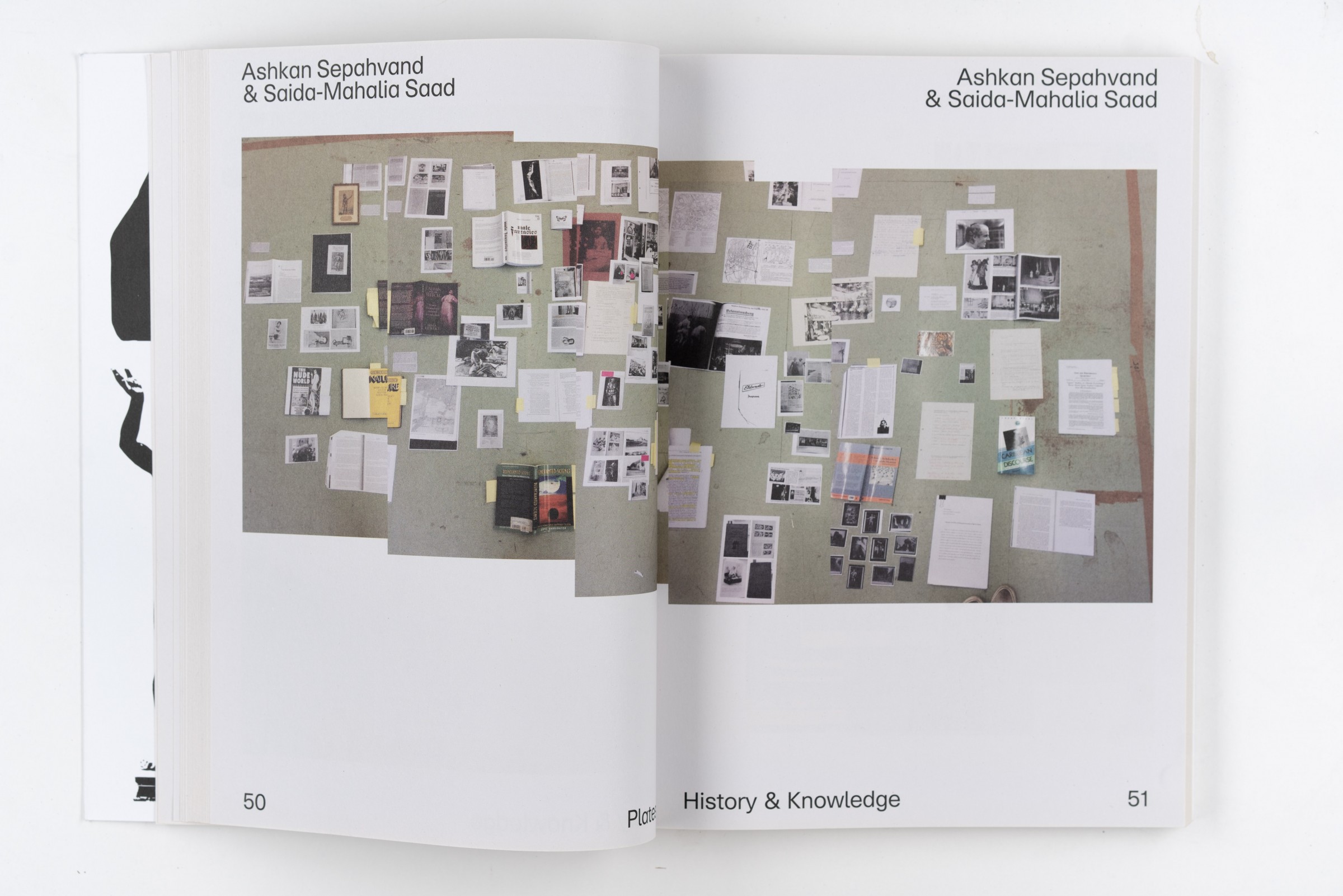

When I first started my research at the Schwules Museum in April 2016, the project I was to undertake was outlined in advance for me. It was called Another View: Postcolonial Perspectives in the Schwules Museum. Its parameters for critique and reflection strove towards creating a space where “other” positions outside of the canon of official homosexual history could finally speak and be seen [or, show themselves]. Here I was, an individual who in many ways seemed to embody this other position – a person of color, possessing a migration background, moving in between various communities and intersections of race, class, and gender. My work was, in this implied equivocation between one’s apparent identity and assumed practice, to represent this difference; to account for the absence of other(ed) histories beyond those of gay, white, German cis-men – the Museum’s founding demographic – and to offer another view.2

I began to question this framework of representation. In particular, the desire to show a type of people, another category of Other, an othered Other, to make their story visible, accounted for, and heard. Who are they, anyway? Who is addressed by a “postcolonial perspective” – that is, who and what are now to be included, but also, to whom are these inclusions presented, and with what intended effect? Would my project merely point out the obvious – to demonstrate the historically-contingent limitations of the Schwules Museum’s archives and collection – or would it instead offer a revisionist re-reading3 that reinserts other figures into a history that is already that of a greater category of difference, that sociopolitical fiction known as the homosexual?4 It became clear to me that neither approach would suffice: one seems performatively self-effacing, the other smacks of late liberal relativism.

Just as much as the question “can the subaltern speak?”5 has been answered with a cogent argumentation that no, indeed, she cannot, for she is always spoken for, one may just as well pose the question, “can the subaltern show herself?” – that is, can those Others, all those forms of life who have been systematically occluded by history, ever reveal themselves? Can they cross the threshold from margin to center, from invisible to visible? Or would they, despite one’s best intentions, remain imaginary – an Other composed of its images alone, a fantasy of inclusion, an illusion of transparency?6 An Other that does not, cannot show herself; she is, rather, merely shown. If an Other cannot show herself, but is always shown, then the question turns back in on itself, onto the viewer, the subject who sees. Who is doing the looking?

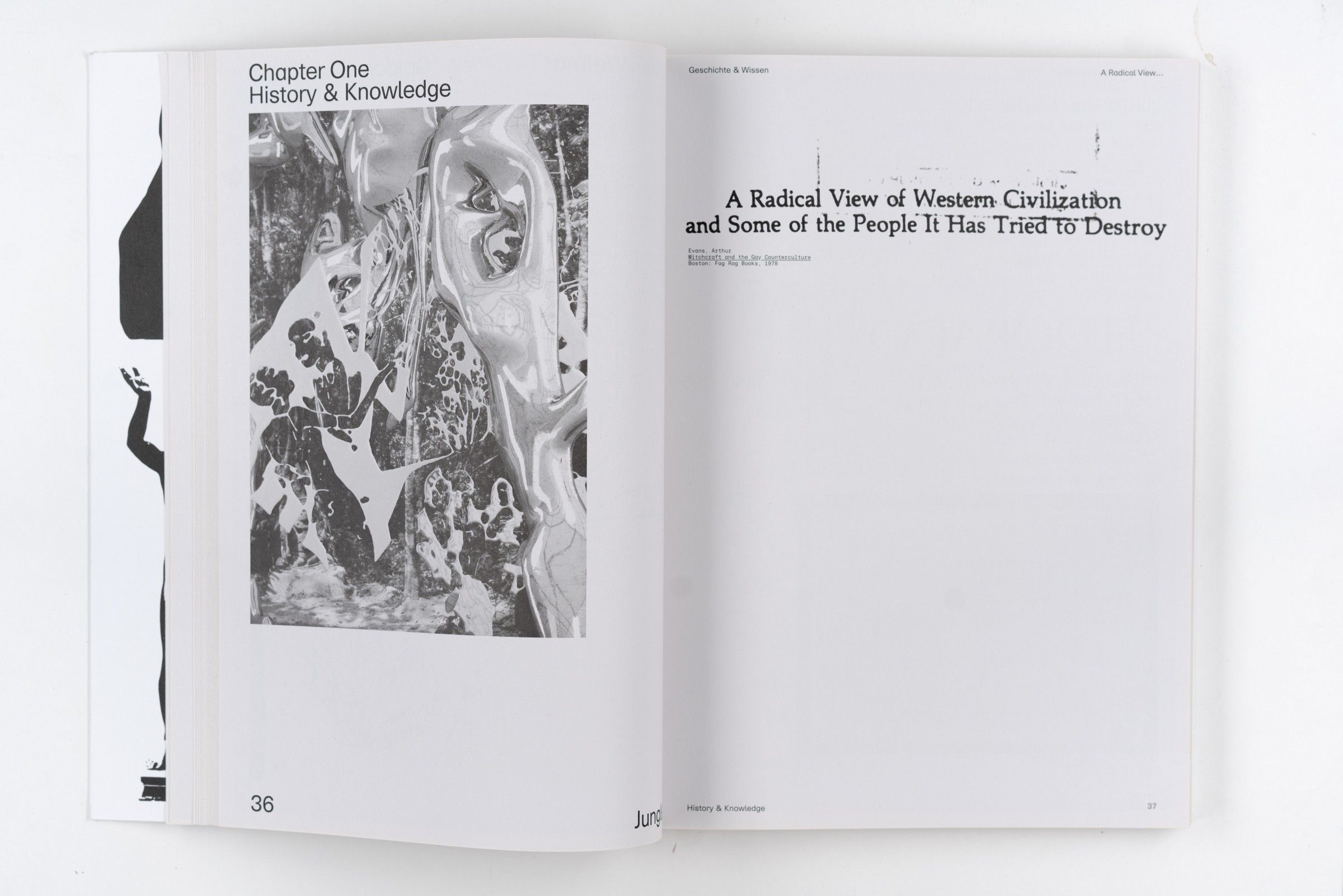

It felt necessary to go back to a more primary moment within the history of Western representation: to unpack the concept of perspective. Indeed, the development of pictorial perspective from the Renaissance onwards coincides with the rise of Europe as a colonial power. This is not a coincidence. The birth of this new “science of pictures” in the late 1400s occurs as part of a greater recalibration of social reality to the conditions necessary for early capitalism’s advances, further accelerated by the European encounter with and conquest of so-called new worlds from the 16th century on. During this time, one can trace a growing desire to capture the strange and exciting presence of unfamiliar forms, figures, and forces, to re-present them as objective, accurate, life-like pictures of what they are – the visible as true essence, the eye as objective viewer, the picture plane as geometric reality. At first, it may appear silly to suggest that a specific technical development in the history of image-making has any greater relevance beyond the formal constraints of art history. And yet, I would insist that the deployment of perspective, both informed by and informing the political, economic, and philosophical transformations in Europe and its relationship to a perceived outside, has been fundamental to the construction of the Other as a category of perception, and thus, representation.7 This imperial gaze, as one may call it, has striven to make of many worlds – of the incongruous multitudes – simply one world, the world, a universal view, imposed onto the globe. The eye within the perspectival tradition reveals the “I” of Power: an unmarked, anonymous, omniscient position, the Norm. For this eye/I to know itself, it must superimpose the mark of difference onto its surroundings in a centuries-long, interdisciplinary operation to capture and name the Other, make images of it, study it, display it, and finally, to define what it is, or rather, what the eye/I is not.8 Women, people of color, the poor, the mad, the vagrant, all those individuals and groups displaying non-reproductive sexual desire, and even Nature itself were to exist in this category of the negative. Their representations abide by the desire that the eye/I has to see not only what it wants to see, but what it needs to see for its ultimate purpose: domination over difference, self-confirmation through othering.9

To speak of other perspectives, then, is impossible, for there is only one perspective: Western, patriarchal, and capitalist, which has subsumed its blind spots, re-imagining that which is invisible according to its a priori conditions for visibility. The Other might and does appear, and constantly so; it is, however, only seen when its appearance is fitted, modified, or transformed for the sake of the dominant eye/I that is to see it. That is, its recognition is partial, conditional, and skewed – the Other is only acceptable within the visual field when she passes. The moment her difference disrupts the continuity of linear perspective, she is either removed from the picture, or held accountable for a crime that is, in the end, simply reducible to her inconvenient presence, her uncomfortable reminder. Following this argument, not only are images of the Other immediately problematic, cursed as they are by the initial motivations that created them, but the apparatus of vision is torn between its cultural programming to perform the criteria of objectivity while simultaneously believing itself to see naturally. To represent another view, or rather, “an Other’s view” is a trap – a trap many of those who feel the weight of their difference in relation to the eye/I are convinced is a necessary burden.10 If we were to take ownership over our own representation, so the reasoning goes, then history may be more just, they may finally understand us, for we are the ones who have put ourselves into vitrines. Rarely is it questioned to what extent the Other accommodates her own representation to the conditions of intelligibility laid down by the Norm. With this in mind, I realized that my project must aim to alter the conditions of viewing itself, to modify how one is able to see, to disappoint and disorient the eye/I, and in doing so, draw attention to all the ways in which vision is by no means natural.

Along these lines, the original project – to cast a postcolonial perspective onto LGBTIQ* histories – is an impossibility, for the colony has not ceased to exist. After the more historical forms of its territorial expansion and its material accumulation, the colony remains as an oppressive force within the mind itself, in how perspective constitutes the basis for modern knowledge. Thus, the task here is to decolonize the eye that sees and thinks within this perspectival framework, which means devising strategies for presenting forms to vision, apperception, and cognition that do not lend themselves to recognition. In this way, these forms retain their inherent queerness and are thus able to escape the dominant visual operation that desires to grasp their difference so as to annul their capacity to make a difference – the same operation that offers ‘another view’ as an opportunity for full exposure, whereby the Other willingly gives herself over to misrepresentation.

To resist capture is no easy task. It requires developing methods for showing without revealing, for resisting expectations of clarity and comprehension by instead emphasizing abstraction, complexity, and contradiction. It requires creating conditions for deceleration; the long-term processes through which the Other has been pieced together as a scattered sum of exclusions cannot be repaired in one go, nor can our eyes aesthetically unlearn well-trained patterns of understanding on command. To slow down, to spend time, to come to terms with not being able to, nor even needing to understand, to forego grand universals for small-scale particulars – these are the basic requirements with which we may begin to decolonize perspective.11

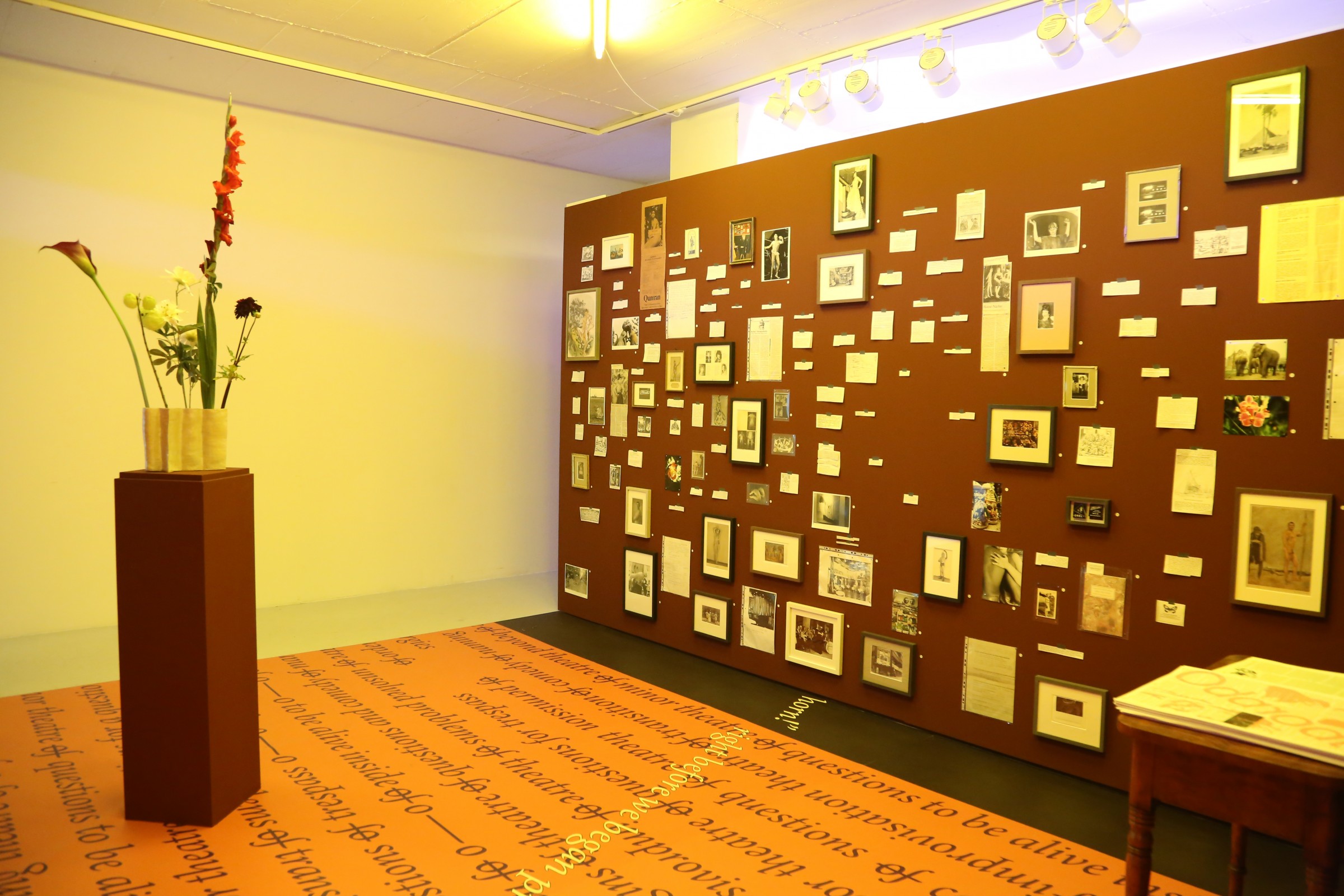

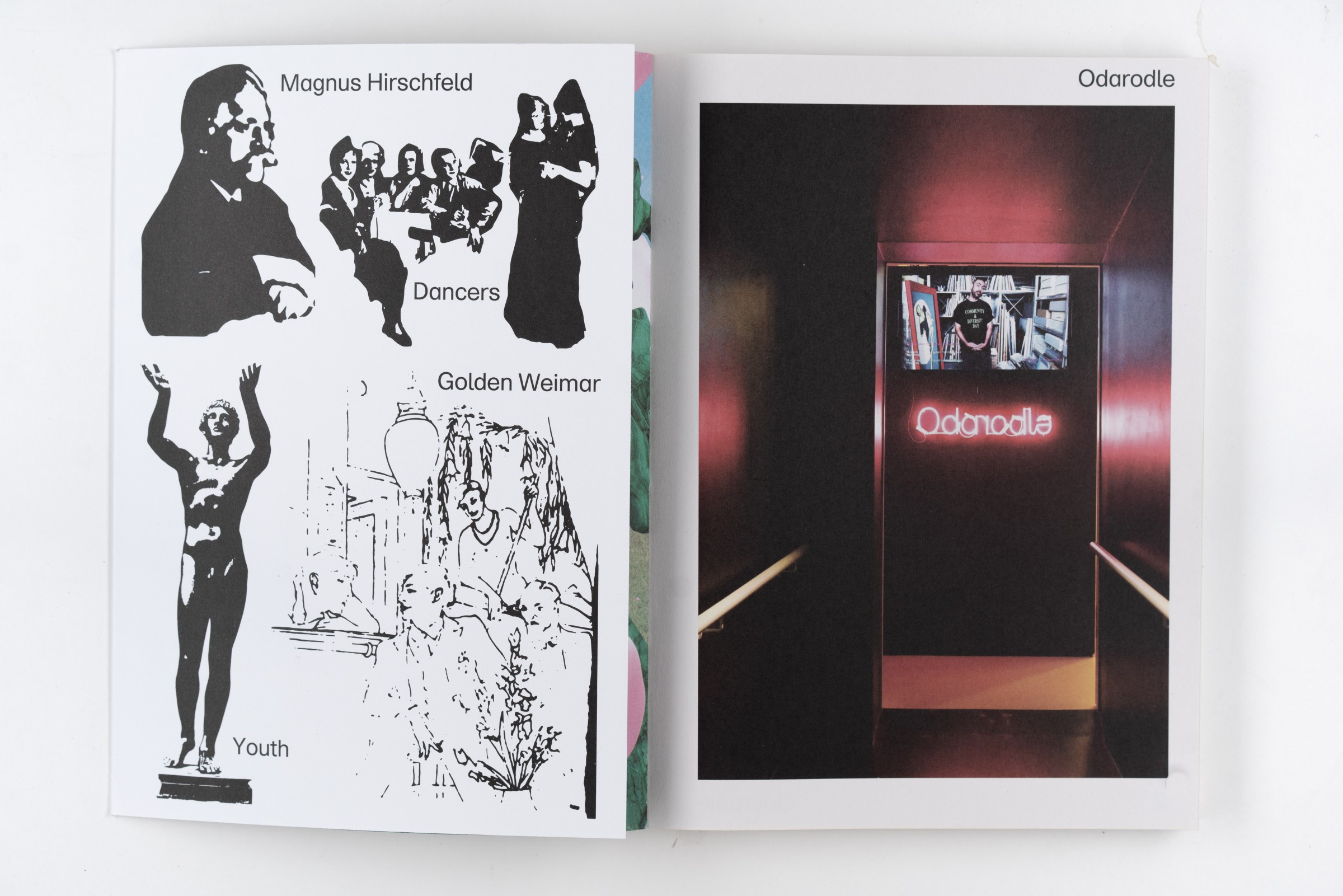

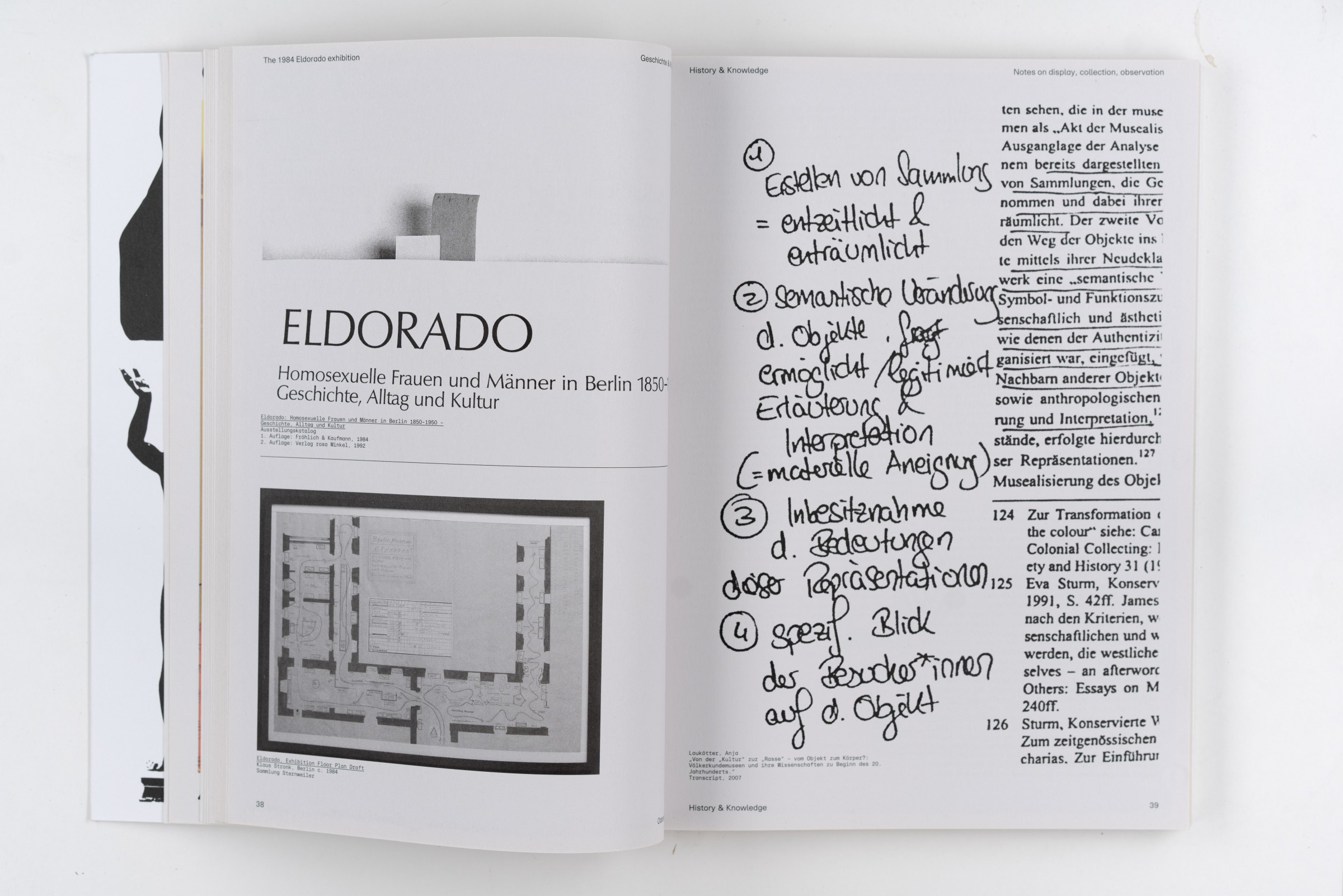

What happens when the Other takes up the opportunity to show herself? This is a question I directed to the Schwules Museum*, in particular the historical conditions for its founding in 1985. A year earlier in 1984, a working group of activist and academic lesbian women and gay men curated the exhibition Eldorado – Homosexuelle Frauen und Männer in Berlin 1850-1950, Geschichte, Alltag, und Kultur, which was shown at the Berlin Museum, West-Berlin’s municipal history museum.12 As much of a success as it was a scandal, the exhibition presented for the first time in a major German public institution a historically comprehensive consideration of homosexuality – from its origins in 1864 as a medical term for sexual inversion to its criminalization in the German Penal Code under Paragraph 175, effective in the Federal Republic until 1971 – as well as the significant contributions of homosexuals to the greater cultural and intellectual vibrancy of Berlin and beyond – from Magnus Hirschfeld’s influential work with both the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee and the Institute for Sexual Sciences to the widespread dissemination of journals, magazines, and newspapers written by and for homosexual women and men championing sexual freedom and moral reform. The title of this exhibition referred to the legendary Eldorado cabaret, a nightclub venue infamous for its “transvestite” performers and its diverse clientele of artists, expats, and social outcasts mingling with celebrities and politicians. Eldorado operated two locations in Berlin-Schöneberg from 1926 until its closure by the National Socialists in 1933, with one of the original locations re-opening after the Second World War. The Golden Twenties of Weimar-era Berlin served as the main focus for the exhibition’s materials and narrative. No wonder – these years are time and again invoked to fortify the myth of Berlin as a city of unparalleled debauchery, experimentation, and personal freedom, a kind of original habitat or a Paradise Lost for an imaginary “indigenous” population of freaks, failures, the rebellious, and the itinerant who to this very day are still drawn to the city as home, would-be natives eager to perform autochthonous imaginaries. Seen within the greater canon of homosexual history as composed by the Gay Liberation movements of the ’60s and the ’70s, the Eldorado exhibition provided a pre-history for what would re-appear, transplanted and translated as a result of war, exile, and political repression in the United States and elsewhere later on. It would seem then, that the “homosexual” had its own history, and that this history curiously began in Germany, where a particular people, with a specific identity tied to a certain practice of desire, had come to realize themselves as being distinct, different, and special.13

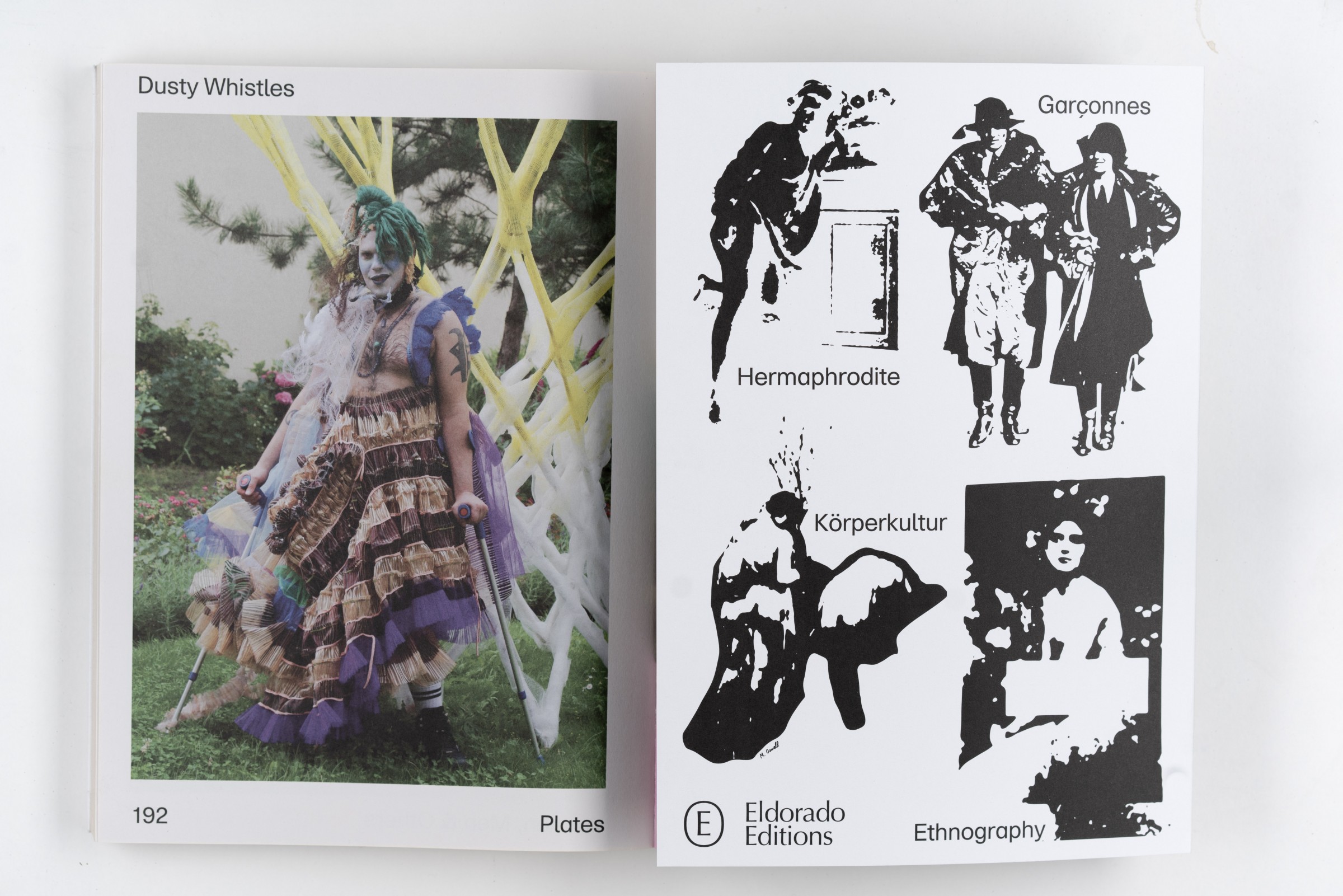

If one were to abide by the requirements of objective, post-Enlightenment science vis-à-vis the study of peoples, obsessed with the classification and categorization of difference as an identity-defining essence – for example, to be found in the normalization of gendered and racial difference – then yes, the homosexual is a type of human, one whose sexual preferences yield a differentiated subject.14 It remains to be questioned, however, where this system for defining different peoples (and by extension, their identities) comes from, and more urgently, against whom this system has been directed to continue modes of oppression – whether in the form of genocidal violence, enslavement, and exploitation, or in the more insidious workings of homogenization, in which difference is tolerated as long as it complies to protocols of (re)presentation and self-control. The naturalization of difference cannot be separated from the history of Nature as a modern category: the European encounter with the indigenous peoples of the Americas necessitated a making-sense of the absolute unknown, a putting-to-work of the natural at the service of expansion and accumulation.15 Eldorado may have referenced a nightclub, but it may have well expanded its scope to include the eponymous Lost City of Gold, one of the many colonial fantasies that fueled early Modern Europe’s race for wealth, power, and territory. Though seemingly unrelated, the history of homosexuality indirectly traces itself back to this primal site of conquest, where “naturepeoples” – their habits and customs, their kinship patterns and affective economies – were simultaneously held in exotic fascination and erotic contempt.16 Two opposing Enlightenment-era political ideologies emerged concerning this state of nature, with contradictory consequences for Modernity: one romanticized the primitive as a site of harmony, liberation, and innocence, while another saw in it an obscene savagery desperately in need of taming.17 In either case, the civilizing process reveals itself as torn between fetishizing and disciplining difference. The spectacle of travelogues, human zoos, freak shows, worldly trade, and cosmopolitan wanderlust hand in hand with forced conversions, slave labor, witch hunts, legal apartheid, medical experiments, and environmental destruction. Notions of sexual and social deviance were developed by the colonial apparatus to come to terms with those nonproductive attitudes and desires that refused to comply with early capitalism’s need for mobilizing bodies to work. This was paired with a transformation in concepts of subjectivity, whereby phenomena formerly understood as an action or a quality of appearance were now seen as essential attributes of Being – thus, not long after the invention of “race” as a natural order, “homosexuality” as a form of life appeared in established scientific discourse.18

In a fitting coincidence, the exhibition Eldorado deployed strategies for displaying the homosexual that bore an uncanny resemblance to formats developed over the course of European colonialism to display non-Western and/or non-Modern peoples. Throughout the 1984 exhibition, itself divided into male and female sections, the visitor would encounter theatrically re-created atmospheres of homosexual environments. The gay boudoir, the lesbian café, the cruising area of the Tiergarten – three symbolic stagings, developed for the exhibition, acted as sets for a range of materials objects, representative images, and informative documents pertaining to these sites of homosexual lived experience. Whether intentional or not, these dioramas are not dissimilar to those found in ethnographic or natural history museums (often the two are combined ) – a recreated Polynesian village, the natural habitat of Ice Age megafauna, an Oriental courtyard. If nothing else, this gesture simply reproduces a museological trope for displaying difference; in one form it is concerned with the manners and mores of non-Modern peoples, in another form it is deployed by Modern homosexuals to explain and show to non-homosexuals who they are, how they live, and what they look like. A neo-tribalism, redrawing the lines of clan and kin beyond biological family or cultural specificity – instead, an interpersonal bond that is naturalized through equating desire with being.19

This is, initially, an unsettling juxtaposition; however, with further thought, an important realization emerges. The history of homosexuality cannot be separated from the history of the Other, its construction, articulation, and fragmentation into divided categories based on race, gender, class, sexuality, origin, and its epistemological capture into the official knowledge-forms that maintain these normative separations as such. The politics of visibility that informed the activism of the Eldorado working group (as well as the establishment of the Schwules Museum* by four of its male members as a response to the exhibition’s success) performed an historically-necessary scaling down of perspectives onto a specific subject. This approach can be seen throughout the various identity-based projects of self-articulation within late liberalism, whereby the Other is spoken and shown as discrete entity (woman, black, homosexual, etc.) in order to draw attention to its incorrigible presence. A dose of historical hindsight, however, reveals the politics of visibility as a story of failure: the demand for recognition and rights through self-exposure necessitates a set of compromises with the eye/I that inevitably generates normalization.20

Nevertheless, the full range of associations afforded by a critical rehabilitation of Eldorado make a reparative reading possible, a delayed understanding of what is at stake once epistemic exhaustion is apparent. The exhibition Eldorado, in its timely incorporation of Modernist violence against the Other, set the stage for a “gay museum” to emerge. Seen today, it provides a score for transitioning towards a “queer theater,” where the performativity of knowledge can be deployed against the eye/I to reconnect discrete instances of individualized oppression into a sensual whole – an imaginary their_story, where it is never clear who they are. Eldorado becomes Odarodle, its mirroring, the ‘theater and its double,’ its re-imagination beyond representation.21

To allow these histories to unfold is not a matter of offering another perspective – to inscribe another line onto the compositional grid of the World Picture. It requires a shattering of perspectives altogether, a dismantling of a unified view, and the disavowal of the picture plane as an organizing principle for knowledge. It is to set up a situation where multiple temporalities of othering can take up space and proliferate alongside one another, unsynchronized and discordant, unresolved and complex, not easy to grasp nor immediate in their relations.22 Odarodle is neither a cry for inclusion nor an ignorance of domination. It is a celebration of existences without giving them a name, knowing the unwieldy magic inherent in naming. It is an opaque gesture, unwilling to lie and say, “here is something for everyone, everyone is welcome.” It is an attempt to learn from past failures, to not give it all away to the eye/I, to keep what is important for oneself, to show difference as an unbridgeable reminder rather than an accessible explication. A natural mystery – a secret known only to some, never to be shared in its totality lest it be irretrievably stolen.23